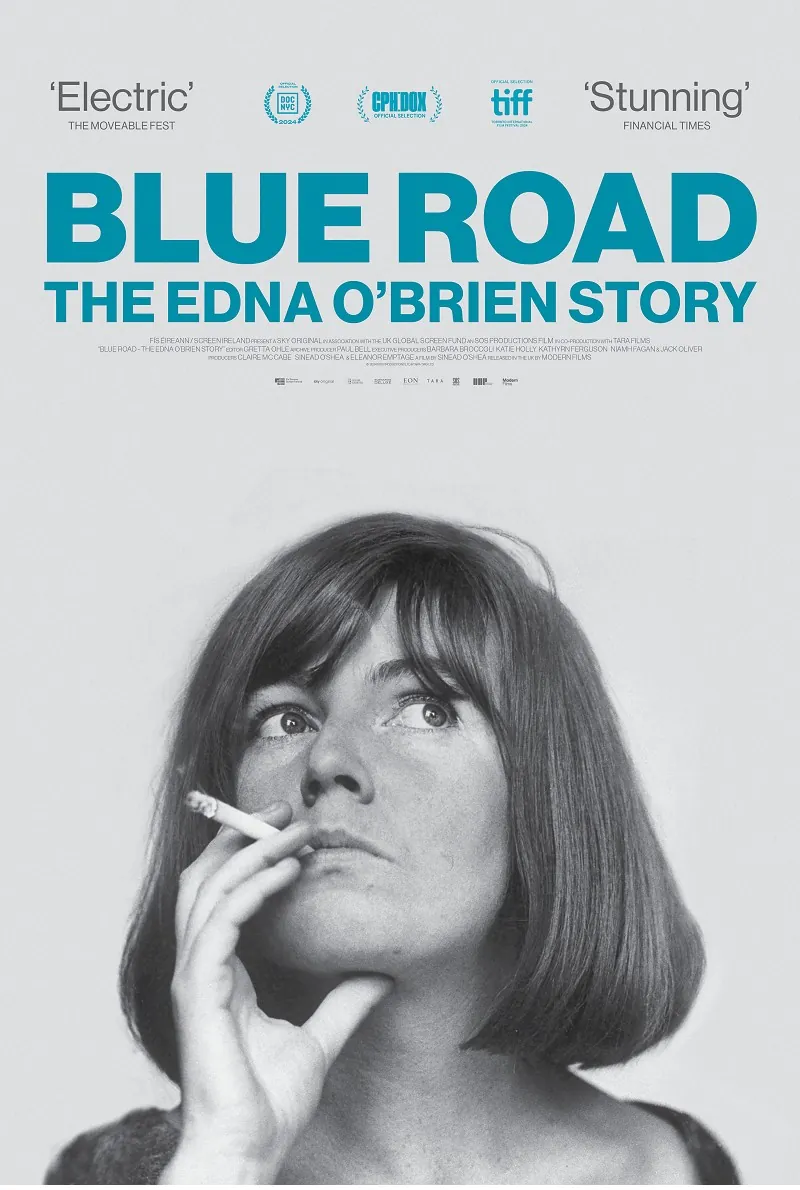

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Blue Road: The Edna O'Brien Story (2024) Film Review

Blue Road: The Edna O'Brien Story

Reviewed by: Anne-Katrin Titze

In 1986, Edna O’Brien published a collection of Irish folk and fairy stories, titled Tales For The Telling. The Leprechaun begins like this: “Bridget was sent out as usual to fetch a bucket of water but when she got to the well near the house she found it had dried up so she had to go across some fields to another well that was near an old disused monastery.” Sinéad O’Shea’s exquisite Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story (opening night selection of the 15th edition of DOC NYC) traces the many paths taken by O’Brien, past the dried up wells, the many Leprechaun encounters on the road, to her ancestral resting place on an island in a lake near a monastery.

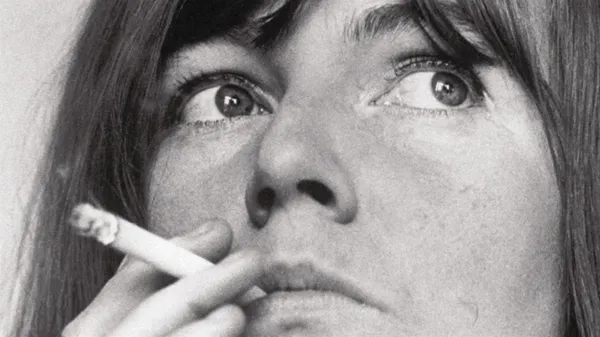

From her childhood in rural Ireland, to training in a chemist shop in Dublin, a scandalous love, a marriage overtaken by poisonous envy, two magnificent children, a writing career unlike any other, a salon in London with guests including everyone from Princess Margaret to Harold Pinter, from Sean Connery to Judy Garland - an overflowing life is presented to us through archival interviews and film clips, and most revealingly through on-camera insights from O’Brien herself, who was then in her 90s, only a few months before her death in July 2024. We hear Jesse Buckley read from the author’s diaries, another treasure trove that may alter perceptions.

“I was born with this ability and demon to write,” O’Brien comments early on in her career, “I was punished for it constantly.” TV talkshow host Charlie Rose introduces her as a “bonne vivante,”on his program, and Gabriel Byrne, interviewed extensively on camera for the documentary, calls her a “famous party giver.” “I’m two people, if not to say 22 people” she says about herself. Her mother recounts that little Edna felt she wanted to change places with a cow, and her sons elaborate on the torturous relationship she had with their father, Ernest Gébler.

Blue Road is packed with revelations about the mores of times and places that go far beyond its subject’s life. Smartly, we are lured in with the glitz and glamour and scandal Edna O’Brien was admired and scorned for. Her son Sasha recalls Paul McCartney sitting at the edge of his childhood bed for an impromptu serenade. There was Shirley MacLaine doing a hand reading to explore Edna’s former lives. Marianne Faithful, Roger Vadim, Jane Fonda - “we were all en route heading for other places,” O’Brien wrote. They were all transitory, “orbiting up, up.”

Her childhood in 1930s Ireland, as the daughter of a man who lost almost all the family’s inheritance and was prone to drinking and violence, made her seek refuge in nature. “Duck seed flying around,” she was always talking to herself or inanimate objects, trees and stones. “The words ran away with me.” Her mother at first did not want her, then wanted her desperately. She was “starving for life” and Dublin from the outside appeared “like a fairy-tale city.” While we hear how young Edna was hoping to meet poets in the capital and be admitted in their midst while writing a newspaper column for women under the name of Sabiola, O’Shea shows us the plaques on Oscar Wilde’s house and George Bernard Shaw’s birthplace, a reminder of the many male gods of Irish literature.

Maybe not surprisingly, the two probably most important, devastating, and impactful loves of O’Brien’s life began with conversations about shared admiration of another writer. James Joyce in the case of her husband to be, Ernest Gébler, and Brendan Behan for her married lover, a member of the House of Commons, only known as Lochinvar.

Ernest Gébler represented worldliness to her. He was 40, she in her early twenties. He referred to Joyce’s Leopold Bloom as “Poldi,” spoke of his trips to Hollywood. His documentary novel about the voyage of the Mayflower had been turned into the movie The Plymouth Adventure, starring Spencer Tracy. Half-jokingly, so we hear, he referred to her as his “child bride” from the start. After her parents received an anonymous letter, the two eloped to the Isle of Man to a house owned by a friend of Ernest’s. The next part of the story, recounted by O’Brien in her novel The Lonely Girl, which was in 1964 turned into the film Girl with the Green Eyes (starring Peter Finch and Rita Tushingham, screenplay by O’Brien herself), unfolds as in a nightmare.

O’Shea’s documentary fills in the blanks: A strange policeman knocks at the cottage door and outside the gate a group of people await her: “My father, an abbot from a Cisterian monastery, my sister’s boss who hired me to write the Sabiola column now scotched, a neighbor of ours and my brother.” The abbot wields a golden crucifix, there is talk of an abortion in England. Edna stays, her boats burned, as a private plane takes away all the figures of authority from her recent past.

Only to be replaced by a new and even more insidious one. Ernest and Edna get married and have two sons. Both of them, Carlo and Sasha speak on camera for the film. O’Shea, who was given access to Edna O’Brien’s diaries has a surprise for them (and us) in store. While Edna’s writing was blossoming, Ernest’s was not. His envy and rage found its way into HER diaries, commenting on the margins, contradicting with icy calculations what she conveyed.

She refused to be destroyed by all manner of violent acts, mainly committed by men against her. Be it fueled by alcohol and a gambling addiction and armed with a gun in the case of her father, or a stranglehold around her neck, a venomous pen, and the disfigurement of her perceptions by her husband, she prevailed in her writing.

In 1950s London, a park across from their house, she wrote each day. Her first novel, The Country Girls, was published and we hear O’Brien explain how she split herself into the two protagonists. Religion haunted her. “I believed Christ walked on water,” she says and recalls how the Virgin Mary stepped out of the painting in her childhood bedroom (which she shared with her mother), to advise her to “keep good, keep good.”

The reaction to her novel in Ireland was as expected. An outrage “worse than Lolita,” with neighbors suggesting to her parents that she should be “driven naked through town, stoning would be next.” The book was banned, while in America she was lauded by the likes of John Updike, JD Salinger, Philip Roth, and Henry Miller. When on July 8,1960 a story of hers was accepted by The New Yorker, Edna knew by her husband’s rage how extraordinary an achievement that was. The camera shows his scribblings in her diary: “Good writing, Ernie, who wrote it for her.” She had to hand over all royalty checks to him and received a small amount for housekeeping.

The misogyny surrounding her takes your breath away. Besides a husband stealing her awareness and undermining her at every turn, there was the hostile male press. A condescending TV interviewer calls her “authoress” and surmises that her own success counters the inequalities she exposes in her writing. In a scenario resembling Nora’s flight at the end of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, a bitter divorce battle leads into a happier, freer chapter in her life.

At 10, Carlyle Square, her new home, hard work writing is balanced with the illustrious parties Edna will soon be known for. Robert Mitchum makes her swoon as he sings her favorite songs to her. Leslie Caron wants to buy the rights to her novel, August is a Wicked Month, and seats her next to Marlon Brando at a party. “He decided that he would take me home and to my dismay dismissed the chauffeur,” she writes about the evening, which continues in her kitchen where “he drank milk and I drank wine.” There was also a rejected Richard Burton reciting Shakespeare, and constant attacks diminishing her in the press. The whirlwind continues. As a patient of RD Laing she takes LSD and lives through many lives in one day.

One of the documentary’s most remarkable sequences begins with an archival clip that shows Edna visiting her family home. “She was always very cute as a little girl and would ask you a lot of questions” says her father. “She was a quiet child, a rather sad person, I would think” says the mother, who recounts her little daughter wanting to swap places with a cow, because cows “are so happy and have nothing to trouble them.” The father smirking at his wife then launches into the song Oh Danny Boy. Next, we see the filmmaker showing this clip to Edna in her nineties on a laptop. She is stunned and has to be reminded that she is looking at her younger self sitting by a window. “He has a beautiful voice and I look quite sad there,” she says, “I look worried and terrified.” More trauma is revealed, as memories seem to flood back to her.

Lochinvar, O’Brien’s unnamed, married lover dominates the next chapter of her life and for years makes it impossible for her to write. While living in New York in the late Eighties, she teaches at City College and Walter Mosley, one of her students, describes her immense impact on him and explains her teaching method of reading students’ work back to the class out loud. “You would see things you would never have been able to see before.”

What looks like footage shot at O’Brien’s apartment at the time of the prior-to-last interview functions as little visual flashbacks to the just heard. There is an orchid in the window longing for light, a walker glimpsed through a door half ajar, a note in her handwriting taped to a door to please leave deliveries on steps, signed with her full name, a framed photograph of Beckett in a windowless room with cookie tins above a display of greeting cards, a Marcel Proust biography with a Harrods slip as bookmark, a book on her nemesis, the Archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid, a book on LSD, and a Giacometti-like dog painting on the wall.

From the troubles in Northern Ireland to Srebrenica, Edna O’Brien’s writing did not lose its grip. On the contrary, her final books explored topics of political conflict and war she had not touched upon in earlier works, without ever losing sight of the the private, casual, lethal injustices she had always so poignantly exposed.

Sinéad O’Shea could not have chosen a more fitting title for her documentary. “It was a country road tarred very blue and in the summer we used to walk there.” This was the first sentence of a short story she wrote. Her husband at the time, Ernest, erupted in anger and scolded her that no such thing as a blue road existed. She knew she was right and in secret clung to the blue road.

Reviewed on: 14 Apr 2025