|

| Sinéad O’Shea, director of Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story: “She was so determined to have her final testimony, to have that kind of final say.” |

Sinéad O’Shea’s exquisite Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story (opening night selection of the 15th edition of DOC NYC) traces the many paths taken by O’Brien, past the dried up wells, the many Leprechaun encounters on the road, to her ancestral resting place on an island in a lake near a monastery.

From her childhood in rural Ireland, to training in a chemist shop in Dublin, a scandalous love, a marriage overtaken by poisonous envy, two magnificent children, a writing career unlike any other, a salon in London with guests including everyone from Princess Margaret to Harold Pinter, from Sean Connery to Judy Garland, from Robert Mitchum to Paul McCartney - an overflowing life is presented to us through archival interviews and film clips, and most revealingly through on-camera insights from O’Brien, then in her 90s, only a few months before her death in July 2024. Jesse Buckley reads from the author’s diaries, another treasure trove that may alter perceptions.

|

| Sinéad O’Shea with Anne-Katrin Titze on Edna O’Brien: “True to say, she has this aspect to her personality, which is a “bonne vivante.”” |

One of the documentary’s most remarkable sequences begins with an archival clip that shows Edna visiting her family home. “She was always very cute as a little girl and would ask you a lot of questions” says her father. “She was a quiet child, a rather sad person, I would think” says the mother, who recounts her little daughter wanting to swap places with a cow, because cows “are so happy and have nothing to trouble them.” The father smirking at his wife then launches into the song Oh Danny Boy. Next, we see the filmmaker showing this clip to Edna in her 90s on a laptop. She is stunned and has to be reminded that she is looking at her younger self sitting by a window. “He has a beautiful voice and I look quite sad there,” she says “I look worried and terrified.” More trauma is revealed, as memories seem to flood back to her.

In 1986, Edna O’Brien had published a collection of Irish folk and fairy stories, titled Tales for the Telling. The Leprechaun begins like this: “Bridget was sent out as usual to fetch a bucket of water but when she got to the well near the house she found it had dried up so she had to go across some fields to another well that was near an old disused monastery…”

From New York City, the day before the DOC NYC opening night screening of Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story, Sinéad O’Shea joined me for an in-depth conversation on her documentary.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Hello!

Sinéad O’Shea: Hi! Oh good! That was so disturbing. My whole computer was just crashing. Oh, dear, how are you?

AKT: I am very well. How are you? Are you in New York?

SOS: Yeah, I just arrived very late last night. So I'm kind of running around a bit. I have to weirdly go to Massachusetts to do some filming later today, and then come back to Manhattan tomorrow for the opening night of DOC NYC.

AKT: You are filming in Massachusetts for another project?

|

| Edna O'Brien's sons Carlo and Sasha |

SOS: Yeah, exactly. It's kind of a key moment in it. So, you know, I was here, anyway. So I had to just do it, but it's really inconvenient. Now, I'm just deeply regretting it.

AKT: Let's talk about Blue Road. First of all, the title. It is beautiful that you use that title, because it's a nod to her. It's a confirmation of her perceptions that she had to fight so hard for. Did you always know that this would be the title?

SOS: No, no! Actually I read that story, and I thought, oh, that's a great story. She tells it in her memoir. Then it's gone through loads of title ideas. But then, about six months ago, I was talking about it to the editor and the editor was like, I really love that Blue Road. Anyway, we basically worked out between us that blue road is Edna's version. And it doesn't really matter if a road can be blue or not, but she is entitled to say it looks blue. It is blue to her and it does represent her breaking free of those kinds of ideas that were constantly forced upon her.

AKT: I think many people, women especially, can identify with that. Your perceptions are taken away from you.

SOS: Exactly, exactly, like Ernest limits her all the time. It's very interesting, I mean, he truly does trick her and gaslight her quite a lot, but he's quite obsessed when you read his diaries, her diaries very early on. You know he's writing in the margins. He's very obsessed with this idea that she's going to get lost to the world of celebrity, that she's ruthlessly ambitious, that she's a narcissist. All these things, but actually none of those ideas correspond with what's actually happening in her life at the time. She's a suburban housewife who's just trying to get her first book off the ground, but he's obsessed with this shallowness that he perceives in her. But there's actually very little that's shallow about her then.

|

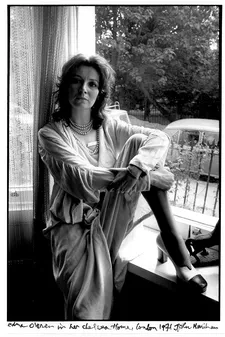

| Edna O'Brien, Chelsea, London 1971 |

AKT: The mere idea of the husband's notes written in her diaries is so violent! It is such an intrusion. There's a moment in the film when you confront one of the sons with it and he seems to have had no idea about the notes. How did that all come about? Did she give you her diaries to look at?

SOS: It's very interesting, I must say I salute her so much for her trust in me, because she really didn't know me. I don't think she has ever really known me properly but I think she was so determined to have her final testimony, to have that kind of final say. We had done one interview together and I'd shown her a piece of video archive. You know, that piece of video archive later in the film where her family are being interviewed by a television company. It's in the mid 1970s and her dad sings Danny Boy, and she's sort of frozen in horror and anxiety. And the whole thing is a total pantomime. This is not a happy family. This is not, you know, a sweet Irish scene. This is really ...

AKT: Cold.

SOS: And everyone's lying! The mother's lying about, you know, her books never worried me. It's a total lie. Her mother buried her books, and the dad is pretending to be really kind of jovial, and so Edna's face bears all that tension. I showed her that piece at the end of our very first interview, and I think she must have felt like I did understand something of her because she wrote to me afterwards, and she said, make sure to include that now in the film. And I was like, don't you worry! And then, she said, I think you need to read my diaries. She has actually three sets of diaries in three different archives around the world. And she said, go to Emory College in Georgia.

That's where the most naked - that was the word - diaries are. I guess she must have known that I would find the diaries with the husband's handwriting over them. And so then, to answer your question about the son, I mean, the son was very aware of the father's personality. He has actually written two books about life with his father. But he didn't know about this and so I had to be quite careful, because I didn't want to ambush him exactly too much.

|

| Sinéad O’Shea on Edna O'Brien: “Edna did feel and was made to feel like an outsider in Dublin's very male literary world. ” |

But at the same time I needed that verification to happen on camera, because otherwise, for the audience it was going to be quite hard to understand. We needed to lay out very clearly: This is the husband. Make no mistake. So it needed to be the son. The son would know his handwriting. But I also wanted to be quite courteous, I suppose, about it as well. So that was a kind of tricky balance to strike.

AKT: It's an incredible moment. The comments are really strong because the combination expresses everything. You understand what this man was doing, the gaslighting, as you say.

SOS: Yeah, you get the dynamic straight away, and you know she's imperfect. I would never suggest she's the ideal mother, the perfect wife, the Renaissance woman. She's really flawed, but there is no doubt that she was enduring a very abusive marriage by a very controlling, very angry, very jealous, insecure man, who gaslit her, and then also gaslit, I feel, the rest of the country. He insisted on telling all his peers in Ireland that he had written her books.

I studied English in university in Ireland and it was a course that's considered to be a very good English literature course, and there was no question that we would study Edna O’Brien. She was always considered to be very frothy, very lightweight. In fact, a classmate of mine, when I told him I was going to do this film, he said, I was always told, growing up, that she hadn't really written her books! And so this was just this really insidious idea of her that was so prevalent in Ireland, especially amongst the polite literary types. She's a bit of a fraud. She's a bit of a chancer. It's such a dreadful thing that he did. It was such a dreadful piece of revenge.

|

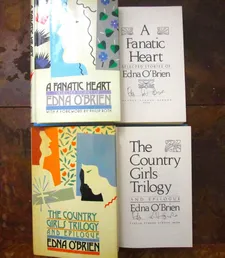

| A Fanatic Heart & The Country Girls Trilogy, signed by Edna O'Brien, collection Ed Bahlman |

AKT: Yes, it is. And you explain so well her wish to be a part of the literary community. The Introducing James Joyce by TS Eliot book that she carried around, going to Dublin and the “fairy tale” of being a part of the literary establishment being so strong and important to her.

SOS: I think even until the day she died she felt both inside and outside of it. There are so many great Irish writers, as you know. There's Edna, there's Anne Enright, there's Eimear McBride. There's now Sally Rooney, but actually the literary tradition in Ireland is male a lot of the time. It has been laid down by Yeats, by Joyce, and so she was outside of that, and she was also the first, which is always a very difficult position to be in, and so she was accepted.

But she was never as accepted as much as she was accepted abroad, in the US, where she's always been taken seriously, as we say in the film. She delivers the eulogy at Philip Roth's funeral. She's been interviewed on very big arts programs, whereas in Ireland she's being sniggered at. That's partly the husband's revenge, but it is also the mindset in Ireland that she just doesn't fulfill the requirements of a literary writer.

AKT: The archival interviews in many documentaries I've seen this year have been very telling. There were a number of documentaries that featured interviews of very prominent women from Liz Taylor to Diane von Furstenberg and here again with Edna O’Brien, the misogyny from the mainly male interviewers is startling, the tone, how they talk to her. Here's the little writer woman! I noticed when you show briefly the Vanity Fair article from ’88, ’89, a little aside, the first sentence mentioning “her breasts abound.”

SOS: We didn't have time to interrogate every single piece of media. But it's very intentionally there, and you should see that phrase, “her breasts abound.” How do breasts abound? It doesn't really even make sense. They're there. They exist.

AKT: That sentence says it all. At the same time her life as the “bonne vivante” in her salon has fascinating stories.

|

| Edna O’Brien to Sinéad O’Shea: “It's actually the women in my life that I've needed most, and they are there for me.” |

SOS: True to say, she has this aspect to her personality, which is a “bonne vivante.” It's very extrovert, very celebratory, very generous. We had our first Irish screening a couple of days ago, and someone stood up and said, I just want to talk about Edna's generosity. I'd go over to her house, and she'd just feed me champagne, and she'd say, this champagne won't give you a hangover. She was always giving her presents. She was generous to a fault. I think she liked the idea of hosting parties. I suppose actually, we need to go a little back in our assessment of that.

I think it's important not to be worried about overstating the poverty that Edna came from. 1930s, Ireland, it was just post independence from England. It was a miserable, difficult place. The government was so dysfunctional. There was an economic war with England, still, they were putting tariffs on all Irish goods. Poverty was everywhere. Though Edna's family did actually live in a much bigger house than most people they had nothing. Her father was an alcoholic. They had absolutely no cash. They had to sell chicken eggs to be able to get food themselves. So I think Edna's horror of poverty was so forged in that background.

And so her response, then, when she got some money, was to be just so wildly extravagant. Throwing these parties, giving people so many drinks and cooking hugely elaborate food for them, it wasn't just a party. It was just this feast that was being put on for people. But I do think it was in response to that poverty and the precarity of her childhood which really can't be overstated. 1930s Ireland, throughout most of the 20th century, it was a very miserable place.

AKT: For the parties and the guests, you must have had difficulty choosing which episodes to feature! Robert Mitchum? Maybe Pinter? So many to choose from!

|

| Tales For The Telling by Edna O'Brien, collection Ed Bahlman |

SOS: Yeah, there were so many. I could have got into way more. I mean, there was John Houston. Yeah, there were just so many celebrity accounts. There's kisses with Ted Hughes in her diaries. She's not that worldly wise about it. Each man she takes very seriously. She's very romantic, very naive and wide-eyed about it, very hopeful that this will be the man who will satisfy her and care for her, and that never happens, never once happens.

AKT: Which brings us to her secret lover Lochinvar. Do you know who it is?

SOS: Yes, I do know. And I didn't put it into the film because his wife is still alive and he's still with her. So I felt I didn't want to hurt his wife. I didn't care so much about him. But he was a very high-profile British politician, and it is quite amazing that it never came to light. And it was a very, very tortured affair. I mean, I think we've all had our share of bad relationships, but this one to me is the most excessive one I've ever witnessed. We include a lot of diary references to account for it in the film, but that is nothing compared to the experience of reading about it in the diaries, because she stops all fiction writing during this phase.

So she's just writing about this love affair in her diaries over years, it's more than six years. There are so many notebooks, so many thousands of pages of Lochinvar, Lochinvar, Lochinvar, and will he call? He came around. He was horrible to me. Silence for a few weeks, and she's going through these phases where she's like, I drink a glass of water, just to distract myself. I put it down. A minute has passed. The rest of the day is still to go. It is awful, it's total obsession and it's so devastating, and it really destroys her for quite a long time. She can't write. She doesn't make any money. She ends up selling her house, she ends up renting. She ultimately tries to commit suicide.

AKT: Destruction. That's the destruction that follows each love. Early on in your film, there's a moment when she mentions that she was always talking to inanimate objects, to trees and stones. I think part of her storytelling begins there.

|

| Inis Cealtra (Holy Island), an island in Lough Derg, where Edna O’Brien is buried |

SOS: There was a lot of thought put into that structure, because there were infinite ways of telling this story, but in the end we decided to tell it chronologically, and we also, I suppose, decided to plant or emphasise certain themes. The themes that we felt were the most important in her life. Others may have different interpretations.

AKT: Walter Mosley is a great get. And he's wonderful describing her way of teaching by reading out loud her students’ work, which is also a smart way of not having to correct it.

SOS: Actually, I think that's very true. I think it was a mixture of both. I would have happily just had the film be my 40-minute interview with Walter, because he was such a wonderful speaker, and he had so many fascinating insights about her and her life in New York, but we had to limit it to that short excerpt. But he was saying to me beyond that, that she wasn't that well liked within the department, because she didn't keep office hours. She didn't see students.

She didn't want to take on a lot of the administrative tasks that are so intrinsic to teaching. But what she did was she gave her full attention to your writing. For him that was all he wanted, and for him it was life-changing. It's such an extraordinary story, and it is this aspect to Edna which people just don't know about.

AKT: Gabriel Byrne makes interesting comments, calling Dublin an incestuous place.

SOS: He's right, and I still think there's some truth in that. Yes, it's very small. I guess it's again hard to exaggerate how small it is, and how watchful! You know, it's quite like a village, and people in token, they pride themselves on their worldliness. But actually, I think it's very like a small village with people constantly commenting and pronouncing upon each other. Yes, I think Edna did feel and was made to feel like an outsider in Dublin's very male literary world. I still think a little of that exists actually.

|

| Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story opened DOC NYC in 2024 Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: The first sound that always comes to mind for me about Dublin, is that at night, there were still horses going up and down the street.

SOS: There's still. You could always hear horses in Dublin, well, particularly where I live, and there are a lot of horses around, and that's kind of in the city center.

AKT: In the center exactly, right outside the hotel. Edna’s father loved horses. She returns to the song Danny Boy when you show her in the hospital. It links to that moment when you first met her.

SOS: I really loved that. I had a sense of that Danny Boy story. She had written about it in a short story. It's a fictionalised version. I knew it must be true. And then I found out later, it was true. It's an amazing story. Her relationship with her father was so complicated. I think in that final interview she's come to an accommodation. But over the course of that final year I spent time when they're doing audio interviews and I went through all her diaries, and I can just really see that there was just so much hurt there. He caused so much pain to her and her mother when she was younger.

AKT: In regards to the theme of fathers, one of the most painful moments in your film is Ernest Gébler’s commentary to his sons. The sign-off from this letter: “From your ex-father.” The cruelty takes your breath away.

SOS: Yeah, it's breathtaking exactly. It's a very good way to describe it. He was an incredibly difficult man, and theirs was an awful marriage, and I think both sons prevailed in their lives, and they're both very sane when you speak to them, very reflective. I think it has been challenging for them at times, but I really admire how they've managed to survive.

AKT: You show so well in your film the monsters she had to face. I mean, she's actually Lochinvar! She's the knight facing the dragons.

SOS: Exactly. She is her own knight. Also very sweet, you know. Part of the process as well of making the film was that she sent a lot of lengthy voice notes via phone to one of our executive producers, and she would pass them on to me, and there's a very sweet voice note from her hospital bed, and she acknowledges, she says, it's actually the women in my life that I've needed most, and they are there for me. And she's right, because women actually gave her far more uncomplicated love.

AKT: Thank you so much for this.

SOS: Thank you! You watched it so beautifully and so attentively. It was very nice to speak with somebody who really engaged with it like that. Thank you.

Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story opens in the UK on Friday, April 18.