|

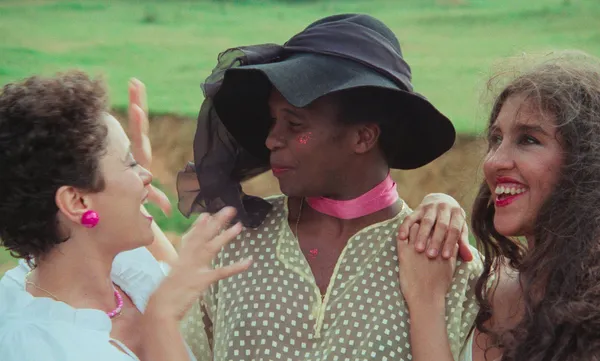

| Onda Nova Photo: BFI Flare |

For the most part, BFI Flare presents brand new films, often as premières. Each year there’s a small number of retrospectives beloved by the community. Onda Nova is something a little different. Originally released in 1983, it was banned in its native Brazil, under the military dictatorship of General João Figueiredo. It’s only now that it’s finally getting a proper release there. I met one of its two directors, Francisco Martins, to find out more.

“The censorship at that time was very institutional,” he tells me. “They were strict, but there were very clear rules. We knew what we could film and what we could not film. Erotic comedies were a very, very popular genre in Brazil. It was very clear, for instance, we could show butts and cheeks, genitals, back nudes, okay. Front nudes only in a large frame. So we shot the film like that. So they had no argument. They could not cut one or another scene, because it was all filmed according to the rules. But what happened?

“It happened that at that time, that genre which was very popular, okay, they had nudes, they had love scenes. But in a way, they were very sexist and very moralistic. Not all, but many of those comedies had a very patriarchal look. Women who were very sexually free, they were more or less compared as prostitutes. Gays were always a bit ridiculous, and so on. Our film had nothing of that and had no moral judgement, so that was why the film was banned here in Brazil. They considered that the whole film was immoral. It couldn't just have one cut. That would not fix it for them.

“Because censorship was an institution, you could have a lawyer discuss proposals, present opinions. It was a kind of judicial negotiation. But what happened? It was that in the space of about six months, we were trying to deal with it, to convince them to liberate it legally. Pornographic films were forbidden in Brazil but they started to be liberated because they would get into the Supreme Court and say it was a matter of freedom of point of view. But it costs a lot of money. Each one of those cases would be almost the price of the budget of our film.

“So those films got liberated in six months, and they invaded the theatrical market in Brazil. And in the first moment, they made lots of money, because it was something people had never seen. So after six months, it became kind of ridiculous for our film to be banned. They had no legal reason at all to continue to ban Onda Nova while the theatrical circuit was full of really pornographic films. So then film was liberated.

“It was actually released almost a year after it was finished. And at that time, the theatrical market in Brazil was completely split. You had pornographic films, or you had films with no sex at all. So that genre of film, erotic comedies, which were called porno chanchadas in Brazil, they disappeared in the space of three, four, five months. So when the film was released, there was no space in the market for it. It was a commercial failure.”

So how does it feel to be re-releasing it now?

“As time passed by, the film became kind of cult,” he explains. “It started to be shown on TV and streaming and also at some festivals. When we started LGBTA, queer festivals, we started to look at the film as a kind of pioneer of a different way of showing homosexual and queer characters with a kind of naturalism. They were real characters, they were dignified, they were considered as regular persons.

“The festivals were only in Brazil at the beginning. Then the film was selected for Locarno. The copies of the film were in a very, very bad state. When the film was selected for Locarno, Julia [Duarte], as the executive producer, she let us make a restoration. She joined again with [the film’s other director] José Antonio Garcia’s family. We were still friends, but very distant friends. José Antonio died in 2005. After he died we lost contact. We met eventually, but it was not collaboration. So Julia joined us together again and we started working.

“When the film went to Locarno, it was very well received, especially by the youth, the youngest teenagers. They loved the film. And then the film was shown again in the São Paulo International Film Festival, and it was a big success. It's A kind of genre of film that there's a long time there was nothing like that in Brazil. So then we had the distributors, they looked for us and said, ‘Well, let's release the film again, because we think thatit will be very good now.’

“In a way, the conditions of Brazil are more or less the same. There's a certain coincidence. When the film was made, it was at the end of the military dictatorship. Well, it was still the military dictatorship, but it was in the end. And here now we are just emerging from a four year long, very dark era of Bolsonaro, which was a revival of that thing. And in a way, Brazil also became much more conservative during that time. I think young kids, they are really looking for the film and enjoying it. If you look at the things they are writing on Instagram and things like that, they are amazed with the film.”

When he was making it, was he just telling a story he wanted to tell, or was he conscious that he was doing something pioneering when it came to presenting queer people?

“It was kind of natural,” he says. “Actually we made a film before the Magic Eye Of Love, which was not so exuberant but had already that kind of look. Because when we started to make that, the producer proposed, ‘Well, let's make an erotic comedy. Then you’ll get the money and then make another film.’ We said ‘Okay, we're going to make the film, we have nothing against filming erotic love scenes. But we will not do it in a moralistic way as it was usually done. So that was already a difference.”

We talk about the costumes in the Onda Nova.

Speaker 3: 13:35 “The main actress [Cristina Mutarelli], who plays Lili, the goalkeeper, she's the art director,” he says. “It was the beginning of the new wave movement in Brazil. So that look was already around town.”

Then there are the sex scenes, which feature plenty of nudity but don’t look like pornography. The focus is on character rather than mechanics.

“That's one thing we were proud of,” he says, “because it's a question of showing it, but not in a vulgar way, I think. Well, in the history of art there have always been erotic scenes, since Pompeii and before that, so it's a tradition. What is interested us was to show the liberty of people, the beautifulness of the bodies and show it in a natural way, not in a vulgar or sensationalist way. Me and José Antonio, we grew up during the sex revolution of the Sixties and Seventies, so the film is more or less like we were.”

The film is also historically interesting because it’s centred around a women's football team, and that was a new thing at the time – for the preceding 40 years, women had not been allowed to play.

“In that way the football team is a symbolic thing,” he says. “When that changed, though it was no longer forbidden, it started a big discussion. ‘Well, it's a sport. It’s not for women! It's not for girls!’” He laughs, pointing out that in the US it’s seen as a girls’ sport. “So there was a big discussion and then they were discussing how they would regulate it to make a league, to make tournaments, things like that. It was a public discussion about how to regulate it.”

That was what prompted him and José Antonio to begin work on the film, he says.

“In Brazil it would be very symbolic because it's a very patriarchal society and football is considered the national sport. At the same time it's a very popular thing. People do not play only for winning. Well, now it's become much more a business, but not everybody thinks about being a professional player. People play because it's good. So I think it was very symbolic that women were playing. And we had a big problem because the main actors, they didn't play football at all.”

The presence of strong-willed female characters was always going to create an issue for the film, he says, even without the sex.

“It's a different point of view. And especially for them at that moment, and even now, after Bolsonaro government, it was just like that. Women were completely objectified.

“Our first film had already shown women take the initiative. They are the main characters, they are the protagonists. And actually in all films we've made, even the film José Antonio made after that, when we were not working together anymore. And also a documentary I made about the Brazilian sculptors [Maria: Não Esqueça Que Eu Venho Dos Trópicos], the protagonist is female. I don't know why, but it's something we realised after we had made them.”

Producer Julia Duarte is present and has something to add at this point: “What was transgressive? It was not the sex, because the sex was really how the production was done in Brazil at that moment. Everybody was consuming these kind of films. But normally in the porno chanchado has, the women were always submissive, or really perverted, or they were corrupt saints that was suffered, or they were prostitutes. And then if there was a gay character it was in a negative way. So the sex was normal. The non-normal part was the progressive part, like giving a voice to women.”

We discuss the financial challenges of making the film.

“It was a very low budget,” says Francisco. “We wrote the film for the budget we had. That it was how it was done. Well, it will be five weeks shooting, so many characters, so many locations. But the first one we did was The Magic Eye Of Love. It was done in three weeks, three locations, two main characters. That was it. And then there were some additional characters, but supporting characters. But that one [Onda Nova], it was supposed to be five weeks, but it was shot in six. We exploded our budget because of the football scenes. They were very hard to shoot because girls didn't play. It's funny to think how things changed in 40 years. Brazilian female football now is already professional.”

He’s very excited about screening the film at Flare, as is Julia, who explains that it’s part of a much larger restoration project.

“We have this project of restoring all the films [by José Antonio Garcia]. It's called Cinema of Desire. There are three also by Francisco, and then Última Copa by just José Antonio. We think the BFI is a great spot, and Flare is one of the most important festivals for queer cinema. We're super happy and excited, both of us. We really felt that they really liked the film, and it was super beautiful what they said about the film. We felt a lot of caring and nice vibes from the team.”

Francisco nods. “One thing which is important about that project is when we started thinking about restoring the film, and then Julia came with this project idea and we were looking for the name, we started to see what my and José Antonio’s films have in common. They have in common the desire. They are all films where desire is what makes the plot go and what motivates the characters. Because desire is always an affirmation of life. So that's why it's called Cinema of Desire.”