|

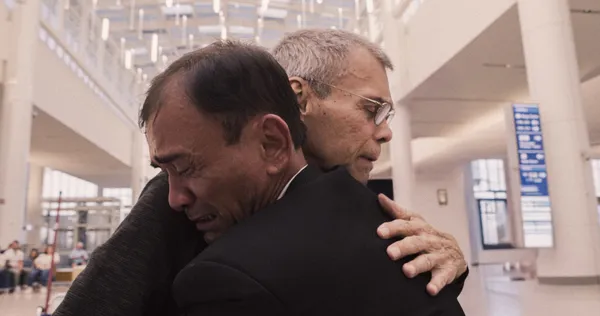

| Sang and Nelson in Child of Dust. Weronika Mliczewska describes her approach, saying: 'I never wanted to judge anyone' |

With her feature film debut Child Of Dust, Polish director Weronika Mliczewska follows Vietnamese Amerasian Sang Ngô Thanh as he attempts to make contact with his American father Nelson Torres and his family. Sang is one of the hundreds of thousands of children who were born to Vietnamese mothers and US servicemen during the Vietnamese War and who have faced a lifetime of prejudice in their homeland – where the father is seen as vital – as a consequence. The subject is an emotional one and Mliczewska follows it in intimate fashion as Sang faces a series of difficult choices if he is to finally meet the father he has never known. The film received a special mention after its premiere in competition at Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival, where we caught up with Mliczewska to talk about tackling the subject and the difficulties of shooting in multiple countries. She began by telling us how having an outsider viewpoint helped.

Weronika Mliczewska: I think my nationality helps in a sense because I have a background of extensive travelling. I studied anthropology and filmmaking at Goldsmiths in London. I also studied at Warsaw University and I studied postgrad in LA.

I was talking to the Vietnamese producer Chi-Minh de Leo, who has been with us since day one, and he said that it is actually good that a person from outside is tackling this story because in Vietnam, for Amerasian people, they’re still kind of taboo and there might be issues with censorship and complications for a director from Vietnam. He and his crew from Clubhouse were always with me translating cultural differences and making sure that I tell this story from the point of view of the Amerasian person.

How willing was Sang to get on board and be followed because it’s a brave decision as it’s a very emotional journey for him right from the outset?

WM: For him and for the American family, it’s also very brave. I didn’t know where we were going to get with this story, so I didn’t know if the family on the other side would accept the filming process so it was always a challenge. For him, I think his emotions were so overflowing that the fact that we were following him with a camera allowed him to express himself. I think this did him good because he felt like he was noticed and his voice was heard.

In a sense it wasn't like we were taking something away from him. It was more like we were giving him the acknowledgement finally. He was searching for acceptance, belonging. He was always scrutinised and on the outskirts of society and this is his way back. So I think we empowered him and we were witnessing his way back but he's such a strong character himself.

How was working with Sang’s American family because, in a way, they not only accepted him but accepted you as part of that. How was convincing them to join the project?

WM: For us the pandemic helped because we had a lot of time to build trust with the father and the oldest brother and they had a lot of time to process the whole situation. So for almost over a year, we were on the phone calls, we gave them space and time but we were always honest and transparent about what this film was about. At the end of the day, they really believed in our motivation and they wanted to kind of set an example for other fathers and other families to take the responsibility. They did, in a beautiful way. Of course, not everyone is perfect but that's the beauty of this film as well. That we don't land in the perfect family and the question is which family is perfect?

Were you aware of the split in the family that becomes apparent during filming?

In the very beginning we were just going into the arms of, ‘let’s hug at the airport’ and everything’s going to be perfect. With time we started also discovering that the family is, in a sense, a difficult family. I never wanted to judge anyone because we never know, for example, what the extent of the impact of war is on the father.

It’s interesting that you’re coming to this story so many years after the event because a lot of people will be familiar with the idea of the ‘children of dust’ because of Miss Saigon, but now decades have passed.

WM: I was always making the connection with Miss Saigon and, actually, not many people react to it. Maybe in England, Scotland you know maybe it is more present because of the show.

What surprised me was that he was only just doing this now. But perhaps it had only just become possible?

WM: Yes, it had, because Sang, our character, had done the DNA test before, but it was just by pure coincidence that his half-brother found the DNA test on sale, and he did it. And this is why the match only happened in 2019.

There are beautiful scenes with him and his grandson and his wife, who is remarkable.

WM: Yes, it's a sacrifice in a sense, with full-on support. Just as a backstory, it’s a really beautiful love between her and Sang. She was working as a policewoman for the regime and because she fell in love with Sang, who is Amerasian, she lost her job and they started being difficult with her. She couldn’t find another job because she is with the child of an American Soldier. So she kind of sacrificed her career for this love, that's really beautiful. But it also shows how difficult it is for people and how much he got being a descendant of the American person. He could never get a good job, he was always shunned by society.

Were you ever concerned from an ethical perspective in terms of what he was going through and the choices he was having to make?

WM: I was concerned for him all the time. I was even asking, do you really want to go? But that was his dream. He was always so sure that he wanted to be there. He never wanted to be there for the US, for the American Dream, he wanted to be there to meet and take care of his father, to hug him, to be acknowledged, because the father in Vietnam means everything for a person, for your identity. But I think he never thought about it long term, what's gonna happen after you hug your father, after you meet him?

|

| Sang with his wife and grandson. Weronika Mliczewska on the couple: 'It’s a really beautiful love between her and Sang' |

This is where the cultural clashes come in because, at the end of the day, they've never known each other before but they're trying. I was worried for him so many times but I was there to witness his story. Many times in this film, it was a case of how much do I help him, how much do I follow him? But I guess we set up a nice relationship. I think, many times, because we were filming him, it was also easier for him to be noticed and be taken care of. Of course we helped him too, just with basic stuff but not with the main decisions, I would never want to be responsible for that because it's his life.

In terms of shooting it, did you have a team in Vietnam? I imagine it was tricky because of the pandemic?

Yes, because of the pandemic, we could go because borders were closed. We had our second team in Vietnam and that's amazing because the pandemic really helped with the technology. Vietnam closed off from the whole world for two years but the industry didn't shut down. Our co-producer was shooting remotely and they were shooting mostly commercials as well with foreign directors. So they had this system of Qtake [a video assist system]. How it worked was I would be in Poland and they would be shooting there. I had my assistant director who would be speaking in Vietnamese with Sang and then I could see exactly what was shot on my tablet. We did this in situations that were very necessary, not to miss the moments. We needed to find ways to be there.

Sang didn’t see the whole film yet, he keeps breaking into tears. From an ethical point of view, I want him to see the film once with his family but I don’t want him to have to live through it over and over again because it’s also very emotional for him.

He has spent his whole life feeling torn.

WM: In a sense this film is not only about Amerasians, it’s about everyone. We belong to what we love and who we love and it's about people rather than borders and politics. And I hope this could be the message of this film.

You do keep the politics out of it, although there is some archive footage to remind us that Sang is one of hundreds of thousands. How did you choose that specific footage given that there is quite a lot from that period?

WM: We were thinking, do we use the iconic shots that everyone will relate to? I went for a more emotional path. Of course, the helicopters from the Vietnam War are pretty iconic in their own but the first image of the film is the helicopter and then panning down to a child. Our film is like that, we are showing the human face of the war. We are not going into the politics but, at the same time, I am very critical of the American presence in Vietnam and how it all ended. There are no winners in a war and we’re showing it.

Were you ever concerned you might have to stop filming?

|

| Child of Dust Poster |

WM: Yes, first of all during the process the father got sick. That was a turning point for Sang of, “I’m going right now” because he really wanted to not to miss his chance to meet his father. That was one thing and, of course, when you are following one family, at some point, they are like, “Oh, we thought it's going take three weeks and that's it. Then after four or five years, you're still there.” We are like a family. There were occasions when they were quarrelling between themselves and they were calling me. I felt like I could be a psychologist.

That's a lot of pressure for you as well because you know on the one hand you want to help but on the other you want to keep a distance.

WM: I cannot keep a distance. It’s one of those films where you can’t be impartial. It's been intense and for me as well, personally, because you are asking if I wasI wondering if we will finish the film. So in the middle of the process, I found out I was pregnant. Firstly, I was happy about it but my second thought was how will I finish this film? So luckily I could. It was a little bit stressful but thanks to the support of my closest ones, it was possible. That's also my message to all female directors. You can have kids and keep on making films. It's possible!