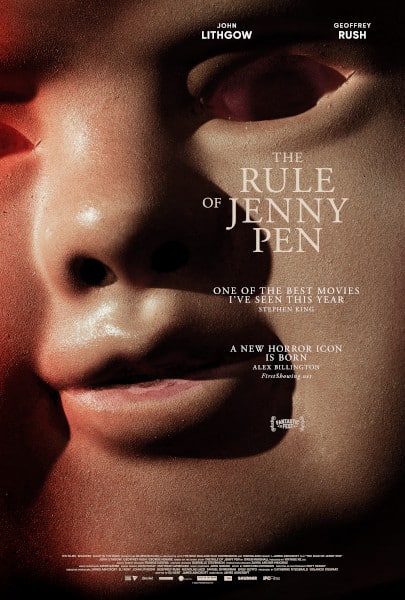

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Rule Of Jenny Pen (2024) Film Review

The Rule Of Jenny Pen

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The conversations that we have as a society about care homes are peculiar. They always seem to revolve around what we would like for our parents, and not what we might need for ourselves. This distancing extends to their invisibility in the realm of fiction – they’re just not a part of the stories we share, or at least not with residents as protagonists. The Rule Of Jenny Pen is an odd blend of drama and horror, with aspects of the Gothic, which doesn’t always succeed in its aims, but which is important in light of its willingness to explore this territory.

The story revolves around Stefan Mortensen (Geoffrey Rush), a strict, irascible judge whom we first see very deliberately crushing an insect as it crawls across his desk. His harsh words for a mother who tries to thank him for sentencing the man who abused her children might make viewers unsympathetic to him, but it’s difficult to know how much of this is an expression of his true feelings and how much it’s distorted by something going wrong with his brain as, moments later, he collapses, afflicted by a stroke. We catch up with him later in a care home where he is being examined. It’s a sudden, overwhelming introduction to a new phase of life.

Like many an intelligent, professional person in such circumstances. Mortensen tries to reassure himself that this is a temporary state of affairs. He can’t countenance the idea that he might have to share a bedroom for the rest of his life, or live with practically nobody capable of intellectually satisfying conversation. His own resentful attitude is a barrier to engagement at first, but many of his fellow residents seem barely conscious, whilst others talk coherently at first only for it to become apparent that they’re delusional or suffering from severe cognitive impairments. He doesn’t seem to consider talking to the staff, perhaps because they’re frantically busy, perhaps because their role – and potentially their gender – leads him to think of them as inferior. Soon, however, he will have bigger problems to contend with than simple frustration and loneliness.

Many nurses hate working on stroke and dementia wards. That’s not because they lack sympathy for the patients; rather it’s because some of those patients, mostly men, persistently abuse others. Doctors put it down to impaired inhibition but those at the sharp end think it’s more often an excuse. Mortensen’s new home has its resident abuser, as he’s quick to find out, though this one is smart enough not to mess with the staff. His name is Dave Crealy (played by John Lithgow), and he slips in an out of others’ rooms at night, violently assaulting them, forcing them to submit to his therapy doll, the titular Jenny Pen. He’s been tormenting Mortensen’s roommate, Tony (George Henare) for a long time, and nobody dares to oppose him.

What is a man of the law to do when he finds himself living in a world where he has lost his authority and no amount of reason or use of official channels can prevail? He’s still smart, and determined to outfox his opponent, but the unstructured nature of his social environment is paralleled by a breakdown in the structures of his own brain. Like many people recovering from strokes, he remains fragile, experiencing mini absences which result in him seeming to skip forward in time with no idea what has been happening around him. In one deeply disturbing sequence he appears to see a man burn to death in front of him, but nobody else ever references this incident. Did it really happen? The only other witness was a tortoiseshell cat who continues to watch him warily, as if it knows something he doesn’t, or as if it alone can move freely between what seem like two different planes of existence.

Whilst the uncertainty created by these experiences sometimes makes the film hard to follow, and it isn’t always tight enough to get away with that, it’s interesting material for a thriller. This is not a game played for petty stakes; with many people in the home extremely vulnerable, Dave is a real threat to life and limb. Director James Ashcroft gives viewers something of a sense of how helpless people can feel when their physical strength or mental capacity has diminished. This isn’t as acute as it might be because we are seeing events from the perspective of a man who has yet to fully recognise himself as disabled, but that journey of understanding also contributes something to the experience.

Adapted from the short story by Owen Marshall (who can briefly be glimpsed in the courtroom scene), the slight (though twisty) central story is fleshed out by committed performances, with Rush’s willingness to appear naked in a deteriorated state a reminder of how easily disabled people are stripped of their dignity, especially in environments like this, their bodies becoming objects without meaning. At the same time, Ashcroft’s interpretation steers the story away from simple tragedy as we see Mortensen making gains as well as losses, his own habitual, defensive cruelty falling away from him as he is reminded of the value of humanity. Immersion in community and forced engagement with his own dependence offers a different flavour of rehabilitation. When all is said and done, one way or another, there will be one less monster in the world.

The Rule Of Jenny Pen will be in UK cinemas from 14 March

Reviewed on: 03 Mar 2025