Eye For Film >> Movies >> Nezouh (2022) Film Review

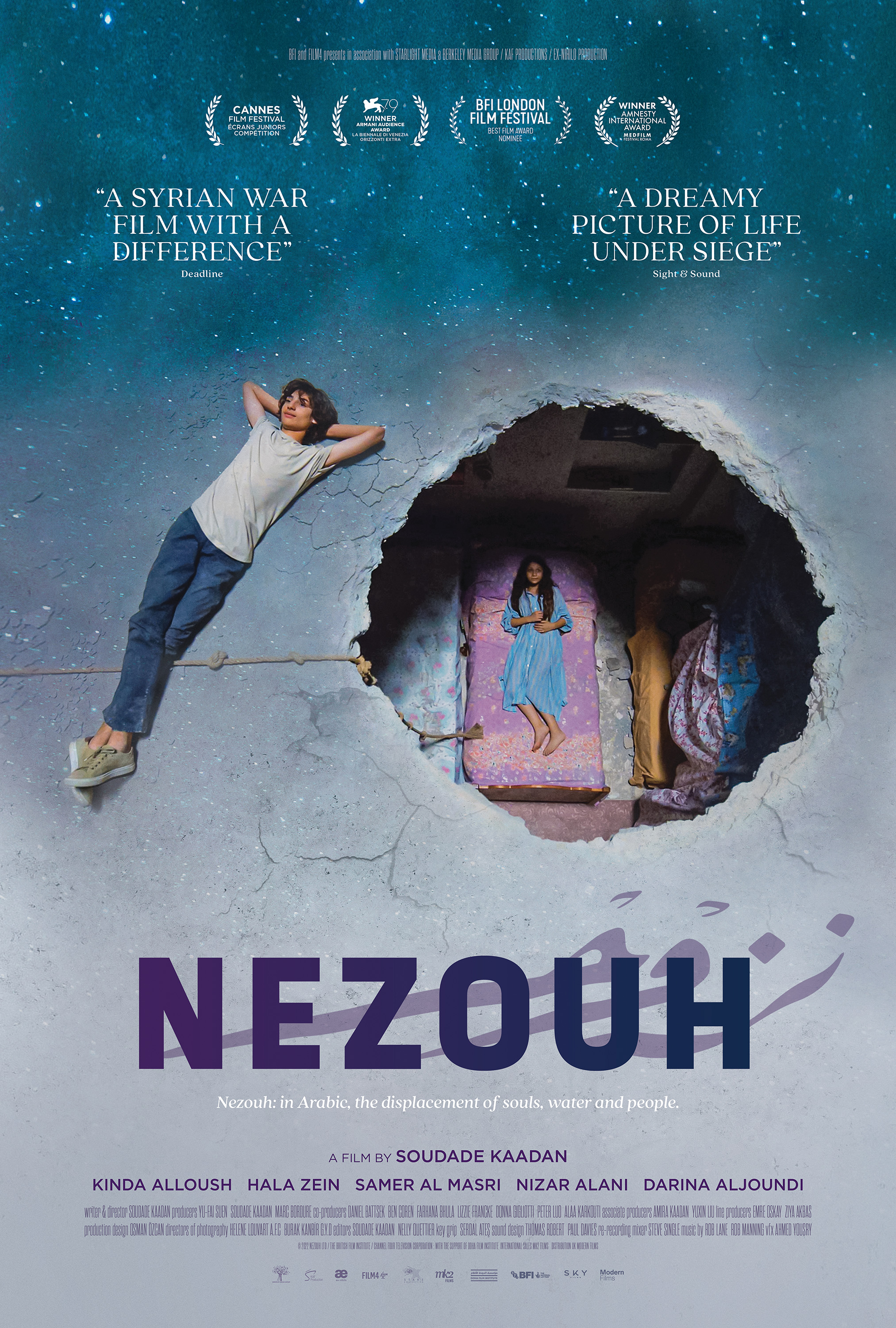

Nezouh

Reviewed by: Amber Wilkinson

A city under siege in the throes of war becomes the setting for a tale of unexpected liberation in Soudade Kaadan’s humanistic Venice Audience Award winner that signposts its intentions when a character expresses surprise about the notion of “a film in Syria where no one dies”. Kaadan has one eye on a young adult audience, avoiding the out and out horrors of war that Insyriated made of a very similar siege set-up in favour of a magic realist-inflected tale where it is not just teenagers who are gaining their independence.

Young Zeina (Hala Zein) has just hit puberty and her apartment is like any number of suburban homes across the world, with its patterned wallpaper, comfy sofa and mirror on the wall. The only difference is, she and her mum Hala (Kinda Alloush) and dad Motaz (Samer al Masri) are just about the only ones left in their besieged neighbourhood of Syrian capital Damascus.

“This home won’t lack anything while I’m here,” Motaz declares, even though they currently have no electricity or running water and need him to go on regular food forays. Hala follows his lead. “Your dad knows everything,” she tells Zeina.

Things begin to shift, however, after a bomb drops on their apartment. Nobody is hurt but they’re left with huge holes in the walls and the roof of Zeina’s room. The production design rendering of this by Osman Özcan brings home the frailty of anyone’s existence in the face of conflict. Motaz’s denial, however, is complete, with him quickly declaring their bomb site of a house is “fine” even as he hurriedly begins to put up sheets to hide his family from what he imagines to be the prying eyes of the neighbours.

The hole in the roof of Zeina’s bedroom brings not just a view of the stars but an unexpected visitor. Amer (Nizar Alani), a teen of a similar age from a neighbouring family who brings hopefulness, the spark of potential romance and a load of technical equipment - rather too much to be fully believable in the established environment - that proves useful as the plot marches along. Amer’s upbeat attitude mirrors that of Zeina, who dreams of fishing and, in one of the film’s repeated magic realist moments is seen skimming stones across the sky as though it were a pond. These dreamy touches are, for the most part, nicely realised, especially when Hala later shares a similar moment, one of several nicely worked connections Kaadan draws between the two women.

Cinematographer Hélène Louvart has always had a way with light and here she and Burak Kanbir put it to good use here, as it spills into rooms or tunnels. There’s also a real intensity to a scene in which the two teenagers share a bowlful of berries, imbued with eroticism simply by the sudden close proximity of the camera. The character development feels somewhat abrupt compared to the visuals. Motaz is such a caricature that he feels ‘too big’ in comparison to the character of Hala, with Alloush playing her much more naturalistically. This becomes an issue when character development leads her to make a decision that feels more rooted in necessity for the narrative than development of the script.

If Kaadan doesn't quite get the dramatic weight to land solidly, she nevertheless has a fine eye for a poetic image, while her gently feminist optimism is likely to find particular favour with mum and daughter trips to the cinema.

Reviewed on: 01 May 2024