Eye For Film >> Movies >> William Shatner: You Can Call Me Bill (2023) Film Review

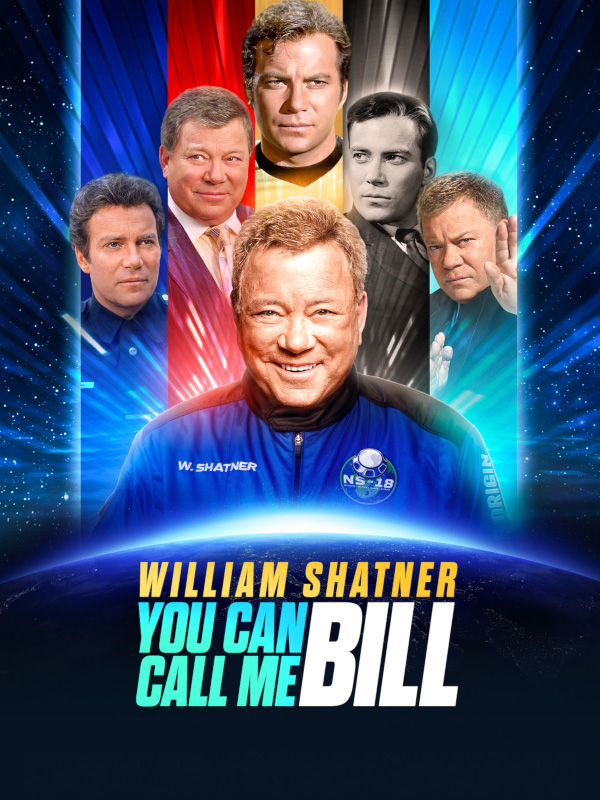

William Shatner: You Can Call Me Bill

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

With titles like Memory: The Origins Of Alien, Lynch/Oz and Leap Of Faith: William Friedkin On The Exorcist to his name, Alexandre O Philippe has firmly established himself as a director able to dig into well known subjects and find something new, but even he is up against it when it comes to William Shatner. In an interview-based documentary which skirts lightly over the star’s actual work to focus on his self-analysis and ‘philosophy’, Philippe comes up against a man as famous for his devotion to crafting his own legend as for any of his creative work. The phrase “there’s no room for ego,” is used again and again as the filmmaker struggles to find a route past what Shatner wants us to see, past the masks which he openly admits to wearing.

We begin and end with giant redwood trees. Shatner wants to talk about environmentalism, which is very decent of him and which makes sense given what he has seen during his 93 years on earth. One cannot quite escape the feeling that he is comparing himself to these enduring monoliths, but still, his concern for what will happen to the world after he leaves it is one which many older people will relate to – people used to reassure themselves that the world would carry on without them and it’s getting harder to do that – whilst providing a point of connection for young viewers. For him, this feeling is also closely bound up with his trip to space, which the film will address in due course.

In many ways the most interesting thing about Shatner is his age, and the long perspective it gives him, especially as someone whose focus has mostly been on the world as a whole rather than specific people within it. His reflections on humanity’s changing relationship with science fiction, science, space and the Earth itself over that period are interesting, if not particularly deep. There’s also a fair bit of material from his childhood which hasn’t been discussed much in the past, and which benefits from his seasoned perspective.

The obvious lingering damage from the beatings his otherwise loving father delivered, even though they were commonplace at the time, and his memories of his mother’s distance, his lack of friends at school, his struggle to feel that he really fit in anywhere, hint at a more complex human being beneath the carefully constructed veneer. His conviction that everybody else is masking too, along with his puzzlement at never having had close friendships, give the interview some poignancy. When he talks about his determination never to waste time with regret, viewers familiar with the larger context of his life might wonder if doing so could have given him the skills he needed to avoid alienating more of the people around him. He barely mentions the people with whom he has famously fallen out in the past, though his one reference to Leonard Nimoy is a reflection on how supportive he was at a difficult time in his life.

Most viewers who come to this film will probably do so because of their fondness for Captain Kirk, so it’s worth noting that out of the 96 minute running time, perhaps 20 minutes in total are spent on Star Trek. That seems fair – it was, after all, really quite a small part of his life in terms of the time it took up. he doesn’t have much to say about it that’s new, though it is interesting to note that just a year after its completion,. he was divorced and living in his truck. His memory of watching the first Moon landing – and the Moon itself – from that truck, on a lonely desert road, is affectingly reconstructed with the aid of animation, providing another glimpse of something that feels truly personal.

Wrapped around all this is a good deal of less substantial material. Shatner talks about tragedy and comedy, about his realisation that, if he could make people cry, he might be able to make them laugh as well. He has a fair bit to say about his experiences of performing comedy, both in TV and as stand-up. It’s just unfortunate that some of the moments when he’s trying his hardest to make a serious impression, reciting his poetry, come across as comedic as well. There are also a handful of clips featuring material which has aged badly in terms of how it refers to women, and the lack of contextual explanation means that it’s liable to feel very uncomfortable for a younger generation of viewers with higher standards.

The film and television clips used in the documentary seem to represent Shatner’s personal preferences – one gets the impression that he is always in control of the conversation, even when rambling – and as such they’re a bit hit and miss, dwelling in places on productions which are likely to generate little interest today. Scattered amongst them are small fragments of some of his genuinely great performances – in Roger Corman’s The Intruder, Stanley Kramer’s Judgment At Nuremberg, and episodes of The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits – but there’s nothing to let young fans know that these are the things they should be checking out if they want to see what he’s truly capable of.

For the most part, the film feels rather flat and not very revealing. It offers some interest for fans but it’s not the sort of documentary likely to intrigue people unfamiliar with its subject, to make them want to know more. Shatner has no doubt led an interesting life, but we never seem to get close to the substance of it, and there is nothing of the intimacy suggested by the title. Perhaps the mask has become so familiar that he himself no longer knows what lies beneath.

Reviewed on: 26 May 2024