Eye For Film >> Movies >> Small Things Like These (2024) Film Review

Small Things Like These

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

It is based on a book, the film, but sometimes adaptation is not translation but transubstantiation. That which is poured from bottle to cup is at first differently shaped. It's in the consumption, with belief, that it becomes something new. Something wholly powerful. Small Things Like These is an act as steeped in reverence.

I will usually track down a copy of a text made into a film. I've even a habit of collecting novelisations, a reversal of process that can produce arcane artefacts. The best-selling novel of the same name is not currently available from my local libraries. There might be something apt in the way they've disappeared into an institution. I might yet find but I do not feel the need. This is born of faith. The film is so capably constructed that I never doubt its intent. Its course never gives a moment where one might wonder if it has lost its way.

Birdsong and bells and the black screen. An opening rooted in Senjan Jansen's sound design, one of an ongoing set of layerings. If you stay past the end you'll hear similar over the credits. When the screen stops being black it starts being blessed. Frank van den Eden's camera grabs as much of the world as it can. Usually fixed, through doorways, through windows, to the back of a battered Bedford TK and so through its wide panes and across its curved roof. When it comes undone it catches haloes, when it comes unfixed it is as frantic as panic. Again and again it is as close as you are now.

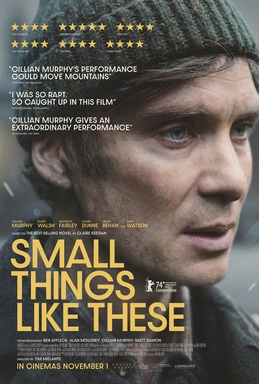

Cillian Murphy is incredible. As Oppenheimer one felt he could cradle the world in his hands and as William Furlong one feels he has it upon his shoulders. It is a performance of stillness and smallness and perfect detail. There are tools of chemistry like the touches of grey in hair and the dust of coal and bits of craft like costume and carpentry but it is all in the physical. A weariness, a wariness. It's a separation of dimension, not to stare vacantly into but to vacate a space. To be there and not there. To be here and not here. We are some minutes into it before his first words. "Very good", he says, but they don't mean that, they don't mean anything, and in that they mean everything.

Tim Mielants directs. He's done quite a bit of TV, including a few episodes of Legion, what I would argue is the only part of the Marvel associated television output that makes the argument for the medium. His most recent film followed an auxiliary policeman in occupied Belgium. Having seen this, I have no doubt as to the quality of the suspense and dread that he and his colleagues could conjure in 1942, because I felt it in his depiction of 1985.

I will pick one nit, which is that a window display features a Lego model released last year. Even if I didn't own at least a copy of set 31134 myself I would have wondered, as aviation and construction toys are two of my special interests. I'll forgive it though, for three reasons. The first is that the odds of anyone noticing it are slight, even if I've pointed it out to you here. The second is that it was the only detail in any scene where my awareness of it did something other than strengthen the film's emotional impact. The third is that, like the whisper of the auriga, it serves as a reminder of what is real. The driver of the chariot would quietly say "Remember you are mortal," "You are just a man." That's true.

The film is a story. Its subject is not. History can be an abstract thing though, however much flesh is behind the pages the pages are a barrier. Film, Ebert's machine for empathy, can unlock in ways text cannot. Small Things Like These uses all of them to do so. Murphy's performance is of such precision that the movement of carrier bags and tea cups and a bar of soap from a tin all matter but in ways that make them matter of fact. bill Furlong is alone even in company but Murphy is not alone in portraying him. Young Louis Kirwan in a debut role and with the help of those around him is a testament to that principle of the Jesuits. Give me the boy and I will give you the man. The last time I can recall two actors so perfectly occupying the same role was True History Of The Kelly Gang, a film I am delighted to weigh with this one.

The whispers aren't just that he is mortal. There's plenty evidence of that. There's a soul to worry about too, and those of those around them. As Oppenheimer we saw Murphy's eyes lit with the fires of creation, destruction, but by the hearth of Sister Mary they are lit with revelation at least as profound. Not with a bang but with a whimper. Emily Watson's role joins a canon of terrifying female authority, a canon that includes figures like Dolores Umbridge and Nurse Ratched. Messages said and unsaid, sealed and unsealed. Lives are as easily destroyed in boardrooms as in bombings, if you know the right buttons to push.

What motivates faith? Is it love? Fear of hell? Fear of hell for those we love? Love for those in hell? At times we catch Cillian against a dark background, a portrait of medieval anguish in a place of immaculate restoration. The concern on Eileen Walsh's face and Agnes O'Casey's face and on Michelle Fairley's face are reactions to what Murphy and Kirwan embody. I use the names of the cast rather than their characters because the who and how are part of the revelation. I do not know that I could ever with a good conscience describe a film as 'perfect' but this comes close.

Enda Walsh adapts Claire Keegan's novel. His best known work is probably still Hunger and the similarities run deep. Having mentioned Rome there's another bit of Latin apt, 'in loco parentis'. Often that is from a lack, a lacuna. Sometimes it's that the role of guardian has been occupied. That's not an accidental word. There's a discussion, between Bill and Eileen, of 'trouble'. They've five daughters. There's only a wall between them. 'Trouble', that's the worry. 'Troubles', that's what they called them. There's a few shots in the trailer of the back of Bill's truck, Bill's figure there in the cab. A coal and fuel man, a bringer of fire, of warmth. He is alone, and in that, singular. So too the film.

Reviewed on: 15 Nov 2024