Eye For Film >> Movies >> Once Upon A Time In A Forest (2024) Film Review

Once Upon A Time In A Forest

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

One of the hardest things to deal with in the face of climate change is our altered relationship with what’s left. This might not be the same for future generations, who will never have known the luxury of carelessness, but it’s challenging for those alert to what’s happening in this period of rapid transition. There are memories of celebrating the warmer months of the year by picking flowers, gifting them, wearing them, decorating rooms with them. Now the flowers are understood differently. They have to be left in field or forest, to feed the struggling pollinators. They, like all of us, have an urgent role to play.

Most precious of all are those flowers that spring up naturally – and the ferns and the fungus and the saplings and shrubs likewise – all the different players in ancient, resilient, wild ecosystems. Finland is 74% forest – that’s 225 thousand square kilometres – but around 90% of that forest is in commercial use. Whilst choosing sustainably sourced wood is a good thing, cutting down mature forest to create new plantations for it is not. Most forests have to be three to five centuries old before they achieve their full potential as carbon sinks. Young forests are nothing like as efficient. For this reason, all around the world, people are dedicating their lives to trying to defend the ancient forests that remain. This film follows some of them.

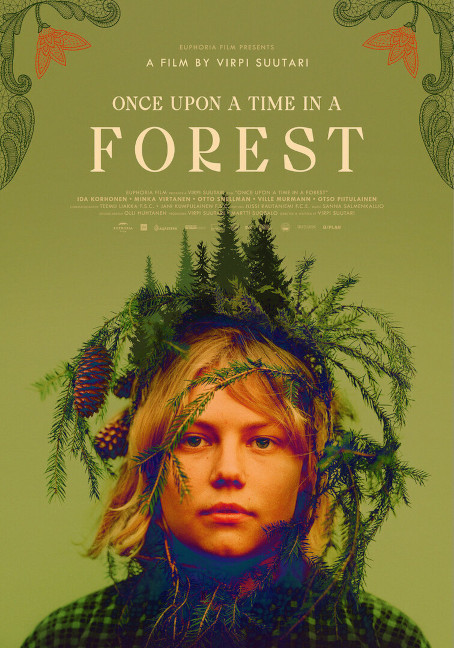

Screened as part of Docs Ireland 2024, it’s a film which uses experimental techniques to explore its themes, delivering something more like poetry than linear storytelling. Director Virpi Suutari’s camera plunges into the trees along with the volunteers, observing what they’re working with and capturing other details by itself. An experienced forest defender teaches newcomers how to distinguish the different species they find there, hoping to come across rare ones, which would make it easier to get protection orders in place. There is a considerable depth of knowledge here. perhaps concerned about putting off less academically-inclined viewers, the camera linger on the big round eyes of furry creatures snuggled into tree cavities.

There are different issues in different parts of the country. In the north, in Sámi lands, the reindeer herders want the forests protected, but don’t place much trust government – understandable given their historical experiences. Further south, the volunteers make the case for protecting forests which are younger but still have value. The obvious point is not made and it’s not clear that it is obvious to everyone – these forests won’t become mature unless they’re left alone.

Complicating these efforts is the difference in approach between generations of forest caretakers. Archive footage takes us back to the Seventies when young people realised there was a battle to be fought, but didn’t have the same scientific grounding that we do today. Young volunteer Minka argues with her grandfather, who used to clear old wood to plant saplings and cannot get his head around the idea of leaving fallen trees to rot, unwilling to acknowledge the now proven value of the natural processes of decay to a healthy ecosystem, horrified at the idea that thickets should be allowed to develop, essentially unable to accept that nature can take care of itself without human stewardship. He tells Minka to listen to her elders.

Elsewhere, young women in the movement complain about the way they are treated by some of the men their own age. They had hoped that a social space like this would be different. “The only difference is the length of their beard,” says one. They go swimming in a lake, moving through the cool water in long, elegant arcs, floating on the surface, and reflect on the likelihood of humans also joining the endangered species list not too far into the future. They feel guilt simply for being born into a destructive civilisation like this. Activism at least provides them with some psychological relief, whether they’re out in the forests or marching through the streets as part of increasingly large ecological protests.

Every now and again, Suutari shows us the paper factories where most of the felled trees go, sprawling on the horizon, belching out steam, characterised as doomsday machines. Psychologically, it’s an easy sell. For comparison, we have a magical vision of the forest on a winter’s night, thickly carpeted in white, with glittering flakes falling softly down. A man driving a logging machine chats amiably with an activist on skis. He’s happy enough to take the night off. The next day, she will be arrested, but it won’t deter her or her companions. This is a life or death struggle. Even if others don’t understand, or won’t play their part, they have to, just as the mushrooms have to shed their spores, just as the flowers have to summon the insects, just as the trees have to reach up towards the sky.

There is a lot of information in this film, but more importantly, there is an effort to explain, at an emotional level, why it is that they feel this way, why they make the sacrifices that they do. Suutari seeks to build empathy with the forest defenders and the forest itself. If nothing else, her documentary will stand testament to the fact that some people tried.

Reviewed on: 21 Jun 2024