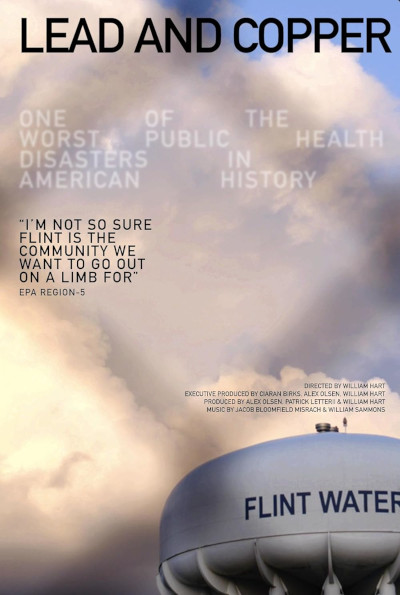

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Lead And Copper (2023) Film Review

Lead And Copper

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

For at least 10,000 years, humans have had some understanding of the importance of being careful about water hygiene. The earliest human settlements were usually built around springs, which generally guaranteed water free from organic matter and associated diseases. 3,500 years ago the Egyptians were using alum to remove obvious impurities from water, whilst Ancient Greeks and Indians boiled it and filtered it through charcoal. For all this time, clean, safe drinking water has been recognised as the most fundamental resource essential to life – and yet the people of Flint, Michigan, have had their tap water poisoned for ten years.

“There’s a definite sense of people being expendable in this country, and it’s usually along racial lines, and when it’s outside of that it’s along economic lines,” says one participant in William Hart’s documentary. We drift into the city across its adjacent great lake, taking in beautiful, open views that have changed little in a thousand years. It contrasts starkly with the run-down architecture and infrastructure of the town, which is home to around 80,000 people but has experienced little investment since the white flight of the mid to late 20th Century. That was when the banks left, making it hard to get loans, making it hard to go into business, stifling attempts at regeneration. Flint’s story is one of accumulated neglect, and that was the case even before this crisis hit it.

Is there a safe level of lead to have in drinking water? Not really, as several experts here point out. There is a level that is officially considered safe, however, and in the US, under the lead and copper rule signed into law in 1991, that’s 15 parts per billion (it’s 10 ppb in the UK). One woman here tells us that when, early on in the crisis, she felt ill and got her water checked out, the lead level there was 104ppb. By that time her four-year-old son had symptoms of poisoning including severe anaemia. A lot of the damage that lead poisoning causes remains with affected individuals for life.

How did this situation develop? Here Hart goes into detail, working his way back through known history and drawing on obscure documentation, expert insight and the testimony of local people to fill out the rest. Here’s the thing about the Flint crisis: even if you’re already familiar with it, even if you’re read or watched a lot of coverage, every time you encounter a new piece, the story is worse. Hart’s film is no exception. And if you’re shocked by the facts it presents at the outset, you’re going to be open-mouthed by the end.

People here may be poor, but they still take pride in their community. In the Civic Park district there are homes that have been passed down by families for generations. People can’t just abandon them. They’d struggle to sell them anyway, they don’t want to leave their extended families and communities, and others simply don’t have the money to move. They’re among the most vulnerable, because they don’t have the money for regular testing either. Over and over again they have been promised that the situation will improve. They have been given different advice and different filters. One woman describes how she boiled her water diligently for years, with no idea that that would be absolutely useless for getting rid of lead.

Beyond the price gouging by Detroit that first inspired Flint to go it alone, beyond the structural failures and delays and the theft of local democracy through the imposition of a city manager who immediately made a deal with the water company, we get the terrifying statistics: the estimated number of people affected, the number of children, the known effects on brain development. This, too, will entrench poverty, causing generational suffering. A boy screams because of the rash on his skin; an adult man tries not to do the same. There are revelations about the state of the pipes. Some of the things documented here constitute clear felonies. Will anyone be brought to justice? Some of the local people are fighting hard, but they’re up against giant corporations.

There is a wider story here, about the US and its water and how it views its people. Hart’s dense narrative is always involving but sometimes it’s hard to keep up, and then you may find yourself suddenly jolted by the realisation that people are no longer talking about Flint, but about Newark, in New Jersey – that more than one place has been affected like this. How many places have suffered, or are suffering, like Flint? The end of the film presents a list of county water systems with lead exceedances, and it goes on for several pages. This is the real horror – that its situation might not be exceptional at all. The potential consequences are hard to grapple with. Hart’s initially modest project has taken him into some of the darkest territory that documentary can encompass.

Reviewed on: 18 Nov 2024