Eye For Film >> Movies >> From Ground Zero (2024) Film Review

From Ground Zero

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

When we watch a tragedy unfold and a great many people are affected, there’s a danger that their sheer number will blind us to their humanity. All those voices crying out in anguish can come to sound homogenous. It’s part of a psychological defence mechanism which protects us from taking in the full horror of what is happening, but for those people, who need our help, it can be deadly. This is one reason why international journalists at publications not party to the omertà on the subject of the violence in Gaza have been struggling to bring individual stories to light. It’s a struggle which has been made more difficult by the killing of many local journalists and the difficulty in getting information out the affected area.

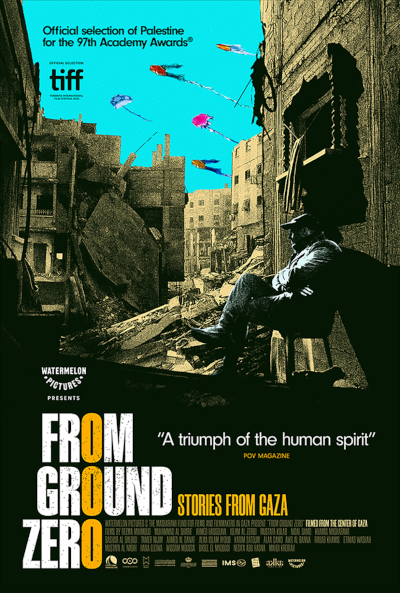

From Ground Zero is the result of a project by Rashid Mashawari aimed at enabling Gazans to tell their own stories through film. Given the conditions under which its creators have been working, it’s remarkable that it has survived and successfully made it to international screens. Not only that, but the work is strong enough that it would be worthy of attention under any conditions. Now it has been shortlisted for an Oscar. It is quite possible that some of those involved will not live to see the Oscar ceremony, but the film has become a beacon for all the world to see. It is testament to what is happening there, and it also contributes to the preservation of Palestinian culture, now more vital than ever.

The 22 films of which is is comprised are a mixture of documentary and fiction. It is not always clear which is which, but given the landscape against which all the films are shot, it would not be possible for fictional tales to stray very far from reality. There are a couple of experimental pieces here, but nothing that plays around much with genre. Nevertheless, the stories are highly personal and individual. It is the background observations, as much as anything, that makes the experience of viewing them sequentially crushing, and leaves one in awe of the fortitude of people still surviving there.

We begin with Selfie, one of several films set on the beach which runs along the edge of the Strip. The beauty of this setting, under clear blue skies, reminds us of Gaza’s potential, and presents a stark contrast to what we see elsewhere – yet we can still here the omnipresent sound of drones. Here a woman writes a message to an unknown recipient. She mourns her lost femininity, covers signs of fatigue with make-up so that her children never see how fear and lack of sleep are affecting her. She visits her old home, which is a mess but not completely destroyed, and is relieved to find her little orange and white cat, Reema, still present.

In the next entry, No Signal, a man searches frantically through rubble for his brother, Omar. His niece Nour, against his instructions, comes to help, and is told to stay on her phone trying to call her father, but forming a connection is only half the battle. With bombing still going on nearby, it is dangerous to stay. All around are the skeletons of concrete buildings. It is a landscape with which we will become painfully familiar.

Sorry, Cinema, sees a man who always wanted to be a director reflect on what it means to make films when there is not a single cinema still standing in Gaza. Now he uses the energy he put into production for survival, running towards descending parachutes to find food parcels. Like many of the filmmakers and characters here, he is recently bereaved, unable to fully process it because of the urgency of every moment.

Flashback features a woman who explains that she always has a bag of clothes packed in case she has to flee bombs or chase food parcels. She finds peace in studying, drawing and painting. The drones make a constant buzzing sound and she uses music, through headphones, to block it out, to try and avoid having flashbacks to her worst experience. She is one of several artists featured here, still finding a means of expression beyond engagement in the film itself.

In Echo, a man watches the sea as we listen to a past phone call with Yasmine, who doesn’t know what to do as the bombs are falling. In Everything Is Fine, a man feeding street cats reveals himself to be a stand-up comedian, determined that the show must go on no matter what, encountering appalling tragedy even in this context yet recognising the importance of resisting despair, of putting smiles on faces.

Soft Skin features animation made by children and also lets us look behind the scenes at their creative process. They share their thoughts. A girl talks about how her one-year-old brother can only say “Daddy,” and make the sound of an ambulance. Some have had their names written on their bodies in permanent marker by their mothers. One boy doesn’t want it because, he says, they’ll be in pieces if the bombs hit. The next film, Charm, observes children inventing games in a ruined street. A girl wanders away to dream black and white footage of traditional dancing, of studying in school, conjuring up memories of joyful times.

In The Teacher, an older man tries to entertain children with stones before beginning a difficult quest for water, bread and a chance to charge his phone. In A School Day, a boy living in a tent packs his schoolbooks into his bag and sets out on a walk, remembering all the sounds of school when he reaches his tragic destination. In Overburden, a woman walks along the coast, remembering how she and her family tried to leave Gaza, part of a long line of refugees who could not afford to get tired or drop anything. “It’s as if I were living in my books, guilty of leaving them behind,” she muses. Who chose to trap her inside her books?

We are only halfway through.

Hell’s Heaven sees a man wakes up in a body bag inside a tent, and try to figure out how he ended up there, to remember everything that he did yesterday. In 24 Hours, a man recalls being caught up in three attacks, and being buried in rubble, desperate to save the man buried alongside him. Jad And Natalie features a man sitting in rubble in the rain explaining that he has just lost Nour, the woman he was planning to propose to. The title consists of the names they had planned to give to their children.

Recycling is appropriately concise and systematic, but no less effective. People collect water from a truck and we see how the same water is used for multiple tasks, calling awareness to just how many day to day activities are disrupted in a situation like this. It’s followed by Taxi Wanissa, in which a man transports people around a city on his donkey cart. It stops abruptly, and its director appears to tell us about the impact of learning that her brother and his children were dead. She tells us what would have happened in the film if she had had the strength to finish it.

“Every thing of beauty is an offering to God, and we are the offerings of the present time,” says the woman we meet in Offerings. She became a writer because she wanted to break the familiar Palestinian narrative. Now she is displaced. She tells a family story about the Nakba to children. The memory of that conflict is often present in the background of the films, sometimes deepening despair, sometimes inspiring resistance.

Despair itself is the enemy for the woman in No, the most fiercely positive film of the bunch. She is determined to find a story of love, of joy, of hope, and eventually locates it in a group of young people who are making music. They sing about their belief that all this will pass and one day they will see beautiful smiles again. There is a direct focus on something we have glimpsed elsewhere: adults arranging fun activities for children to help them get through it all. After all the horror, some viewers will find this the film that finally allows tears to flow.

Teenage girls feature in Farah And Myriam. One has lost her cousin, whom we see being lowered into his grave. The other recalls being trapped under rubble for six hours, saved by the wardrobe that she happened to be tidying when her house was struck by a bomb and the rest of her family killed. The first confesses that she has become afraid of the night. “Whenever the sun goes down and the moon comes out, I lose somebody,” she says.

The pen and ink work of an artist is intercut with black and white footage of what life has become in Fragments. In Out Of Frame, another artist visits her mostly ruined home, where some of her work remains. Five pieces made up her university application project before the university was blown up. Two dove sculptures covered in pearls represented peace; now they look dead. Photos show her smiling beside the work back when it was exhibited. Then, finally, there is Awakening. A puppet show explores the tension between a worried mother and a restless child. The impact of an explosion restores the memory of a man who has not known them since the war of 2014. The story focuses on persistence: on continuing to sing, to raise up and educate children, to imagine a future.

Together, the films map out what it means to be in Gaza at this time. Not just the violence and the terror but the endless queues for essentials, the thick dust coating everything, the weight of trauma. In Taxi Wanissa, we briefly glimpse a Palestinian flag high up on a pole. It has been ripped apart, yet the wind still bears it up, bold against the sky.

From Ground Zero is essential testimony, and essential viewing.

Reviewed on: 28 Dec 2024