|

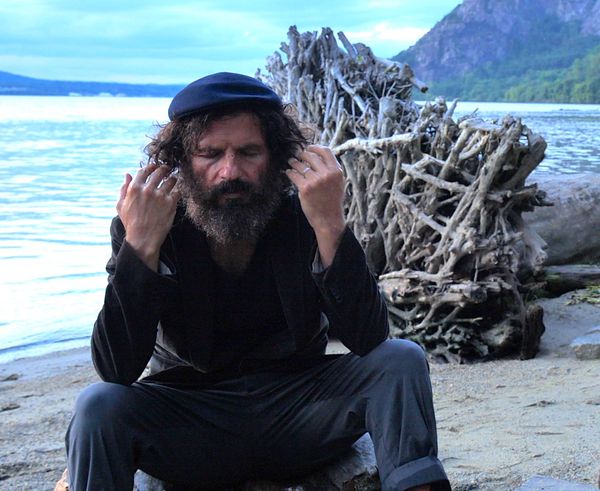

| Géza Röhrig in Richard Kroehling’s After: Poetry Destroys Silence: “It was really quite a magic tree there on the shore.” |

I first met Géza Röhrig when László Nemes introduced us at the Universal Pictures brunch in The Vault of the St. Regis for Danny Boyle's Steve Jobs (screenplay by Aaron Sorkin, based on the book by Walter Isaacson), starring Michael Fassbender as Jobs with Jeff Daniels as Steve Wozniak and Michael Stuhlbarg as Andy Hertzfeld.

Géza Röhrig played Saul Ausländer in László Nemes’s Oscar-winning Son Of Saul (Saul Fia, co-written with Clara Royer). He played Georges, the cousin of Marcel Marceau (Jesse Eisenberg) in Jonathan Jakubowicz’s Resistance, and Shmuel opposite Matthew Broderick in Shawn Snyder’s To Dust (co-written with Jason Begue and co-produced by Alessandro Nivola and Emily Mortimer).

|

| Géza Röhrig with Anne-Katrin Titze on The Way Of The Wind: “Obviously it has been edited forever, and we all know that Terrence Malick is a maestro.” |

He will be seen as Jesus in Terrence Malick’s highly anticipated The Way of the Wind (shot in 2019) and is currently filming Josh Sadie’s Marty Supreme, starring Timothée Chalamet. Rupert Wyatt’s Desert Warrior with Anthony Mackie and Aiysha Hart will feature him as well.

From New York City, Géza Röhrig joined me on Zoom for a conversation on After: Poetry Destroys Silence with an update on his career and life.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Géza, hi! Good to see you again!

Géza Röhrig: How are you? Good to see you too!

AKT: You're in New York?

GR: Yeah, I'm in New York. I have been in New York for 24 years.

AKT: I know, I meant that you might be filming somewhere. One never knows with you.

GR: I am filming, but it's mostly in Jersey.

AKT: What is the project? Can you say anything?

GR: Yeah, I think you might even have heard about it. There's a lot on the Internet. It's Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme with Timothée Chalamet. He's the star of the movie. I think it's going to come out in ’26.

AKT: Last time we met, you had just finished Resistance. Let's talk about your film, After: Poetry Destroys Silence, on this very particular day, which feels very much like a “Before”, doesn't it? [It was the day before the Presidential election on November 5, 2024].

GR: I know what you mean!

|

| Géza Röhrig on Richard Kroehling: “He's very creative, very experimental.” |

AKT: How did you get involved with After? Was it through your poetry? Through Son of Saul? The title After is clearly in reference to the Adorno quote [that poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric]. So tell me how you got involved?

GR: I don't know how Richard [Kroehling] found me. I have no idea how even he heard of me. He reached out and he came and visited me. We sat down for a coffee, and he explained, what this film should be about. I found the topic important. I mean, everyone unfortunately, has to relate to this. We all lose loved ones, and sometimes the measure is unimaginably hard. Historical events, and sometimes it's just a very small story, you know. Even losing a parent, or a sibling in an old age, it's just very testing.

As Richard explained, I think he was very interested in how poetry and writing can be helpful to go through this and so I was on board. I don't have that many poems of mine translated to English, but he chose a few and then we started to shoot. The rest is for his credit. He's very creative, very experimental. So there was not a very strict script that we followed. Sometimes he just showed up in a location and started to improvise things. That's how it went. We spent a couple days together, as he did with others. I mean, I am sure you saw the film.

AKT: Yes of course.

GR: I'm just one of the poets.

|

| Melissa Leo in After: Poetry Destroys Silence |

AKT: Where did you shoot? That uprooted tree is a powerful image. Where was that?

GR: That was, I assume, the Hudson. But, to be honest, my navigation skills are very bad. I remember my father when I was like three years old used to put me into a suitcase and walk around in the apartment, and then, after five minutes, I had to guess. You know, he put down the suitcase, and I had to guess if we are in the kitchen, the bathroom, or the living room. I never got it right. So it doesn't matter if I'm not in a suitcase anymore. I can be in a car and know everything, see everything. I still have very little sense of where we are, but I assume it was the Hudson, and it was really quite a magic tree there on the shore.

AKT: It's really poetic. It's very beautiful. You should make a short film just about a boy in a suitcase checking his sense of location!

GR: I know. And to make it a little harder, you know, my father died when I was four. This is really one of my last memories of him.

AKT: Wow!

GR: Yeah.

AKT: In After when we see you setting up the camera, it's very Buster Keaton. It feels very much like the beginning of cinema. It's a lovely moment.

|

| Géza Röhrig on Saul Ausländer in Son Of Saul: "I had a deep and personal connection with this subject matter." |

GR: That's all Richard. I had no idea that he planned it like that. Buster Keaton, yeah. He didn't share that with me. I just saw this in the ready movie.

AKT: It works very well. The fantastic poem “Open, Closed, Open” by Yehuda Amichai, was that something that you chose, or that you discussed together?

GR: I don't want to say something that is not true. Did Richard know that poem? Possibly. He's the most translated Israeli poet ever, so it’s very possible that he also knew it.

AKT: It's fantastic. It happens rarely that a poem can change your perspective on life so drastically in a few words. When you are talking about 1986 and your visit to Auschwitz, there's one line where you say that it was as if “I mean something to those objects” that they are “waiting for me.” Objects that remain speak to us. I think it's something that we have as children, and traces of it can live on. Can you talk a little more about that?

GR: When I went there in ’86, one of the first things I saw was a toothbrush. I mean, like a whole pile of toothbrushes that were taken from the prisoners, from the inmates, right away. I had a toothbrush in my own backpack, and that was the same brand. So these were Hungarians who were taken. And for whatever reason the toothbrush kept its name. So it was very strange. It didn't seem like something that happened very long ago. When I arrived it was a winter day, and for saving energy, the Museum of Auschwitz had the light on an automatic system. That means, if no one entered into the barracks after each five minutes it all went dark. So the second day I went there I brought myself a flashlight just in case it goes on dark on me again I can switch the light back. I can find easier my place.

|

| Géza Röhrig with Anne-Katrin Titze at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas for the opening of Son Of Saul Photo: Ed Bahlman |

So it was these objects, I didn't just see them in a way that they were meant to be seen. I saw them also with my flashlight, which also somehow made it very intimate. You know it all of a sudden. It was a winter day, the sky was very cloudy, so it felt a little bit with my flashlight like I'm in the middle of the night, like, spent the night there, which is obviously impossible because Auschwitz was not open after like 6 pm. I remember very much that there was a smaller mountain of fake legs for the people who were one-legged or something, and that was taken as well. So yes, these objects stayed with me, and they still do.

AKT: You then speak about how it changed your life. I had to think about the Rilke poem, Archaic Torso of Apollo. The line at the end: “Du mußt dein Leben ändern” - “You must change your life.” I think that all connects.

GR: Yeah.That's a hard thing to do. I wonder if Rilke changed his life or not. This is something that we aim for, a difficult thing. It's the hardest thing ever. I think even if we change our life, which is basically change ourselves even a bit. Just a small bit. That's already a huge thing. Someone told me that, you know, we are full of mechanisms. We are full of routines, and in order to change anything you have to do it differently 40 times, because then the old habits still will resurface, and the old, so to speak, will win the game. So we have to keep changing. It's not like you can just change once and for all. You have to keep changing, and for me losing anybody - you don't have to lose millions of people. I knew my grandfather survived.

Losing somebody is somehow similar a little bit to having a child. If you become a father or a mother you're never going to be the same person ever again. A new reality comes with every child. And the truth is, when someone dies who meant a lot to you, it also brings a new reality to your life and that is a very dangerous reality. What I'm trying to say is that at least in Jewish tradition there is an obligation to remember our friends or relatives. But there's also an obligation to finish grieving. There's always an obligation to stand up and to go on with life, because there's a certain whirlpool. There's a certain magnetism.

|

| A grave Albert (Matthew Broderick) with Shmuel (Géza Röhrig) in Shawn Snyder’s To Dust |

There's a certain danger to stop with the dead and to never be able to stand up and take a shower and eat again, and go to work and to move on with life. So this is a balance that has to be practiced. It changes your life. But there is also, like with everything, there can be too much of a change and that would paralyse someone to the degree that obviously our loved ones would not like to see. They would not like us to spend the rest of our lives thinking of them. That's not what they would like to see. They want us to go ahead, be happy, succeed. And at the same time remember.

AKT: To the point of the remembering, we are at a different point than when you and I first met and later presented the opening night of Son of Saul. We're living in a very different time already. I'm curious what you thought of Zone of Interest.

GR: I think Zone of Interest is basically going one more mile in the direction of Son of Saul. I think in some ways it could have not been done without Son of Saul. And I also believe that, as you said, that Zone of Interest was done a little later, like, I don't know, five, six years later than Son of Saul, and that matters a lot, because the whole of the survivors of the Holocaust are dying out. The people who are still with us, in their nineties, they were like 4 or 5 years old when it all happened. So that's not exactly the same way of remembering how a 4-year-old remembers things as a let's say, a 35-year-old remembers things.

So we are very close to a world where there will be no people left anymore who actually survived the Holocaust. I think that changes the situation in quite important ways. So I think that the genre of of the Holocaust movie, it's dying out with the survivors. I don't expect to see Holocaust movies very much. Let's say, ten years from now, there will be no Holocaust movies anymore. I'm quite convinced of that. There might be documentaries. But the way we used to have fictional movies about it, I think it's slowly drying up.

|

| Shawn Snyder and Géza Röhrig at Village East Cinema following the post-screening discussion and Q&A of To Dust moderated by Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: At the same time, there's still so much more information, so many more details that are coming out. Just that toothbrush that you mentioned. The small objects, the smaller things, or the new information that is suddenly available. I think that will continue. But it's a different approach. For example, just last year I found out that a relative of mine was murdered in Dachau in ’43 whom I had never heard of before. His name was Josef Czogalla. Research is continuing, but we will have a different approach.

GR: Yeah.

AKT: At the same time, there are other tendencies that want it all to be forgotten.

GR: I think that if history has a window, I think the Holocaust was in the window when it had to be.The whole time to understand what happened. And how could it happen? It all started basically in the Seventies, Eighties. It had a culmination. And about when the Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC and Schindler's List and all this happened, it had a plateau. It was very important for about 15, 20 years. And it doesn't mean that it will not be important for academics and for everybody who wants to understand good and evil.

We will all forever think about this, but somehow I feel that with the passing of the survivors that means that there will be no families left, grandmothers and grandfathers and the immediate direct link of having people around us who can testify, and who can say how it was. These people are passing, and it will become a history some ways. Unfortunately, like the Civil War, it's going to lose some of its …how can I say? So that's what I'm speaking about. I'm not upset about it. I'm just describing the fact that without the survivors it will not be the same.

AKT: It won't be, I agree with you. What are your projects after the Safdi film that you have lined up?

GR: Just a word on what I'm pretty excited about. It's not the project that is still in the future, but it's a project that we wrapped up right before Covid, and it's going to come out hopefully this spring, which is, I'm not sure if you heard about the Terrence Malick.

|

| After: Poetry Destroys Silence poster |

AKT: Oh, yes. And you play Jesus, of course!

GR: I'm very curious about it. Obviously it has been edited forever, and we all know that Terrence Malick is a maestro. He's taking his time, and he's working very intensely. So I'm very curious about that movie.There is another movie that's coming out in January, which I just saw this morning at a 9 AM screening. It's called Desert Warrior. It's a movie by Rupert Wyatt. And I have to say it's quite a movie. So I'm curious of what you think of that. It's coming out in January, in the theatres.

AKT: The Terrence Malick movie, I think, changed its name a few times. What is it now? The Way of the Wind?

GR: The Way of the Wind. Yeah.

AKT: Also I remember when we talked about Son of Saul, we had this conversation about drone warfare, and about somebody pressing a button in the desert and throwing bombs in another part of the world. I just saw Grounded, the new opera at The Met. Did you hear about it?

GR: No, not yet.

AKT: It’s about a woman pilot who becomes a drone pilot, a powerful story and exactly what we talked about. A friend of mine, Michael Mayer, is the director, and it premiered this season. So I thought about you.

GR: Amazing. I'll check it out.

AKT: Good to talk to you.

GR: The same. The same here.

AKT: I very much am looking forward to seeing you as Jesus and as anything else. I liked your performance in The Chaperone, by the way. Very different!

GR: Yeah, very different it was. It was entertainment, but in a very loving way, you know.

|

| Géza Röhrig on his next film: "It's Josh Safdie’s Marty Supreme with Timothée Chalamet." Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: Louise Brooks, before GW Pabst.

GR: I think the demographics were more like, you know, female viewers like 60 plus, that's what I heard. I quite liked it, and usually I don't do films like that but it was a lovely, lovely team.

AKT: Elizabeth McGovern is lovely. I stumbled upon it because of the subject of Pabst, and because of Louise Brooks, and though I’m not that demographic yet, I enjoyed it.

GR: No, you’re not. But thank you!

AKT: Thank you!

GR: Bye-bye, all the best!

After: Poetry Destroys Silence is in cinemas in the US.