|

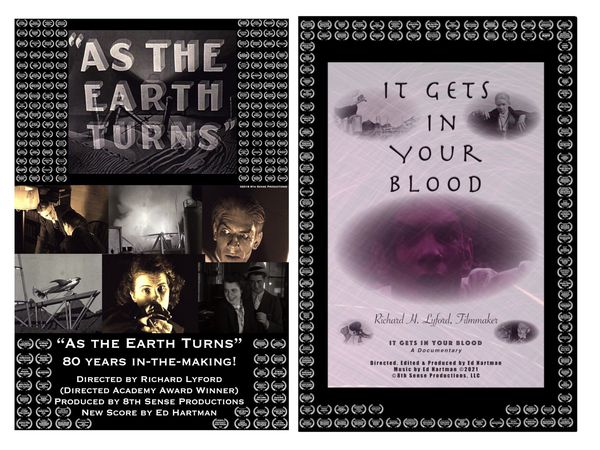

| Posters for Richard Lyford's As The Earth Turns and It Gets In Your Blood Photo: courtesy of Edmund Hartman |

An extraordinary talent who created innovative, forward-looking works like As The Earth Turns in the early 20th Century, Richard Lyford may never have become a big name in Hollywood, but he retains a dedicated following to this day. One of his admirers is Edmund Hartman, a producer and composer with a passion for this exciting period in cinematic history. He’s recently restored a previously lost Lyford film, The Scalpel, and we took the opportunity for a chat about Lyford’s work.

For him, he says, the interest in Lyford began on the Classic Horror Film board, which is used by quite a few producers and directors. Two of them had discovered a video that caught his interest: Monsters Crash The Pajama Party.

“It was put together by Something Weird Video for Halloween, and in it were two fragments. Nobody knew where they were from. These guys just got into it, and they wound up discovering that this guy Richard Lyford had made them. How they figured it out was Lyford was that he had written articles in American Cinematographer about his work, because he made nine films before he was 20. And the fact that he was able to write articles in American Cinema Photographer is pretty amazing because I've talked to directors who said, ‘You know, I've been trying to get an article in there for 20 years.’

“Anyway, they figured it out, and they wrote up quite a bit, and it's still there. It's quite a thread. So anyway a couple years later, they got connected to the great niece of Richard Lyford, Kim Lyford, and she wound up getting involved in it and eventually contacted Chris Lyford, who's Richard's son, who lives on the East Coast and wound up taking on the film estate for safekeeping. That's the physical film estate, and then the intellectual property as well. And so he brought it to her in Seattle in 2017.

“She saw that I was scoring films, and she asked if I was interested in maybe scoring one of the particular films that she found, called As The Earth Turns. She had been digitising everything and she showed it to me. At that time it was about 30 minutes and I looked at it like, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’ So I wound up scoring it. I got more involved. I discovered in the digitised files another 15 minutes of that, and wound up becoming editor, putting it together. I really wasn't sure, but it seemed to make sense. And this was after I started scoring, which is kind of scary because you're synchronising things and all the rest of it. So anyway, so we got it done. And then, as you know, that film got into all sorts of film festivals. It's on Amazon, Tubi and all that sort of thing. It was on Turner Classic Movies a couple of times, which is pretty incredible.

“Eventually she gave me the film estate and the collection. Most of the stuff he did was commercial, military, educational sort of thing. Eventually I followed up with Something Weird because I knew they were in Seattle and they're an exploitation film distributor. They confirmed that they had the two fragments from the video because they weren't part of the original physical films that I got. And so I got them and they were Ritual Of The Dead and The Scalpel, but there wasn't the complete Scalpel. It was the second half.

“I wound up scoring those and those got into the DVD that I wound up creating, of As The Earth Turns. That was released 2021. And then this year, in 2024, I was preparing the films for transfer. I figured out that Periscope Films in LA might be the best place for these films because we had them all digitised. They're a really cool archive and stock film company in LA that I got to know. And I was going through the films for the final time.

|

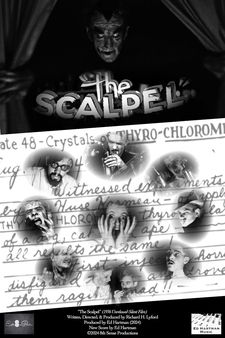

| The Scalpel poster |

“I have a 16mm editor and there was one can I hadn't seen – and it was the first half of The Scalpel. So we wound up digitizing and it was kind of washed out, it was kind of light. It had slightly different intertitles on it as well, which is a little strange, but over time we got some other companies involved and rescanned it frame by frame, really high quality scanning, and then colour corrected it. So it actually brought together some of the same team from a couple years before with As The Earth Turns, which is kind of cool. And it came out great. Amazingly, it perfectly matched the second half of the film.

“Now, if you think about this for a second, the second half of the film came from the East Coast and the first half came from a couple of miles away from me, from this company Something Weird in Seattle. I mean, that's astounding if you really think about it, that they matched back together. Because I've been getting involved in reading about his articles and things like that, I was able to verify that I had the complete film based on length as well, and the story kind of made sense,. This was his sixth of nine films, so it wasn't quite as tight as As The Earth Turns, but it's pretty well done.

“When I score, I use Logic, which is a digital audio workstation. Because of the way I score, I tend to write piano parts first and then break them out into orchestral. And luckily I kept the original score for the second half, so I was able to match themes and things like that. I was able to get the same mastering guy who had done the first half and As The Earth Turns, and that was pretty cool too. So everything was matched up very well. And again, the quality of the film was really pretty good.”

It's great the way these things are being discovered now, but was there much visibility for them when they were first made, beyond Lyford’s family and local people?

“No,” says Ed. “And this has been of a concern to me, because anytime you're taking over an archive and you're releasing things from somebody's life, you really don't know what he thinks about all this stuff. But I did about an hour and a half interview with Chris a few years ago for the mini doc, and he reassured me. He said his dad loved those films. And I thought about this. I mean, I started making Super 8 films as a kid and I made a very deliberate decision, going to college, to choose music school. And there was part of me that was probably going to head to LA and make films. I mean, I was pretty serious about that idea too, but I was more into music at that time.

“So this is kind of a third act for me, coming back into film. Anyway, some of those films I made, as stupid and silly as they were, they're pretty fun to watch. And when I think about music I wrote, especially when I first came out here in the Eighties, it was pretty good. So as far as releasing these things, when he was 20, he had done As The Earth Turns and pretty immediately went to LA and got connected with Disney. My feeling is that there was no place to do anything with these films. They were 16mm, they were silent because he didn't have modern sound capability. Although he was working with dual turntables synchronizing to a projector, which is pretty amazing.

“If you're working with a deceased director, you don't know if, what you're doing to his film, if he's going to hate it anyway. What we did discover was the types of music he liked. Stravinsky, Dvorak, things like that. Chris reassured me, said ‘No, your music would have been right on to what he was looking for.’ So I feel pretty good about that. But again, you're messing with people's stuff before they were so called professional now.

“I think the best they were played was in his family's basement theatre, and maybe at the high school or maybe a theatre here and there, you know? My theory is that he did bring them along to LA, and that was probably how he got involved with Disney.

“One of the reasons he made these movies was for contests, essentially the film festivals of their day, and the American Cinema League. Scalpel won an award and it was written up in the amateur section of American Cinematographer, so we have a lot of information on that as well.

“There's a twist that I'm starting to look as another serendipitous moment here. Karl Struss made Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde in 1931. He was well known as a cinematographer – he did Sunrise by Murnau. This is one of the great cinematographers of all time. And he was also a judge of these little competitions, and The Scalpel was on there. Well, this is interesting because you notice the transition scene in The Scalpel.”

He’s referring to a moment when the villain of the piece, an obsessive scientist who has taken to experimenting on himself, mutates before our eyes – not an easy thing to pull off with the technology of the time.

“It wasn't a normal fade,” Ed observes. “Kim said ‘I think it was done with lighting.’ And last week, there was this article about the 1931 Jekyll And Hyde, about Struss doing that transition by using colour filters against black and white. What was really amazing about this is that Lyford was doing this at 19 years old. I’ve got to wonder, did Frederic March [star of the Struss film] ever see The Scalpel’s transition and think ‘Man, who is this kid?’ These little twists really add mystery to the whole story. I get more impressed when I see this stuff and I start digging a little bit and inevitably another little morsel comes out.

“What's frustrating for me is I have basically two and a half out of his nine films. Ritual is just a fragment. There's another six and a half films out there, which I've tried to reach out for a little bit, but the chances of getting them discovered are...” He shrugs. “Who knows? But, of course, none of this would have ever been except for that video coming out. Otherwise this stuff would have sat with Richard's son in New York, and who knows what would have happened to it. We think Richard probably sold his films for money later, and that's why they wound up in different places.”

I ask about the inventive special effects work in The Scalpel, and how much Lyford contributed to developing cinema technology.

“Well, again, who knows? But he did write about it in American Cinematographer in detail. And so anybody that was reading that – directors, cinematographers – would have picked up on this stuff in Hollywood. They had moved to 35. They had moved to sound, things like that. I think that Lyford's dual turntable system probably attracted Disney because he was trying to figure out cheap ways to make sound films on 16mm. I think they were impressed with Lyford's ability to come up with things like that.

“I know that sound film was something he really wanted to do. The first sound film he actually tried to complete was The Sea Devil. It had just 100 people involved, and it had 49 sets. There was a crazy amount of stuff going on, and in the end, he wasn't able to get the dialogue and the music in sync like he had hoped. So at the première in his basement theatre, they actually faked the sound from the sound booth, hitting stuff and doing dialogue through a small microphone and things like that, because he ran out of time trying to get it done.”

We go on to discuss some of Lyford’s other works.

“Ritual of the Dead, that's a mummy film and that's pretty wild,” Ed says. “Again, it's just a short fragment. At one point he's got an axe and you see him chopping away at somebody – so he was pushing the envelope a bit. Horror film is very popular in film festivals and I wonder, why is that? I'm not especially a fan of horror movies, although I love really good psychological horror like The Haunting from 1963. That's the greatest horror film ever made because you don't see anything, it's all in your head. But Lyford did it very well.

“My reasoning on this is, I think when you're an early filmmaker, comedies and dramas are very hard to do because you have to have really good actors. In comedy especially, what is funny? Who knows? Most comedy directors are afraid to death that their scenes aren't going to be funny, even when they're geniuses. Mel Brooks was like, ‘I don't know if this is going to be funny or not.’ But horror, even if it's lousy, it's funny, you know? So I think you can get away with a lot with horror films and I think that's why he chose them. As The Earth Turns is a pretty smart sci-fi film. I think that was a big move for him.

“The Sea Devil, that was a film about Count von Luckner, who was a German military guy in the first World War who would only take on military ships. He didn't want to hurt civilians. When Lyford decided to make that film, he moved it into a modern era where it was like submarines and stuff like that.”

Later on, he says, Lyford’s career was interrupted by World War Two.

“Disney lost maybe 23 staff people to the war. There was a Disney exhibit in Seattle that was floating around the country about Disney and the world of war, and I went there specifically to find evidence, and there was one pretty big listing that showed all the people that went to war from Disney. Richard Lyford was included on that. He worked for the Army Air Forces and I'm sure he had an adventure and a half. He was that kind of person. I don't think he ever really rested on his laurels.

“He was always like, ‘I'm on to another thing.’ Even from being a kid. As soon as he was done with one film, he was out raising money to make another one. This is typical filmmaker stuff. It's what everybody does to this day. But he had to raise money just to buy film, you know? He'd always been an independent guy. I'm not sure he would have survived at Disney that long anyway. But I think he probably would have found his way into Hollywood and maybe become a fairly big director. Chris said they watched Raiders Of The Lost Ark and Richard said ‘I would have loved to have made that movie.’

“Now he did make The Island Of Allah, a historical drama, which was narrative in a way, but that was about it as far as narrative filmmaking went. I would have loved to see more of this kind of stuff myself.”

Was Lyford part of any filmmaking collective? Was he in conversation with other filmmakers when he was working on these things?

“I can assume he was. He worked with Robert Snyder and Robert Flaherty on the Michelangelo thing. Flaherty goes back to Nanook Of The North and Snyder had made tons of stuff, and got the Academy Award because he was the producer. So I'm sure he got to know a lot of people. But he lived in New York a lot of the time, especially in those important years after the war, and he developed his own company there. He was maybe a little out of the loop at that point. He did get back to LA in the Sixties and Seventies when he was working for Disney again on some interesting documentaries he was doing, so at that point he was probably connected.

“There's an interesting film called Africa In Motion that he did for the New York World's Fair. It's expensive. Ossie Davis does the narration on that. We have the scan of that. It was a very washed out 35mm film, 10 minutes. It was a film that you would have seen as you're walking into the pavilion, and it was kind of a little intro. A really well made film, just incredibly crisp. And the scan was unbelievable. The correction that was done was incredible. So he knew these pretty well known actors and people like that. I can imagine he got to know people pretty well.

“If you want totally flip this into the future, the influence he's having right now is huge. I'm going to these festivals and there could be 60 or 70 filmmakers in there and they're watching these films from the Thirties done on 16mm silent. They come to me and they go ‘Who was this guy?’ And I keep saying ‘Yeah, no kidding, read about it.’

“The tools he had for this were minimal, even for the day, because he really wasn't a professional. So I think they can relate to him. And I believe that contribution may eclipse everything. I'm proud to be part of that as well.”

If he could have just one of Lyford’s last films, I ask him, which would it be?

“Wow. Ooh. Well, it'd be great to see the other half of Ritual Of The Dead, because we have half of it, but I think The Sea Devil is the one I'd want to see because that was his biggest production of that point. I will say one thing. There's this midnight adventure film that he did very quickly, and it's an interesting story because As The Earth Turns was going to take too long to finish, so he couldn't put it into a contest. So he decided, ‘I'm going to do a film,’ and he played five parts. Maybe one other person was in it, and he got it done in 48 hours and sent it in.

“This guy did this when he was 18 years old, you know, with film. That means he had to develop the film, he had to do the whole thing. So that's one I really would love to see. But, you know, The Sea Devil, that's a pretty huge undertaking just to see all the sets and models that he did.”