|

| Noah Wiseman in The Babadook |

“If it's in a word or it's in a look, you can't get rid of the Babadook.” So the story goes, and indeed, this sinister being has proven to have remarkable staying power. It’s now ten years since The Babadook was first released, and he’s returning to cinemas all over the world in celebration. Though he had his origins in highly successful 2005 short The Monster, his creator, Jennifer Kent, tells me that she never had an inkling of how her film would be received.

“I genuinely didn't. You always hope as a filmmaker that you're going to make something that people see and, you know, most films then come and go, but for it to have this afterlife has been so exciting. I'm quite a private person, so to be honest I had to be coaxed into celebrating its ten year anniversary, but I'm so glad now that I'm here. I'm in New York at the moment and then heading out to Austin to be part of Fantastic Fest’s jury, and they're doing a screening of it there, and then I'm going to LA for some screenings there as well. It’s lovely.

|

| Noah Wiseman in The Babadook |

She confesses that she can’t say what has given it so much staying power.

“What I can say is I wrote this from the centre of my being. I wanted to write a film that was very meaningful to me and then hopefully it would be meaningful to others. But I think you can never really know, as the originator of the material. You can't know how it's going to affect people. It has a bit of universality, I guess. People ask me what the film's about. Well, they say it's about grief, but for me it's really about suppression of feelings and how that can really take you to a very bad place. So that's something that all of us can probably relate to.”

I tell her that it felt to me, when I first saw it, that it was talking about something that people were only just beginning to have conversations about in society at large – suppression of feelings, and also the specifics of women not always feeling able to love their children as they’re expected to.

“Yeah. I thought I was going to be vilified for that, to be honest,” she says. “I was really worried about how that was going to be received, and unnecessarily so. But I think, you know, I actually got a response from quite a number of female audience members saying ‘Thank God she's not perfect! Thank God this is a complex character who you feel for, but she's not being a great mother.’ And, you know, where do we ever see that? We don't see that in cinema very often. It's usually the archetype of the all loving mother. It's very taboo to even talk about the difficulties of loving a child. It's not easy for every mother all the time.”

It also takes on the taboo of children not always being easy to love, I suggest. Sam is very aggressive at times. The Babadook feels like something has come from both of them and from the tension in their relationship rather than just one of them.

“That's really insightful, actually,” she says. “I don't think I've ever heard anyone say that, but I think it's true in that it's a condition that's arisen from these two people and their dynamic. It's not just created by any one thing, you know? And that's fascinating to me. It's almost like an energy of the relationship in a way. That's one way of looking at it.”

It feels like something that has more power because it's got a grip on both of them in different ways, and they feed that back to each other.

“Yeah, yeah. People ask ‘Is it metaphorical? Is it supernatural? Is it psychological?’ And I say ‘Yes,’ because it's whatever people see in it.”

It doubtless owes a lot of its power to the remarkable performance by Noah Wiseman in the role of Sam.

|

| Essie Davis in The Babadook |

“I think he was an exceptional child. The first thing we did was audition hundreds of boys. My casting agent auditioned a lot and then narrowed it down. You know, some children just don't have the skill to act, but we I watched all of the greater shortlist, and Noah really stood out. We got him in. He improvised things. I remember distinctly his skills at improvising. I remember he created a basement because I gave him a bit of this story, with a basement in it. So he went to the table and mimed opening a door with a key, and then walking down the stairs that weren't there and then doing stuff. And then when he came back, he locked the door as well.

“To me, that communicates an incredibly imaginative child who has this visual, imaginative world that's really alive. So I did a lot of auditioning with him, and then once he got the role, I really had to teach him what acting was, because he didn't really understand. How could he understand, you know? The process of filmmaking was something that had to be real to him. I did take a lot of time and effort to make sure that he understood the whole story of the Babadook, because can you imagine being five or six, not understanding what's going on around you? It would be bizarre and frustrating. So I told him the story from Samuel's perspective, and he was able to really be in the centre of that experience as a result.”

We talk about the creation of the book where the ‘Dook first appears.

“I wanted it to feel very much like a children's book. You know, one of those older style ones that just feel a little sinister, even ones that are made for children. I wanted it to really feel like, ‘Oh, here's a book. Did we get it as a birthday present? I can't remember.’ It just appears and it very quickly becomes sinister. But I knew that it had to be a pop up book. I knew very early on that it had to be handmade, which it was. It was the thing that we built first and then the world, the film, we built around the style of this book. So it was hugely important.”

Part of the monster’s appeal is his very distinctive look. I ask if he was inspired by the figure of a man wearing a hat that a lot of people see when experiencing sleep paralysis, but it turns out she’s unfamiliar with that.

“I wanted to feel this kind of hokey, kind of gentlemanly quality,” she reflects. “It's also a heavy disguise because if you look at the illustration, it's actually a mask, you know? It looks fake, and with his hat and everything, every part of his body is covered. You don't see skin, really. You see a coat and hat and black gloves, but that's just something playing at being human. So that's the effect that I wanted. I was very influenced by George Meniere's and Lon Chaney's London After Midnight, which is a lost film, and there's photos still that look macabre, and he's dressed in a top hat.”

|

| Essie Davis and Noah Wiseman in The Babadook |

I love those older influences in the film, I say, and particularly the way that the house is shot so that it looks more like the book as the film goes on.

“Yeah. And we deliberately bled the film of its colour. it started with a limited color anyway, but then it just bleeds down to almost like one. And we really did that in camera. We took out a lot of colorful items so that you started to feel more and more unsafe. And also in terms of camera framing, you know, the framing at the beginning is very central, and then it starts to veer off. Actors and characters start to appear on the edge of that Cinemascope format, and it's scarier because there's a lot more negative space.”

She’s made it clear previously that she never wants there to be any kind of sequel, but the Babadook has become something of a cultural icon. I ask her how she feels about that, and she laughs.

“I think that's the sequel. I think, in a way, that's the second life. People can enjoy the film, and there's no greater compliment than having a love of the films be kicked off in another fashion. I've been amazed by this LGBTQ inclusion. It's sort of confusing initially and then hilarious, and I just have gotten a real kick out of it. It's been very funny and wonderful.”

We talk a little about what’s been happening in her career since, The Nightingale and her contribution to Guillermo Del Toro’s Cabinet Of Curiosities, before I inadvertently kill the mood by asking about long-cherished project Alice + Freda Forever, which is based on the true story of a tragic romance between two women in late 19th Century Memphis.

“That film was killed about three weeks out from production,” she says. “It was a very painful experience that I don't really talk about that much. It really devastated me. I didn't even know that this could happen, but it did happen to that film. We have been attempting to remount that film, because I just won't quit. I really love that story. So it's still in my heart and we're still moving forward. But I've written about six scripts since then, and there's something very exciting that looks to be happening next year. Probably we can announce it in a couple of weeks. It involves horror, but horror fantasy, and I'm super excited about it.”

She’s done a really good job, throughout her career, of keeping control of her projects. Is that a major factor in how she chooses to move forward with any film?

“It is. I mean, it's a lot longer than I would have liked between films, to be honest. Alice + Freda fell apart in 2021. Since then it's been about me writing, but I am very particular. I've been offered a lot. I still get offered a lot of stuff which, you know, some of it's good, but if I'm not authoring it, and if I don't have a really deep connection to the material, I won't take it on. So it's probably meant that I've made less, but I've really proud of what I have made. And I think ultimately, you know, to be making this film I care about so much next year, it's all worth it.”

|

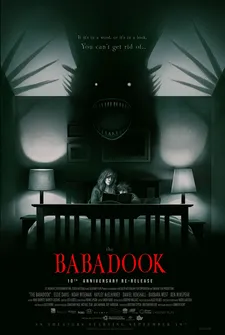

| The Babadook 10th anniversary poster |

Whilst looking forward to the future, she also has a strong attachment to film history, and at Beyond Fest later this month she’s going to be introducing a screening of Robert Bresson’s 1926 film A Man Escaped.

“I have really not seen any modern films this year, except maybe one or two here and there,” she says. “I've been going to the local cinematheque in Brisbane where I live, and seeing all sorts of wonderful films there for free. It's part of the Gallery of Modern Art, and most of the films are put on for free. They had a Robert Bresson retrospective, so me and my sister went to many of these films together. I actually saw A Man Escaped alone, and it just made such a huge impression on me. I'd never seen it. There were a number of other films of his I had seen, but it's just such a particular film.

“I think Robert Bresson had this devotion to purity in cinema, and he actually, in the process, created his own kind of cinema, and I really want people to see it. I was approached and I was told ‘You can screen any black and white film that we can get,’ and that was the first one that came to mind. Of course, there's hundreds of others come tumbling in after, but, yeah, I'm really excited about it.”

A Man Escaped is screening at Beyond Fest on 29 September. The Babadook screens in cinemas across the US from 19 September, accompanied by an exclusive director Q&A.