|

| Tomás Gómez Bustillo: 'One of the first inspirations for the film was this image that came to my mind of this glowing figure in the middle of the dark' Photo: Hope Runs High |

We spoke to Bustillo shortly after his film premiered in the US, and he shared his journey into directing, discussed the image which originally inspired the film and remembered his days as a Catholic missionary. He also talked about the significance of building filmmaking communities and previewed an upcoming project he's producing.

You studied political science before becoming a director. Can you share the path that led you to a filmmaking career?

Tomás Gómez Bustillo: It's kind of strange. At first, I didn't even think of film as a profession. So, after high school, I did one year of architecture and I realised that it was just too functional. It wasn’t as exciting as I thought. So then, at the time, I remember, I was feeling this kind of spirit that you have when you're in your early 20s and you feel like you want to change the world. I thought the best way to express it was through politics. And I was convinced that was my path to becoming of use to humanity.

|

| Tomás Gómez Bustillo: 'I remember saying to my therapist - if only there was a career that combined architecture, music and acting. It just kind of made sense that my career would be in film' |

What was the starting point for this feature? How much was it inspired by real events?

TGB: I think the idea has a lot to do with my upbringing. I was raised in a very Catholic family. And in my teens, I used to be a Catholic missionary in the small town where we shot this movie. So, I went there over several years and I met with those people, particularly the elderly ladies - they were the only people who were interested in having conversations with us. I did that for a couple of years. Eventually, I left Catholicism but the affection that I had for this town and those people always remained. They form the world that I wanted to bring to life in this film.

Having experienced this small town in your personal life, how did you explore its shapes and colours as a filmmaker?

TGB: The town feels cinematic to me. I always felt like it was a little magical place in the middle of nowhere, and I thought that hopefully, I would be the one to bring it out into the light for the world to see. It’s a very hidden place. There are only 200-300 people. It's very quiet but very beautiful and it feels kind of suspended in time, which I think is a quality that comes through the space and even the vegetation. Everything about it felt kind of lost in time, which is an aspect that I think informs me the most.

This quality also seems linked to how smaller towns act as spaces where myths and religion are more tangible compared to larger cities. Was this something you were looking to explore?

TGB: I don’t think there is a clear dichotomy between small communities and cities. They’re just different religions or myths. I live in Los Angeles and here wellness is a myth in some way. You know, it's like a mythical system. And that has the same validity as the ideas that started the film, which come from Argentinian rural myths about wandering souls and flashing lights. Who's to say which myth is better or more effective? It’s all about a personal opinion. Hopefully, this is something that's reflected back to the audience. This idea that the way we experience the world has so much to do with these narratives that we have about ourselves, and our place in society. And that those narratives can be just as strong in that small religious community as they can be in a city with people who are agnostic. At the end of the day, they’re narratives because we are story-minded animals.

The film captures how our reactions to these narratives create tension. We see this in the competitive religiosity between Rita and the locals. Did you draw this aspect from personal experience, or was it something you introduced through the writing?

TGB: There's definitely competition, particularly in the older demographic. Usually, it has to do with who's the most pious, who prays the most, and who gets the most attention from the priest. It’s its own little world with its little mechanics. I'm not saying it's always competitive, but it can be very competitive. But when I wrote the script, I was in my last year of film school, which is also a very competitive environment. I’m now thinking about the way we were all measuring each other up and comparing our writing. And we were trying to get the attention of film festivals instead of priests. So competitiveness was a feeling that I was going through at the time, and still go through. But reflecting these sorts of dynamics in the film felt honest and true.

The film’s tension, which comes from the competitiveness and solemnity of religion, is often diffused with humour. What was your approach to infusing comedy into the story?

TGB: The humour was always part of the film’s DNA for me. One of the starting points was my effort to stop taking myself so seriously. In film school, I had spent so much time trying to be the next Tarkovsky, when actually I just wanted to have fun like Jacques Tati and Aki Kaurismäki. So I tried finding comedy in the world that we live in, but a particular form of comedy which I like, less focused on language and more on physical humour, kind of like in Chaplin’s films.

The actors play an essential role in the development of this deadpan style. Could you describe your experience with the casting process, particularly with getting Mónica Villa on board for the role?

TGB: Casting was a twofold process. First, we had a traditional casting with amazing casting from Argentina and they were the ones who found pretty much everybody but Mónica. They really helped discover people that I've never seen before. For example, they found the actor who plays Angel (Nahiel Correa Dornell) and I think he's incredible. And it was very cool to see how they were thinking both traditionally and outside the box because they hadn't been able to read the script in this tone that we're talking about. And then we found Mónica through the DP Pablo Lozano, who knew her son from school. After getting in touch with her and pitching the story she said she was interested, and fortunately came on board a day later. I would say it was a very miraculous sequence of events.

How did you work on creating the deadpan tone with her and the rest of the cast?

TGB: Once we started working together, I gave Mónica and Horacio Marassi, who plays her husband, some film references. The list included Kaurismäki, Melville’s The Samurai, which is deadpan but in a different direction, and this fabulous 2004 film from Uruguay called Whisky. They looked at these references and kind of understood what I wanted. So at rehearsals, the fun for us was just perfecting the tone even more.

Light and the contrast between light and darkness is a key aspect of the film. What was the thought process behind creating this interplay around light?

TGB: One of the first inspirations for the film was this image that came to my mind of this glowing figure in the middle of the dark. So from the very beginning, it was that sense that the light should mean perfection or beauty, but it meant sadness in this image, for some reason. And that contrast was kind of a guide for how we should approach the light in this film. Usually, you associate light with clarity, perfection and safety, and darkness with mystery, or danger. But my approach to light was similar to how Rita kind of breaks from this binary notion of heaven and hell. And so that means that the moment she achieves that full glow, she feels the loneliest.

That radiant glow is a striking image, especially when we first see it on a dog. How did you approach creating this effect?

TGB: We knew we wanted to have practical elements to create the spillover around the glow. So we wrapped both the dog and Mónica in LED strips that had a particular colour and in post-production we would kind of fill in the space where they needed to be. But we wanted to keep the surrounding areas very naturalistic. That was important to me.

I was very much inspired by Post Tenebras Lux, directed by Carlos Reygadas. And I remember the feeling I got from a scene in which this demon was very present, casting a red spill over the hallway. And that was a constant reference for me because it felt so true and sort of quiet, which made it even more special.

It does feel naturalistic and even minimalist for the most part. What was your approach to this combination of special effects and understated style?

|

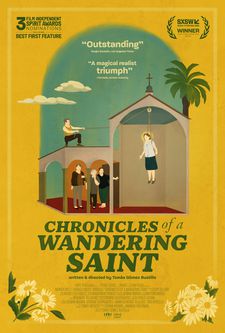

| Chronicles Of A Wandering Saint Poster |

Chronicles Of A Wandering Saint is produced by Plenty Good, your own production company. What prompted you to establish it in the first place?

TGB: It really began with a group of friends from film school. We started workshopping each other's scripts and supporting each other. And then, at some point, we brought people in who could invest and started to think about establishing a system for supporting our ideas, making sure they were both kind of wild but also worked for an audience. That’s how we started. And when it came time to make a movie, it made total sense to do it with my friends and the people who I trust the most.

Would you advise young directors to establish their own production company?

TGB: Rob Spera, a teacher of mine from the AFI would always say in class: if you want to go fast, go alone, if you want to go far go together. And filmmaking is so much about the people that you're surrounded by. And I think when you have people that you trust and people that want to support you but also challenge you, it's important to stick with them. Because at the end of the day, it's not going to be somebody from above that helps you out, it's going be the people that you grow up with.

What future projects can audiences look forward to from Plenty Good?

TGB: Our next movie is directed by my friend Samir Oliveros and it's called The Luckiest Man In America. It stars Paul Walter Hauser, Walton Goggins, Johnny Knoxville, and Maisie Williams. An incredible cast. And they will be hopefully premiering later this year. So be on the lookout for that. It's a game show heist film, a very exciting one. And it just feels like another step forward for us.

Chronicles Of A Wandering Saint is on release in the US now, expanding to LA and Seattle on July 5 and then San Francisco on July 19.

Watch the trailer