|

| Uncropped |

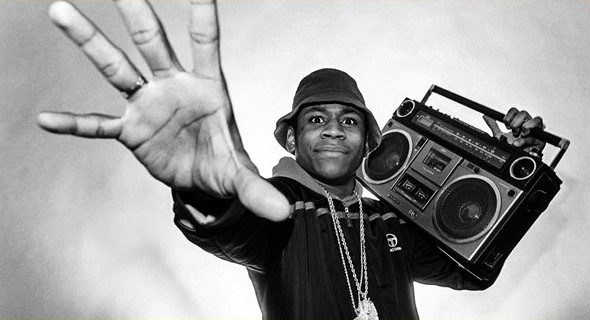

Director DW Young's Uncropped rediscovers and re-evaluates the photography of James Hamilton, who for over four decades worked as a staff photographer at Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Observer and The Village Voice, among other publications.

Hamilton's breadth of work covered street photography, photojournalism, and film set photography for George Romero, Noah Baumbach and Wes Anderson. In his career he has photographed a who’s who of creative heavyweights: Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alfred Hitchcock, Isabelle Huppert, Cary Grant and Liza Minnelli. His photojournalism saw him travel across the US, his images bringing to life the words of the investigative reporter in exposing the interesting side of America and documenting the horror of international theatres of conflict.

In conversation with Eye For Film, Young discussed his disinterest in biopics and Hamilton's cinephilic knowledge. He also spoke about creating an historical document and his hopes that Uncropped will not be described as nostalgic.

Paul Risker: How familiar with James’s photography were you before beginning work on the documentary and what compelled you to decide to tell this story at this particular point in time?

DW Young: When you start a documentary you don't know how long it's going to be, right? That's the first thing. I'm not the kind of person that naturally likes to do things that are long and drawn out, but that's unavoidable for a lot of documentaries. This one wasn't anything crazy, but it was still a long process.

I knew James's work a bit, but our producer Judith Mizrachy was the starting point for the film. She and I work together a lot, and we're also married. She had worked with James long ago at the New York Observer for a year or two when she was the photo editor. So, she knew James, she knew his work, but primarily from what he was doing at that time with her. She wasn't really aware of how much he'd done for the [Village] Voice in the Seventies and Eighties, and the other publications and all the set work.

Fast-forward to Covid lockdown when James joined Facebook to relieve some of the isolation. He started posting a lot of his older work he'd been digitising and archiving with all that extra time for a close circle of friends. Judith was starting to see a lot of that work and was blown away. She started to discover how extensive it was and how it took on different forms. She showed me some of it and I had a similar response. I connected with it on a number of levels - I liked the humour; I liked the composition, but the versatility of it was also remarkable. I thought, "How is it that he's not a much more well known and celebrated photographer these days?"

Sometimes, doing too many things works against you because you're not easy to define. I think his moment in this other era, when millions of people saw his work in these publications, for the most part wasn't digitised and isn’t available anymore. It felt like a starting point, and it seemed like his work needed to be re-evaluated and re-discovered.

Judith and I talked about what it would be like to make a movie, but we were weary of making a photography film or a biopic, two things I wouldn't normally do. They’re done a lot and photography is something general, it's like a sub-genre. So, what to do to make it a movie? Just how does it turn into a movie that I'd find interesting to make?

We met with James and that was the clincher because we got along well immediately and I listened to him reveal the details of what he'd done - the photojournalism, his ethos and the people he'd worked with. I was interested beyond just being a fan of the work, and what it meant as a potential movie worked for me so much more.

PR: You used his point of view to explore American culture across the decades through his work, that still allowed you to get under his skin in a personable way. It strikes me how Uncropped is layered instead of adopting a dominant approach or perspective.

DWY: The more layered the film is, the more appealing it is to me. It's true of a documentary that treats a lot of its elements, the historical and aesthetic and all these other things, to create greater density and a more complex appreciation of what's going on. This is the challenge and that's what I'm usually after.

I'm not comfortable with the idea of making a biopic where you get into someone's intimate nooks and crannies because it's just not me. I don't think James wanted that either and that put him at a level removed from that kind of biopic.

The film first and foremost is about James's work and photography, and the idea that he's this visual portal, but also a personable one too, with his personal experiences through all the collaborators and people he still remains friends with. The photos themselves intrinsically embody this and there was a visual narrative he would provide that would cross into many arenas that allowed for us to do a lot more, which was compelling.

PR: A pleasant surprise was discovering not only how much of a cinephile he is, but the interactions with the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and George Romero.

DWY: It makes the movie a lot more fun because we could talk about movies all the time. I learned a lot, especially in certain film arenas. He knows a lot of stuff about film noir and movies from the Forties and Fifties.

At the very beginning, the idea of making the film almost focused on the set work had a certain appeal. Obviously, the most important aspect of his work and the bulk of it is street photography and photojournalism. That had to take preeminence, but to be able to include what we did and sneak in the cinephilia because it factors into the work and his relationships with people.

He and Mark Jacobson, the writer, talk about films all the time too. If they were off on the road in Texas doing stories about the strange corners of America in the 1970s, I know they were talking about films the whole time. They grew up in a time when movies were so exciting, and people went to see movies constantly. There wasn't that much competition for the experience of what movies offered then.

I loved that James was a photographer because you hear film cinematographers being influenced by photography for their look or certain aesthetics, but you don't hear of photographers being influenced by cinema so much. Black and white filmmaking, above all, and film noir were things that James soaked in early, and loved and continues to love. You can feel it in his work in different ways.

PR: The writers talk about James's photography with great respect, and he reciprocates, emphasising the importance of their words. Uncropped offers an appreciation for the way images and words complement one another - words help guide the images, and the images help bring the words to life.

DWY: That was something, generally speaking, we wanted to achieve. It stems from James's relationship with those writers. Photographer Sylvia Plachy had that same relationship with some other writers, but it was an unusual thing, and I don't think it's that common for photographers to work so closely with specific writers over and over again on long investigative pieces. And it appeared they both felt the complement of those two elements was very important to each side. So, those relationships embody what you're talking about, and they were allowed to present them that way in many cases. It made sense to get that across.

PR: Recalling an earlier point you made about how too many things can go against you, maybe there's too much emphasis on being specific and not enough appreciation for these broader choices.

DWY: He didn't start until he was a little older and he didn't have formal photography training - maybe at that time most people didn't. I do think that often, a lot of young formal training in an art form or medium is a negative thing. I didn't come to film until I was much older and was involved in other things artistically and aesthetically. To me that was a good thing because I didn't feel bound by pre-conceived notions and tendencies that were baked into me. With James, just that idea of working freely and not being worried too much about what it means, who it's going to, and as you see in the movie, he was in a rare position to do this.

PR: Some film production classes teach students that there are methods to making a successful film. Yet you watch films from the Fifties through the Seventies for example, when they were ripping up the book and trying things.

DWY: Well, it's the worst thing in the world because if there's any one truth about filmmaking, is that there are no rules. There are conventions and these things we know work. I think it was someone that had never made a movie before, and they asked David Lynch because they knew him, about eye lines and the 180-degree rule. "Do you have to do that every time?" And he said to them, "No, you don't. You can do whatever you want, but it'll be hard to cut if you don't."

PR: The interesting thing about cinema is we forget that it's still in its infancy. We're yet to explore the limitations of the medium that's still in an experimental phase. The commercialisation and business aspects however pose certain challenges.

DWY: Yeah, that's the big one. Cinema has to reckon with not being the dominant form of the moment anymore and what that means. That ties into the commercial too. So, that's a tricky thing.

PR: Listening to James discussing films, you get a sense that cinema was a more dominant art form, which provokes a feeling of nostalgia.

DWY: There's an unavoidable nostalgia, but I wouldn't want to think of it as a nostalgic film. It's hard to discover films like you used to because you read about them in advance online. You, of course, always have a preconceived notion based on where you're seeing it or any number of factors, but you used to not know anything about a film when I was a kid. There were no looking things up online; you happened to go into the theatre to watch something, and you'd be going in cold half the time. And that was great because it can go either way, but that's when you have revelations about films.

PR: It's fitting that our conversation drifts in and out of cinema, given his cinephilia. However, the work of James and his colleagues recorded important domestic and international news stories, yet so many of these publications were not digitised, meaning the words and images are lost to the past. It makes us contemplate the impermanence of it all, and how we're missing much of what was recorded in the moment.

DWY: … Part of the desire of the film is to provide a record of those times and the publications, so they can be referenced and understood, and they will not be lost in time. The values and a lot of what they had to offer can be revisited. Alexandra Jacobs says in the film that a lot of the stuff that was written might not last because it was written in the moment and there was no perspective yet. Still, that original source is important and often some brilliant things are written in the moment that shouldn't be forgotten. She says James's photography is going to last and that's also the beauty of photography. It's not that context isn't helpful, but so much of it doesn't need context at all. You don't need to know, the photo stands alone extraordinarily well for so much of his work.

Uncropped opened theatrically in NY & LA on 26 April and launches on Digital 7 May.