The Forest Maker (Der Waldmacher) from director Volker Schlöndorff is an evermore important film essay on the decades-long work of Australian agronomist Tony Rinaudo with African farmers and the community at-large. Idriss Diabaté from Ivory Coast, Senegal’s Alassane Diago, and Laurene Manaa Abdallah from Ghana are credited as co-directors and provide us with vital insights in their own individual sections.

“Nothing is lost” Rinaudo says and everything can be regrown again. Angela Winkler, star of Volker’s Oscar-winning adaptation of Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, lends her enchanting voice to the prologue, which recounts an old African legend about the cradle of mankind, as collected by Carl Einstein.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff with Anne-Katrin Titze on Sebastião Salgado: “He himself restored his forefathers’ land in Brazil. So he knew exactly what this was about.” |

There is at the very start a quote by Richard St. Barbe Baker, from Tony Rinaudo’s favourite book since his youth, I Planted Trees from 1943.

TS Eliot in The Waste Land, which turns 100 this month, writes:

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief, And the dry stone no sound of water. Only There is shadow under this red rock, (Come in under the shadow of this red rock), And I will show you something different from either

And indeed, Tony Rinaudo does show the world something different, namely a subterranean system of roots, what he calls an “underground forest,” which can be tapped into, because nature has the power to heal itself.

Schlöndorff calls his documentary a essay as it contains a number of different approaches to the vast subject at hand. From sandstorms to population growth, from methods of harvesting and bad agricultural decisions in the past to the attempts to build the “great green wall” across the continent, to Sebastião Salgado’s shocking famine photographs - there is a lot to explore.

The stump of an old tree that used to house the resident snake has been the sighting of a ghost. Ancient storytelling traditions speak of the spirits of the earth. Maybe they lie dormant, nestled in the underground trees, waiting for humanity to get a grip on their greed.

From Berlin, Volker Schlöndorff joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on The Forest Maker and Tony Rinaudo.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Hi Volker!

|

| Volker Schlöndorff with Tony Rinaudo: “I hired a local cameraman and a local sound man, doing the second camera myself.” Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

Volker Schlöndorff: Hello! Beautiful, how are you, Anne-Katrin?

AKT: Fine, how are you?

VS: I’m great, you got nice flowers there!

AKT: Yes, lots of them. They are from my farmers market. There is an Amish stand and they have the most beautiful flowers. I always get them and their blue eggs.

VS: Great, is that a yellow rose?

AKT: It’s not a rose; I don’t know what flower it is. Let me get them closer.

VS: Ah, I see what it is. I don’t know what it’s called, but it’s beautiful. I am really looking forward, this is, I guess the first trip in three years now to the US, because of the pandemic. So I’m looking forward to finding all my friends in New York and also in the Hamptons, of course. I’m very happy with this little documentary, which turned out to have a certain importance at least. Because of the cause. This is more activism than art of cinema. Even though I’m very happy with the form it took, half documentary, half personal witnessing basically.

AKT: You call it a film essay and list “Co-Regie“ [co-direction] with three African directors who have their own smaller sections. I thought the beginning was very beautiful and artistic because there are so many things going on simultaneously. There is the very start with a quote by Richard St. Barbe Baker, whom I did not know.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff filming Cecilia Topok Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

VS: That was Tony Rinaudo’s favorite book, and it was his revelation when he was, I guess, 14 years old. And it is still so valid, even more so today than in the Forties when it was written.

AKT: It sets the tone. When the forests go, there comes the famine, the pestilence. A small step to Covid, there’s everything.

VS: Everything is there.

AKT: Is that the actual book we see where he underlined certain phrases?

VS: Yes, absolutely. Let me get it. [Volker holds up the book] I’m the one who underlined it. This is it indeed. I found it online, an old edition, and it’s inscribed with love and best wishes by someone in January 1947. It could almost have been the one that Tony had in his hands.

AKT: That’s what it felt like. And then, to go on with how beautifully you set up the beginning, in comes Angela Winkler! Her prologue has a tale-telling quality; she has such a wonderful tone of “Now children, I am telling you how it all began …”

|

| Volker Schlöndorff with Anne-Katrin Titze holding up I Planted Trees by Richard St. Barbe Baker |

VS: I only recorded it once on my iPhone in her kitchen. And she hardly knew what she was reading. I mean she read it through once silently and then we recorded it immediately. I thought this was good for a layout, and after the film was finished editing and we got to the sound mix, I tried to do it again with her in a studio to no avail. We never found that tone again.

AKT: What is it exactly that she is reading?

VS: This is an African legend as collected by a German anthropologist by the beautiful name Carl Einstein. He was the first one to write about African art, the kind of abstract Cubist description of African statues. That book was read by Picasso as well as all the group who went into this. Collecting the stories was more a side occupation of his. He was mostly in African art and what then became abstract art.

AKT: The title The Forest Maker sounds even more mysterious and ominous to me in German - Der Waldmacher.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff on Tony Rinaudo: “They’ve known him for almost 40 years now but he wasn’t back in the last twenty years or so, but they recognise each other.” Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

VS: I didn’t invent that word. Tony for ten or 20 years already goes by the nickname the Forest Maker. He wrote a book, there’s been a new edition this year, and it’s called The Forest Maker. I simply kept this title. I don’t even really like it because it’s so misleading.

It is not about forests, it’s about trees; a number of trees per acre so that they can do agriculture underneath the trees, that’s the idea. It’s to make possible the so-called agroforestry, which is the ancient way of cultivating in Africa. Because it was always too hot to do it in plain sunlight. Also because of the sandstorms the trees were absolutely necessary. The Forest Maker sounds good but it’s misleading.

AKT: Well, it’s also referring to the forest underneath.

VS: That is a word that he [Tony] coined. He is, you see, besides a good agronomist, he is a very good communicator.

AKT: And he is being greeted like a rock star when he arrives.

VS: Yes, at least in the Sahel villages.

AKT: I liked that you chose to film these meetings and how outspoken some of the local women are about what is going on.

VS: They’ve known him for almost 40 years now but he wasn’t back in the last 20 years or so, but they recognise each other.

AKT: You include the Sebastião Salgado photos, the horrific images of the famine of ’84, ’85.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff filming a Tony Rinaudo conversation Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

VS: [getting his Salgado book] I can almost document everything we are talking about. I’m very grateful to Salgado because usually you can’t even pay the license for these pictures and he gave it for a minimal amount because of the cause. Because he himself restored his forefathers’ land in Brazil. So he knew exactly what this was about

AKT: There is Wim’s great film about him. I did an introduction to the film at the IFC when it came out.

VS: Oh you did?

AKT: Yes, it’s a fantastic film, I think. It’s good that you connect so many things in your film, from the Great Green Wall to the constant shifts that are happening.

VS: In a sense that’s why I called it an essay, which means it’s a tryout. I was trying to make a documentary. Going into all directions without any preconception after having met Tony in December of 2018 in Berlin after he got this Alternative Nobel Prize and spoken to him afterwards. Six weeks later I was already meeting him again in Bamako, Mali this time and I just started shooting without any idea what was going to come up. And I maintained that attitude.

I hired a local cameraman and a local sound man, doing the second camera myself. This turned out to be such a winning formula that I replicated it wherever we went. Having a local cameraman had the advantage that he spoke the language of the people in the villages we came to. Some were better camera men, some less so. I was the constant anyhow. We were not really visible as a movie team. It was two Africans and me and on the other side Tony and his African collaborators, so it was very low-key which allowed the intimacy we established.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff on Anne-Katrin Titze’s Green Market Amish flowers: “I’m great, you got nice flowers there!” Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

I didn’t know anything about trees but I knew I wanted to give a different image of Africa from the one prevailing in the audience’s mind in general, because for 14 years now I’ve been engaged in the humanitarian sector in Africa and in the educational sector because 14 years ago I helped to create a small film school, I’d rather call it media school, in Kigali, Rwanda, where we do documentaries and small TV series. Almost to be seen on your cellphone, ten-minute segments, which is the only way to communicate in Africa.

AKT: In the context of Ukraine, Africa has been in the news …

VS: … but that is again because of the mistake! They had their own crop like millet and cassava. In the Seventies we started to export our surplus of wheat and got them used to white bread and to baguette and toast. That wheat doesn’t come anymore now. They made themselves dependent on us or we made them dependent on us somehow. It’ll be a hard way to come back to their proper crops. But it is unavoidable, because otherwise they die of hunger. As Tony says, there is nothing like a good storm, a perfect storm to change people’s attitude.

AKT: Look at the mistakes in farming all over the globe that we are now confronted with! The local grains are millet for Africa, the wheat in Europe, the rice in Asia, and the corn in America.

VS: This is where the local filmmakers came in. I asked them to contribute something to the film and said “your voice would be far more authentic than mine.” This is how one said “I’m working on millet. I’m advocating the reintroduction of millet and nobody wants to listen to me.” He used the opportunity because very few of the African filmmakers get the necessary exposure in festivals, especially with documentaries.

AKT: What is his name?

VS: Idriss Diabaté from Ivory Coast. The other one, most stunning is from Senegal, called Alassane …

AKT: … Diago?

|

| Volker Schlöndorff and Tony Rinaudo talking with the farmers Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

VS: Yes, Alassane Diago. He did this thing about his mother and his sister in the village where no men are left. Of course there is this almost archaic moment when his mother takes out the gown, his father’s dress. His father whom he hasn’t seen in 30 years. Nobody knows if he’ll ever come back. These are jewels in the film, which I could never ever have done myself.

AKT: It’s one of a number of phantoms in the film, the father’s ghost. At another point there is mention of one tree that had a local snake and then a ghost appeared.

VS: I knew a bit about Africa but I had only been in the cities, never really to the countryside and certainly not as deep into the countryside as with Tony. You feel that everything is inhabited. It has nothing to do with animism. No, it’s one monotheistic religion all over Africa, even though it may be Islamic or Orthodox or Christian or whatever.

But nature itself - every tree and every river has a spirit or a soul or something; everything is inhabited. The spiritual and the materialistic are completely interwoven and that had to go into the structure of the film that I had to open beyond agriculture into these beliefs. Even the fight for a different form of agriculture, education, family planning - all that can only be achieved in Africa if you include the spiritual dimension.

AKT: Even that of the objects. I think it is Cecilia Topok, the farmer, she has this very sophisticated water setup and fantastically constructed objects.

|

| Volker Schlöndorff filming the farmers Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

VS: You mean those to brush your teeth?

AKT: Yes, all of that looks very creative.

VS: That is all over Africa the system. If you don’t have running water you have to carry every drop of water for your household first on your head. Then you have to have this ingenuity to invent a simple system to have running water.

AKT: It almost feels alive, as though there were a water spirit in this construct.

VS: She is my favorite character anyhow. I first met her, actually each time without Tony, at the time he was in the hospital with malaria. Once you had it, it always comes back. I was blessed that I never had it and didn’t get it. Anyhow, after I spent a day with Cecilia, I saw her at several public reunions. She’s so very outspoken. Then I asked another filmmaker, she is working at the film school in Accra. What’s her name? Laurene.

AKT: I have it here, Laurene Manaa Abdallah.

VS: Exactly. So Laurene with a small crew from her film school went all the way up from Accra to where Cecilia lives, which is two days by car. They spent a week with her. I had given her a list of things I was interested in because of just that one long interview I had done with Cecilia about her life. That’s why we had so much material with her; I even had to use it in the prologue. I mean, that’s how the prologue came about.

AKT: Nothing is lost. Give nature a chance and it will heal itself. These are very optimistic and important messages.

VS: And it doesn’t need all that much money. It just needs the money to help the farmers to get over the period of growth, which is something between five and ten years, before it is stable enough to do agriculture on these grounds. I mean, they can always do a little, but they’ve got to protect the growing trees from the animals and also from mankind who come to cut them down.

AKT: Yes, mankind. Yesterday in my fairy tales and storytelling course we discussed Philipp Otto Runge’s The Fisherman and his Wife from the Grimms’ collection. It’s 1812 and the ocean is revolting because of sheer endless human greed. And there are my students looking at it saying, well this is a description of climate change. Then came the question, why doesn’t the fish stop it? Well, the fish can’t stop it. We can.

VS: Yeah, I forgot. I know the story well. Günter Grass used to quote it when he did The Flounder, of course. I didn’t think of it in that context. It’s astonishing how even in Europe there were periods of time between 1700 and 1800 where there were barely any forests left and there had to be a real campaign at the time by the feudal forces to reforest Europe. It is an ongoing struggle. Around the Mediterranean basin there are no forests anymore because the Greeks and Romans cut them down to build ships. But they could also be regrown.

AKT: This is really fascinating.

VS: Actually, I was with the film on a Greek island which last year had such fires that 100 people died, and the Thessaloniki Film Festival created a small one-weekend festival to re-encourage the locals not to give up and that they could reforest their island. The film was totally appropriate almost as if it had been done for the opportunity.

|

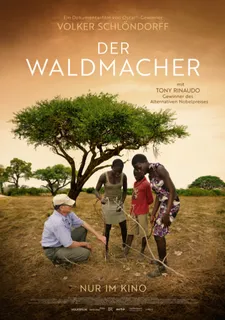

| Der Waldmacher poster |

AKT: Wow! You are touring now with the movie?

VS: I’m a traveling salesman with the movie. Because all over Europe moviegoers did not come back to the theaters yet. It’s between 40 and 60% less as compared to before the pandemic, especially I’m talking of the art-house situation. And it’s even worse for documentary films. So to get the film out there, I decided with the distributor that I would go everywhere, meaning literally almost everywhere.

Of the 88 still functioning art houses in Germany alone, I visited 44 on the first trip for five weeks, crisscrossing the country by car, sometimes two cinemas a day. And festivals, lately in Jerusalem or in La Rochelle or wherever to promote not so much the picture, but to encourage cinemas and cinema goers and to do a little activism about environment.

AKT: A good combination.

VS: We always had a full house because the audiences, if there is an event where an actor or director shows up, they show up too. Next week I’m traveling with Tony to Paris and Brussels to talk to politicians as well as to regular audiences. Therefore I’m very glad I also got a foot in the American door with a small showing at the Hamptons Film Festival. Over here, the result is that Amazon got interested in the film and picked it up for some European countries. Basically, I’m back at the Lunar Park level of filmmaking, I have to show up in person everywhere. “Come on in, come on in, you’ll see things you’ve never seen!”

AKT: That’s great, though. A return to the beginning of cinema at the “end” of sorts of the pandemic. I’m curios, on your road trip, did you discover a new favorite little art-house cinema in Germany?

VS: Well, there’s one that has the beautiful name of Liliom, in Augsburg of all places, Brecht’s town, it’s gorgeous. In Frankfurt is one called Harmony. I could name a few more because they became very dear to me. I’m so popular with the art-house people now that their association is giving me at their annual convention in Leipzig an award for myself and another one for the movie.

|

| Tony Rinaudo with Volker Schlöndorff and the film crew Photo: courtesy of Volker Schlöndorff |

AKT: Great! You mention Augsburg, did you by chance go to the cinema in Schrobenhausen, the asparagus hub and Lenbach town?

VS: No, near Schrobenhausen. I was in Dießen on the Ammersee. Some are ailing and have the feeling they have to give up. Is the time of art houses over? I say no. But a lot of them are giving up. That also goes for Italy. I was in places in Italy and Spain and elsewhere. Even in France it doesn’t look so good.

AKT: We’ll see. Maybe it’s like the trees.

VS: Absolutely!

AKT: The cinemas have to grow back

VS: Reforest the cinemas!

AKT: Volker, thank you for this!

VS: You’re very welcome, thank you for your interest. I’ll call you when I’m in New York!

AKT: Looking forward to seeing you soon!

VS: See you Anne-Katrin, bye bye!

The Forest Maker screens at the Hamptons International Film Festival on Friday, October 7 at 4:00pm - East Hampton; Saturday, October 8 at 5:45pm - Sag Harbor. Volker Schlöndorff will participate in Q&As on both days.