In the second instalment with Dagmar Schultz, the director of Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992 we discuss James Baldwin, Audre Lorde countering fears, experiencing difference in a positive way, looking at what you do, a creative writing workshop at the Freie Universität in Berlin, poetry becoming part of your life in a useful way, and more.

In 2021, Hunter College hosted during the spring semester an “Audre Lorde Now Series”, a public program of four online events: My Words Will Be There; Doing Our Work: Confronting Racism - and Other "Isms”; There Is No Separate Survival: From Divide And Rule To Define And Empower, and Self-Care As Political Welfare. In the fall during the 20th edition of DOC NYC, Hunter’s MFA Integrated Media Arts had five filmmakers, including Neville Elder, Lidiya Kan, and Kim Maxime Baglieri featured in DOC NYC U.

|

| Dagmar Schultz with Anne-Katrin Titze on Audre Lorde: “She made the effort to convince women and make them feel how important it was to experience difference in a positive way.” |

Audre Lorde (1934-1992), poet laureate of New York from 1991 to 1992, won a National Book Award, received honorary doctorates from Hunter, Oberlin, and Haverford colleges and a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. She taught at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and Hunter College and her remarkable civil rights activism touched many around the world. Dagmar Schultz was the one who invited Lorde to come to West Berlin in 1984 for a visiting professorship, which began a long and close relationship and mentorship with a number of movements in Germany.

From Berlin, Dagmar Schultz joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on Audre Lorde and Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992.

Anne-Katrin Titze: A line that Audre Lorde says in your film stays with you - “We were never meant to survive.” It is powerfully countering the fears.

Dagmar Schultz: She really felt that. For one thing, colour is the bottom line and that for Black people in the white man’s society, especially Black women, they were not meant to survive. Or that nobody cared whether they survived. It meant you had to get yourself together and come together to even make it in the society in one way or another. She made a lot of effort with white women, she was not somebody who said “Well now I’m here and I’m focusing on my relationship with Black women. At her readings, the majority were white women and it wasn’t always easy, the discussions were quite heavy.

|

| Dagmar Schultz with Audre Lorde in 1986: “We have some power and we need to look where is that power? And how can I use it?” Photo: Dagmar Schultz |

She had to deal with things she would not necessarily have to deal with in the United States, because there’s much more of a discourse on racism than it was at the time in Germany. But it was quite admirable. She made the effort to convince women and make them feel how important it was to experience difference in a positive way.

One thing that was for me always important that she said: “we all have some power.” Whether we are Black, whether we are white, even it it’s just a little bit, but we have some power and we need to look where is that power? And how can I use it? Because if we don’t use it it goes to waste or it’s going to be used against us. That was a really important message for many people here. Because people can, in an increasing way, feel helpless, considering globalization, political situations and thinking I can’t do anything anyway. So it’s important to look at what can I do.

AKT: And precisely to use difference in a positive, creative way. For centuries we took from what was there. We took from Tennessee Williams …

DS: Yeah, yeah.

AKT: We took from Faulkner, from Hemingway - except the bullfight stuff, that I throw out right away. I love what Audre said about poetry, which you emphasized in the film. She calls poetry “the most subversive use of language” because it “attempts to bring about change by altering people’s feelings.”

|

| Audre Lorde with Ika Hügel-Marshall, co-writer of Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992, Berlin 1991 Photo: Dagmar Schultz |

DS: Feelings, yeah. She was very convinced. For her poetry was like an essence of her life. She considered herself a poet before she would consider herself an essayist or novelist, even though she was a very good essayist and she did write a novel. Half of another one is unfortunately laying there unfinished. Poetry was for her, as she once said, “the skeleton of the architecture of her life.”

Or as she said, it’s a weapon for her to use. I took part in one of her writing workshops here in Berlin, and that’s what she communicated. How poetry can also be a woman’s weapon. When Virginia Woolf said, you need a room of your own, but many women don’t have a room of their own. And she said a poem you can also write when you’re a nurse and have just a ten-minute break. There are ways in which poetry can become part of your life in a useful way.

AKT: Was that the same workshop someone in the film, I think her name was Traude Bührmann, talks about? She mentions that the only ones there thrilled by the poetry were the people writing it. The difficulty of writing poetry! It’s not “just poetry.” Most poetry doesn’t change people’s feelings.

DS: That’s right. Yeah, that was that workshop. Actually it was the first time a creative writing workshop was taught at the Free University. In Germany, even though we call ourselves the country of thinkers and poets, writing is not taught at universities, I mean creative writing.

|

| Audre Lorde at the John F Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Freie Universität in Berlin 1984 Photo: Ute Weller |

AKT: Apropos, there is a moment when we hear “you look back at 400 years of slavery, and I ask a white German woman to look at one generation and it’s too much.” German history is also very much a part of her conversation.

DS: Yes, and you see that in the Audre Lorde online journey. She went to this one memorial in Berlin, which is n resistance against fascism. It has a big urn, like a vase, that says “This urn contains earth from concentration camps.” She went there and she wrote this poem.

For her, how people dealt with anti-Semitism, after being at that place, she said “I can understand now why my students consider National Socialism a terrible event which you rather want to forget about and don’t want to deal with.” For her that presence of German history, in Berlin especially, was very strong. She dealt with that in a lot of ways.

AKT: I remember talking to Amma Asante when she was preparing her film [Where Hands Touch] about the experience of a Black woman in Germany during the Third Reich. Did you ever see it?

DS: No, I don’t know it.

AKT: What you show of Audre are really personal moments. We learn how much she enjoyed dancing, parties, ice cream …

|

| Audre Lorde with May Ayim, Rakibe Tolgay, Ariane Mondon, Katharina Oguntoye, Ika Hügel-Marshall, and Dagmar Schultz in Berlin 1990 Photo: Dagmar Schultz |

DS: … sausage! She’s at the market and says “Oh this sausage is so good, I have to get it for Gloria!” But then she says “it’s bio and health food, she won’t like it!”

AKT: Also her insistence on matching pillowcases and blankets because “at night your soul’s eyes open.” We get a real glimpse into a life, totally different from, let’s say, Terence Dixon’s Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris, that was showing at the 2020 New York Film Festival. The film was about James Baldwin’s time in Paris. It is the opposite of what you are doing, the other side of the moon.

DS: I can imagine. This film grew out of friendship and love and movement activities. It’s different from a film where somebody goes to document somebody’s times. [While we talk on Zoom, someone walks by in the background]. That was Ika [Hügel-Marshall], who was sitting there when Audre was talking about the pillow cases! Ika is sitting there [in the film], thinking “Third eye? What is she talking about?”

AKT: What was the connection like between Audre and James Baldwin?

DS: Yeah, they had something that Gloria Joseph organized at Hampshire College. She invited both of them for a discussion. And that’s become quite a famous thing, the talk between the two of them. It has not really been published. Essence had an excerpt of it. There’s something on the Net about it.

|

| Audre Lorde with May Ayim at the Winterfeldmarkt, Berlin 1990 Photo: Dagmar Schultz |

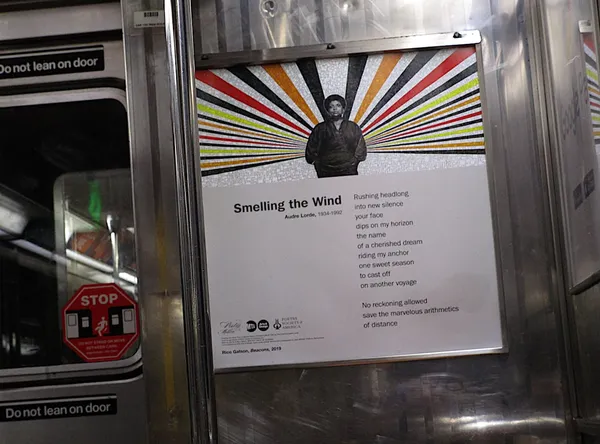

Gloria was going to make a complete manuscript but then unfortunately she passed before she could finish it. The Baldwin family didn’t release it completely. They had a very intensive relationship intellectually and politically. It should be very interesting to get the whole manuscript. And now in New York there are murals at 167th Street [in the B and D southbound subway station in the Bronx] of Baldwin and Audre in the subway.

Read what Dagmar Schultz had to say on being an archival activist and more on her longtime relationship personally and professionally with Audre Lorde.