In the second instalment with Inés Toharia on Film, The Living Record Of Our Memory (a highlight of the 12th edition of DOC NYC), we discuss Wim Wenders’ participation through his foundation, finding Lon Chaney’s The Unknown, the Mostly Lost Film Festival, Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures Of Prince Achmed, Disney and Pixar preserving their films on film, Questlove’s Summer Of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), the USC Shoah Foundation, and a wide representation of film archives and locations around the world.

|

| Inés Toharia on Ken Loach getting coding tape from Pixar: “It was so funny, the correspondence between them. I loved also what he said about light.” |

From Spain, Inés Toharia joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on Film, The Living Record Of Our Memory.

Anne-Katrin Titze: I liked the two times Wim Wenders shows up in your film. I interviewed him many times and we stayed in touch over the years. The first instance in your film with him is about rights for the music, which is the reason why The Goalie's Anxiety at the Penalty Kick wasn’t shown for 30 years. Wim didn’t have the rights for the songs he used, but the music can be changed now. And the second about Alice in the Cities being all scratched up. How did you end up talking to Wim?

Inés Toharia: It was through the Wim Wenders Foundation. They provided the footage they created to show the work of the foundation. So we wanted to talk to Wim, but they said, we actually have this film, and we could license it so you could have it. The film was amazing, it was much longer, of course. With these two fragments we asked, would it be possible and Wim and the foundation cleared it. That’s not something that we shot, but that they provided. We picked the pieces that we used, but I would have loved to talk to him personally, too. He may be very private, too.

AKT: The fact that you talk about archiving all over the world is great. The cinémathèques in Africa, you go to the Philippines, South America - and the film informs us about conservation problems people might not think about, such as humidity and the fact that in India the first three archives were in harbour cities. Was it that one archive led you to the next? How did you move around the globe?

|

| Vittorio Storaro in Film, The Living Record Of Our Memory |

IT: It kind of did, because we were kind of waiting and there was the budget and time, so it was little by little. And then of course the pandemic came up and some things we hadn’t shot yet we had to give up. Fortunately we had almost everything we needed. I think all in all, there’s a wide representation of archives and locations. Because it was really important to show that it’s all around the world the same problems, same issues, but of course humidity is different in different sites of the world.

AKT: I learned so much that I didn’t know before. Also the great little anecdotes. For instance how the Lon Chaney film The Unknown ended up as missing because it ended up being stored with the unknown titled movies! The Mostly Lost Film Festival - I had never heard of it before. You went to it and filmed there?

IT: I filmed just after the festival had taken place. They gave us the footage of inside the cinema when they were discussing that from TCM, the channel. But we filmed the theatre empty and the theatre outside when we visited the Library of Congress. The festival was just over, which was good, so they could show us all the paper prints and we could shoot while they were more relaxed than during the festival. They have it every year and most archivists know about it and they tell us stories about how they discovered this or that. The detective work that you were talking about.

|

| African Film scholar and film program curator Aboubakar Sanogo in Film, The Living Record Of Our Memory |

AKT: You have a clip from The Adventures Of Prince Achmed, the Lotte Reiniger film from 1926 and a little snippet showing her. Many people think Disney’s Snow White from 1937 was the first animated feature-length movie. No, there was Lotte, eleven years earlier! On the other hand, we learn that Disney was the only studio that was archiving and taking care of their stock from the start while other studios were actively destroying theirs.

IT: Yes, and they still preserve it on film too, which is a good idea. It’s Steve Bloom, the editor of Pixar Animation Studios, who reminds us that it’s kind of ironic that now that we shoot and post-produce and even project digitally that they save digital materials by passing everything onto photochemical film back again and that’s what they preserve in film archives. In our times it’s going so fast that digital materials, they don’t last, they have to be migrated every five years.

So yeah, Disney or Pixar, they are preserving their films on film, the new titles and they are of course keeping the originals. Pixar, which is a digital studio, and other big studios too, they preserve on film. It’s very expensive, but digital is also very expensive.

AKT: It’s fascinating and a bit scary in the end. People often think of the opposite, that if something is out there digitally, it will always be out there. And the people in your film make very clear statements, that no, this is not the case. Did you know all of this beforehand?

|

| Decomposing Nitrate Film at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam: “Knowing what we’ve done in the past that’s really horrible and not to repeat it …” Photo: Eye Filmmuseum |

IT: Although I make documentaries, I love found footage and discovered the field of preservation from that. I studied film preservation, that’s how I came to know the people in the field better. I went back to filmmaking but kept in touch, because I admire so much the people. I kept thinking, wow, nobody really knows what they’re doing.

They are the unsung heroes behind the stages of film history. It’s thanks to them that we have access to history. Even for instance, [Questlove’s] Summer Of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), the documentary. An archivist found this footage. We all know about Woodstock, but Harlem in 1969? We can all now discover and enjoy that and think more about our past. It takes one person. I was fascinated by these people who are so dedicated.

AKT: It is our memory, as your title states. And with newly found footage the memory changes and shifts. It’s very important that you include in your film the USC Shoah Foundation, and footage discovered from the camps, the Great Depression, genocide, horrors committed. Without that anything is possible. But back to Pixar for a second, I love the anecdote about Ken Loach and his getting the coding tape from Pixar.

IT: I love that too. It was so funny, the correspondence between them. I loved also what he said about light. What you were saying, it makes us think. And knowing it so directly. Knowing what we’ve done in the past that’s really horrible and not to repeat it and to realize that this has happened and this is man-made, human-made. To evolve, I think it’s crucial, the use of film and the importance it has.

|

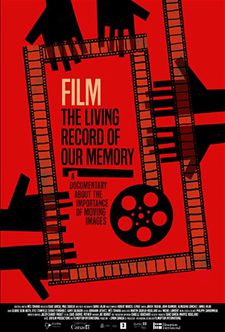

| Film, The Living Record Of Our Memory poster |

AKT: The enlightenment in the light. The moment when the man speaks about seeing the footage of Chile, September 11, 1973. He recounts his childhood memory of being happy that he didn’t have to go to school that day of the coup d’état. I noticed my heart began beating faster seeing that clip. I felt a strong physical response to it. It is really the memory of the world that can be transmitted through images entering the body. It’s very powerful, this thesis of your film.

IT: Thank you, I’m very glad that you saw that. Because when I was working on that, whenever I saw those images, I thought, I’ve seen it again and again and I felt it in my gut, even in editing. I had seen it again and again and it still happens to me. And you are seeing someone who has seen images and realizing what they didn’t know. And you witness what they witness what happened.

AKT: The other moment that touched me deeply was at the end with one of the kids in distress. I love that you end with children because they are the future; ultimately, it’s all for them; all the archiving is for the little ones. The last one flies a kite.

IT: Yes, in the end, even if it’s destructing, it’s important to realize and remember that the footage is there and the images are there and they transmit things and we learn from it. I had the idea from the beginning that I have to use some footage that is a little window also. Because our journey is to open windows. Remember the last quote? Yes, film is a window so we learn from each other, we can see and keep seeing things.

Read what Inés Toharia had to say on an Orson Welles quote, Henri Langlois rescuing FW Murnau’s Faust, Duyu Dan’s Pan Si Dong (Journey To The West, 1927), the inspiration of Jonas Mekas, Pan Nalin’s Last Film Show, and Martin Scorsese’s crucial role in preservation through the Film Foundation.