|

| Cunningham director Alla Kovgan on Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage: 'In a way they are timeless' Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

In the second half of my conversation with Alla Kovgan on Cunningham (read the first half here), we discussed her appreciation for the significant role Derrick Tseng (Todd Solondz’s longtime producer, Life During Wartime, Dark Horse, Wiener-Dog, Palindromes) played in getting the film made, Director of Choreography Jennifer Goggans and Supervising Director of Choreography Robert Swinston and Notes on Choreography, storyboarding for locations in New York and shooting in Germany with Mko Malkhasyan.

Also: The timelessness of the collaborations by Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage and Merce Cunningham and the transcendence of time that Karl Ove Knausgård in My Struggle assigns to works of art as compared to science.

|

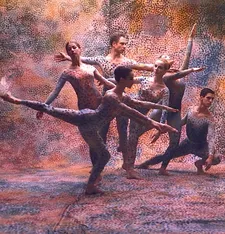

| Merce Cunningham, Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Cynthia Stone, Marilyn Wood, and Remy Charlip in Summerspace Photo: Robert Rutledge |

Cunningham has a flawless score by Hauschka aka Volker Bertelmann (BAFTA and Oscar-nominated composer with Dustin O'Halloran for Garth Davis’ Lion) and stereography by Joséphine Derobe (Wim Wenders’ Les Beaux Jours D'Aranjuez, Everything Will Be Fine) that takes us creatively into the world of Merce Cunningham.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Your producer Derrick Tseng is also the producer of Todd Solondz’s films.

Alla Kovgan: Exactly. Derrick is amazing. He came to the project very early in 2012 and he ended up doing everything, from producer to assistant director to everything. It’s an honour to work with him. In a way, this is an impossible film to make. Because you can’t make a 3D film about an avant-garde American choreographer, costing three million dollars. You cannot in this contemporary environment we’re in. So I think he believed in it from day one. You know, films need money but they’re made by people.

AKT: Your choice was to have the focus on the time from 1942 to 1972. Independently from Cunningham, just to think ’42 to ’72 - everything happened. It isn’t really mentioned in the film, what did Cunningham, what did Cage do during the war?

AK: Well, they were in New York making work. Credo in Us shows up 1942 - it crosses people’s minds - they were doing that in 1942? The whole world was going crazy. Cunningham had this incredible ability to focus on the work. They’ve lived through it all, the war, the Sixties, ’68 - all of it. In the end, as a dancer, you come to the studio and dance where you work. You do the class, you start making movement. You are teaching the movement to others. That’s what I wanted to show. And when he said, “I’m a dancer,” that was the most important thing. That he could concentrate as far and as long as he could.

AKT: Which he could for a very long time, till age 90.

AK: Right. In a weird way he’s a timeless character. The presidents, the war, things come and go. Some things are timeless. They stay. Those people like Rauschenberg and Cage and Cunningham in a way they are timeless.

AKT: The dance is not about anything. It is.

AK: Oftentimes when you look at his notes, you start noticing that you can see what he was thinking about. He just did not want to tell you, or the dancers for that matter, what it is about. He wanted you, based on your experience - whether you could associate it with concentration camps, race riots, the atomic bomb or Wall Street crash - it doesn’t matter. You in the audience close the circle. All the horrors of the 20th century and all the thrills of the 20th century they lived through. Especially John Cage who was also a kind of preacher. He’d articulate things, he was the voice.

People say Cunningham didn’t talk. That’s not true. What I learned is how much he actually talked and how many questions he was asked over and over again. They were always the same questions. The way they lived was an act of politics as much as anything else. This kind of anarchy, everybody is doing their work as best as they can - isn’t that a great way to organise a society? Well it is, if it actually works. I don’t think they were apolitical or not involved with the times at all.

AKT: But transcending time also. I think it was in [Karl Ove] Knausgård’s My Struggle, where he made a point about how 18th century science, we don’t really care that much about and don’t know that much about any more. But the 18th century artworks are still there and very prominent. They touch us, get to us, influence us.

AK: Absolutely.

|

| Wim Wenders' Pina in 3D Photo: Donata Wenders |

AK: It’s about the art. He said basically, “I would like to make art that’s so logical, when you come out you feel happy to be back to life.” It’s so bewildering.

AKT: It makes a lot of sense.

AK: Of course. But a lot of people think of art as something they escape to.

AKT: We also get interesting detailed technical information. Technically, it’s ballet for the legs and modern dance for the torso. You worked with his notes, for the first time. He didn’t share his notes?

AK: It’s interesting what is shared and what’s not. There’s a book called Notes on Choreography. It’s a book that was around since 1968. It’s just a collage of things. We had of course through Robert Swinston and Jennifer Goggans access to his notes about each dance. I’m from Moscow, so for me it was really interesting to see how much Cyrillic was in his notes. I never had an idea that he learned Russian.

AKT: Russian, knitting ...

AK: It builds a personality. You get a flavour of him, of his character from different sides. That was the goal, to also show him as a human being who was interested in things and who was incredibly humanist, I think.

AKT: Some of those locations in Germany looked beautiful. Where were they?

|

| Cunningham opens in the UK on March 13 |

We would think about Merce’s physical questions in cinematic terms. If it’s based on the action of falling, we put it on a rooftop. If it’s based on an idea of layering we put it in the woods and so on. It took a long time, funding wise we had to start in Hamburg and end in Stuttgart and also in the Cologne and Düsseldorf area.

AKT: So the locations are all over the place?

AK: Exactly.

AKT: Not like Wuppertal for [Wim Wenders’] Pina.

AK: No, all over the place. We did shoot in Wuppertal, actually. But we ended up traveling, all within six weeks.

- Read what Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener (dancers in Alla Kovgan’s Cunningham) had to say on the choreography of Merce Cunningham and the 3D for Cunningham.

- Read what Alla Kovgan had to say on Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, Rei Kawakubo, John Cage, Carolyn Brown, Hauschka, and the 3D for Cunningham.

- Cunningham is available to watch in the UK on Curzon Home Cinema