|

| Ira Spiegel on Brian DePalma's Carlito's Way: "A wonderful effects film with a grand shootout in Grand Central Terminal. Sound editors love violence and noise." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

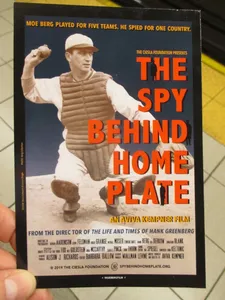

When I met with Aviva Kempner, the director of The Spy Behind Home Plate, at Soundtracks F/T, where she and Martin Scorsese mainstay re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman (The King Of Comedy, After Hours, The Color Of Money, The Last Temptation Of Christ, Goodfellas, Cape Fear, The Age Of Innocence, Casino, Kundun, My Voyage To Italy, Bringing Out The Dead, Gangs Of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, Shine A Light, Shutter Island, George Harrison: Living In The Material World, Hugo, The Wolf Of Wall Street) were putting in the final touches on her documentary, I had the chance to borrow her sound editor Ira Spiegel (Ken Burns's longtime collaborator) for a short while to clue me in on his work in creating the velvety flow of the picture.

|

| Ira Spiegel with Aviva Kempner while re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman works on The Spy Behind Home Plate. Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan and Carroll Ballard's The Black Stallion, executive produced by Francis Ford Coppola, are two of the films that Ira Spiegel talked to me about in admiration for the high quality in sound editing and sound design respectively.

In the rough cut that I watched of Aviva Kempner's extensive documentary The Spy Behind Home Plate, she catches a fascinating man of mystery, Moe Berg, baseball player, scholar, and World War II spy.

Anne-Katrin Titze: You have been working with Aviva [Kempner] before the Moe Berg film, right? In what capacity?

Ira Spiegel: I've worked with Aviva I think since her first film. I am a sound designer or sound editor and I prepare all the sound for the mix.

AKT: What were some of the special demands for this one?

IS: The quantity. Aviva's films are very straightforward. She wants to hear everything that she sees. And a film like this is entirely archival and it's just been a lot of work, the quantity has been really overwhelming.

In the archival footage we saw the people in the little shtetls in Europe, and the baseball games and it's a real joy for me putting in all the little details. It's almost like a watchmaker, working on the little details. That's sound editing, say, as opposed to sound design. This has been a great challenge in terms of sound editing.

|

| Ira Spiegel: "My job is to keep you immersed in the film and not to do anything that would distract you." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: How much does the time of the footage enter into your process?

IS: That's very critical. You can't be seeing footage like from the Twenties.

AKT: And have contemporary footsteps?

IS: Modern sounds, exactly. Early on, there's some footage of some little children playing in a field. I needed to effect the children and they're laughing and yelling. But I chose sound effects that are from the twenties. Just like when Tom [Fleischman] was cleaning up some of the old optic, I actually used old optical sound because I wanted it to fit with the footage, to feel natural. There's that quality.

AKT: What I liked about the film was that it felt almost timeless. There's a beautiful flow to it and it makes it feel one piece. And that although she is showing interviews from all different periods. The archival footage is all over the place and there are film clips that span from Alan Ladd to 21st century movies.

IS: That's really the art or the craft. If the filmmaker can have you enter into the world of the film without any interruptions and without you being distracted then they are successful. It's good to hear that. That you felt that. My job is to keep you immersed in the film and not to do anything that would distract you and say "What is that?"

Just choosing the sound effects is always … It's hard to describe how. I preview, like, I'll throw something in - it's almost like painting. If I don't like it, I'll put something over it. And I always leave stuff that I don't like. I leave it in, so that I can understand, you know, my reasoning. I leave it in but I make it mute so you can't hear it. So when I look at my soundtracks I can see the trail of my thinking.

AKT: That's fascinating - the muted sound process.

IS: Have you ever heard of the Harrison prize? This was in England. The first clock that could operate on a boat. Because a boat rocked. A guy named Harrison, John Harrison, created the first watch that could continue without a pendulum. That could operate so they could tell longitude.

And I think there was a man named [Lieutenant Commander Rupert T] Gould in 1917 or something, he tried to put the H2, the Harrison clock, back together again. And there were all these faults as Harrison had gone to make it. He started with this and then it didn't work and then he did this. So for me doing sound, leaving all the false trails helps me when I come back and review.

AKT: As you were saying earlier inside the studio, you are trying not to draw too much attention to what you put in. When the music comes in and the mixing part - there is a different idea at play where sound is trying to grab you.

IS: But it all has to work in concert. None of it should draw you out of the film. You need to feel in a sense like the film is communicating directly to you. Like a good novel. Don't you agree, that when you read a good novel you feel that it's been written for you?

AKT: Right.

IS: That's the feeling that we try to achieve. That the individual experiences really a comfort level, a flow, a joy.

AKT: I said to Aviva earlier, the song Night and Day that she was using temporarily for the version I saw, it cuts off right before Fred Astaire would begin to sing. I was waiting for Fred Astaire to sing because I recognised that particular recording. These are the dangers, too - that you don't want people to anticipate.

IS: I know she's had difficulties getting the rights to stuff, so Barbara [Ballow], the editor, has worked for a year on some things and then we had to change things.

|

| Spy cat at Soundtrack F/T in New York Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: Doing the sound, you must learn a lot about the subject matters?

IS: Every time I work on a film I do.

AKT: What are some of your other films?

IS: I've done all of Ken Burns's films.

AKT: All of them?

IS: Yes, since the beginning. And his brother Rick's. Both of them make these long-form documentaries. And with a lot of other documentarians in New York. And feature films, too. You know, for a sound editor, action - that's exciting to do. The film may be really not of a high quality, like an action film I've worked on. You know who Chuck Norris was?

AKT: Yes.

IS: There's a lot of shooting and banging and killing. They're very exciting to work on. Carlito's Way was a wonderful effects film with a grand shootout in Grand Central Terminal. Sound editors love violence and noise.

AKT: Are there films that you particularly love, that are for you at the top of sound editing?

IS: Of course.

AKT: Which would be for you the sound editing best of the best?

IS: In terms of sound editing, maybe Saving Private Ryan. In terms of sound editing, in terms of the quantity, it's extraordinary that you see so many things and hear so many things. How can you hear like a bomb go off and at the same moment you hear a footstep? It's remarkable. There's quantity and quality that sound editing which reached I think to me such a height.

And sound design, there are so many, but The Black Stallion, which was made before digital, it was made in 1979, Coppola produced it. It's a children's book. That has beautiful sound design and simple. Where it's not the quantity. It's just the heart-wrenching depth of just one sound effect, in my opinion.

AKT: Are animal sounds a big source?

IS: In The Black Stallion, he uses slowed down animal sounds, which we then hear later in the film, when the horse is suffering. There's a scene at the beginning of the film where the boat sinks. I can only hear the film, I'd love to look at the tracks, but it sounded like he had used horse moaning as the boat was sinking and he blended it with the sound of the horns. The disaster horn, the deep mmmmmmmmhhh.

AKT: I'm shivering.

IS: It was uncanny.

AKT: There are no animals in Moe Berg?

IS: No, but as sound editors we always use animal sounds.

AKT: How so?

IS: Like if a door opens and I need a squeak, sometimes I'll use a cat meow, just slowed down a little bit. So you get [he makes the sound]. For gunshots, I've used the sound of a body falling at the same time as the gunshot to give it a base-y sound. Even on magnetic we could slow machines down and reverb and make and explore.

This digital age has made it so much more immediate and gave so many more varieties. That's the sound design. There hasn't been much sound design in this, although sometimes I can't help myself.

AKT: For example?

IS: Well, near the end of the film [The Spy Behind Home Plate] when the atomic bomb is dropped and you see the devastation of Hiroshima, I have put in the distance, the sound of a whale crying underwater. So I added a little reverb and pitched it so it's in the same pitch as the music.

|

| Grand Central Terminal in New York was a location in Carlito's Way Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

And then I added a very mournful wind and the combination of the two - it just seems like wind in a completely devastated city. Again, it doesn't draw your attention to it. It's kind of like whaling, crying and wind married together. That's sound design. There's no rhyme, there's no rules as to how to do it. Editors just do their own thing.

AKT: Do you sometimes get sound ideas just walking down the street?

IS: I used to. Not anymore. I think I'm full.

Coming up - Aviva Kempner on The Spy Behind Home Plate.

The Spy Behind Home Plate opens in the US on May 24.