In the final installment of my conversation with Rebecca Miller on her documentary Arthur Miller: Writer we discuss family, wisdom and why "tragedy is more optimistic than comedy" for her and her father. Plays according to Arthur Miller are never finished but abandoned as you get nearer to the hidden meaning. It is really all about "approaching the unwritten, the unspoken and the unspeakable. The closer you get the more [there is] life to it."

|

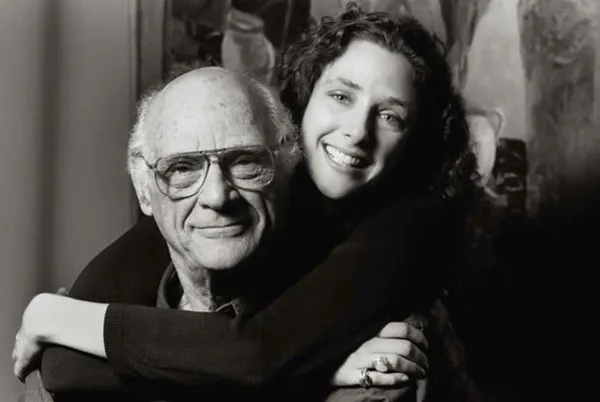

| Rebecca Miller on Arthur Miller's Timebends: A Life: "That's a wonderful book and I hope people will go back to that book." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

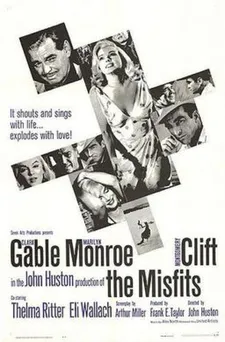

In 2017, Rebecca Miller appeared in Noah Baumbach's The Meyerowitz Stories (New And Selected) with Dustin Hoffman, who starred in Volker Schlöndorff's 1985 film adaptation of Death Of A Salesman. In Arthur Miller: Writer (a Spotlight on Documentary highlight of the 55th New York Film Festival) it is fascinating to hear the playwright recount the audience's reactions to the Broadway premiere on February 10, 1949 of Death Of A Salesman, directed by Elia Kazan and starring Lee J Cobb. No applause at the first performance. Silence. People weeping. Until someone started applauding and then "there was no end to it." He continues "Fathers cried all night. They felt nailed - 'It's me!'" The play where "the real becomes fantastic and vice versa," according to Tony Kushner, has a "film structure, a damaged memory structure."

Anne-Katrin Titze: When you go back to your father's childhood, it's very funny when you ask the siblings - so who do you think was your mother's favourite? And you get two answering: Oh, I think I was!

Rebecca Miller: It's classic, isn't it?

AKT: It says so much about the mother and about them.

RM: I love that the older brother [Kermit], who just knows these two artists [his siblings Arthur and Joan] who have their egos. And then Kermit who really didn't need to be a favourite. He's like, whatever.

AKT: I loved the story your father is telling about faking a limp [!?!] in order to not have to go to school. And then his mother [Gussie] took him to have oysters instead? Is that what he says?

RM: Yes! She was saying: "Oh, you can't go to school, you're limping. Let's go and have oysters!" Like, the two of them! You know, both knowing that this was a complete … Yeah, I think he had a tremendous sense of complicity with her.

|

| Rebecca Miller on her father's relationship with his mother Gussie: "I think he had a tremendous sense of complicity with her." |

AKT: Did you ever fake a limp?

RM: I remember having a little bit of … occasionally my mother would see … I've even done it with my own kids. Where they were like, "I don't feel well." You know that they just don't want to go to school. Sometimes that's enough reason not to go to school. But I think he [Arthur] felt a real kinship with his mother for a lot of different reasons. As I say in the movie, her dynamism and her talent and her frustration, I think, all played a big role in creating him.

AKT: It's a point where history, world history, comes together with the very personal.

RM: Exactly.

AKT: 1929 - the Wall Street Crash ends up in the bedroom.

RM: Exactly, I think that's one of the most important points that I was happy to make with the film, is that way in which economics and social - our world is inside of us. I think sometimes we forget that as a culture. We psychologise ourselves so much and individualise ourselves so much that we think of ourselves as our own problems. And the things that your parents did to you and all this stuff. Forgetting that you're really part of a larger system.

|

| Arthur Miller with Reverend William Sloane Coffin and Steve Minot at a 1968 anti-Vietnam War rally in New Haven, Connecticut |

AKT: Right. This is where your father's plays come in so strongly. To remind us that we are political beings. I mean, powers want us to believe that it's all our individual fault, that it's all our own psychology instead of seeing another picture.

RM: That's true, I think. It is one of the things at the end of the film - that we're all connected.

AKT: Another one of the wisdoms comes with a point he makes about Elia Kazan. Something we need to be reminded of. Kazan was made the villain, whereas McCarthy is the real villain and Kazan is actually a victim and why we focus on that. It's such an important reminder.

RM: I think it's a really important point. And he always said that. He was very distressed by the way that Kazan had been so villainised by the whole situation. I think he really understood his plight, you know.

AKT: Claude Lanzmann's Four Sisters - four portraits of women, interviews from the Seventies that did not make it into Shoah - makes a similar point. The same as Lanzmann did with The Last Of The Unjust and Benjamin Murmelstein: Point your outrage at the real villains! One of the women was a policewoman in the Lodz ghetto. Victims feeling they have to legitimise what they did. You cannot judge them the same way as the Nazis.

|

| Rebecca Miller on the death of her mother Inge Morath: "I mean, she was 79 years old. But people perceived her as a young woman." Photo: Dennis Stock |

RM: She was a civilian? A Jew?

AKT: Yes, she was. Living in the ghetto with her family.

RM: I see.

AKT: "Tragedy is more optimistic than comedy," your father says. Do you agree with him?

RM: I do. From his point of view, which is that in the classic sense a tragedy where somebody is willing to go to the end of their life for something that they believe in. Or that they're obsessed with in some way. There's something where you're asking the viewer to participate wholly.

And that action of going that far with the character will help them strengthen them in their own lives because it's so deep. Where comedy is more pleasurable in the moment, perhaps, - and can be very profound as well - but very often comes from depression. Very often comics are very sad people.

AKT: Yes, true.

RM: I mean, I myself have been doing comedies recently. It doesn't mean that I'm more optimistic. It's just … well, I don't know in my case. I'm just saying that in a sense, my saddest films were early on. I think, in a time where unhappiness was less real to me, and tragedy was less real to me than it is now. So I think, in a certain sense, tragedy may be the young man's sport. In the movie, one of the most interesting things to me is seeing the layers of personality accrue.

|

| John Malkovich and Dustin Hoffman in Volker Schlöndorff's film Death Of A Salesman |

You know, you see him in the beginning and he does that thing with his hand - it's like the writer, this is the world the world sees and this is the truth. And the writer when he is lucky, he can reveal. By the time he is older, he is not making the claim to be able to reveal truth. It's more like he is just bemused by human beings and all his certainty, I would say, is gone. It's like it's a different person almost.

AKT: It's interesting that you say that. I didn't get that from seeing the film. It folds so beautifully into itself.

RM: It's when you look at the early interviews and you see also that he hadn't been really burnt yet, by life.

AKT: The Touching The Flame chapter is titled well because it combines the McCarthy era and Marilyn Monroe. Two flames.

RM: Right, right, exactly. And go just a little too close.

AKT: You cut you father's hair!

RM: Yes.

AKT: Only that once or was that a regular occurrence?

RM: No, no, no. I did such a bad job. I love the scene because I thought it showed a lot about him. He didn't really have any vanity at that point in his life.

|

| Marilyn Monroe's great attraction, Arthur Miller says, was "her honesty," that she was "utterly without guile." |

AKT: He seems really trusting. I don't know how good you are with scissors…

RM: You see from the reaction of my friend Barbara there that I wasn't very good.

AKT: His first wife, Mary Slattery, is she a relative of the actor, John Slattery?

RM: I don't think so.

AKT: About Mary and their relationship, your father says in an early TV interview something along the lines of - she wanted a Jewish, intellectual playwright and "I wanted America."

RM: Yes, he said: "She wanted the intellectual, the Jew, the writer, the artist. I wanted America." Meaning, he was a boy who had grown up in Brooklyn and really knew a certain rather narrow strata of people. And she was from the heartland. She was from the middle of the country.

So when he got to know her mother, her family, that's where then All My Sons came from. I think that was in a way his passport, his ticket into a part of the country that he didn't know. It was really important, I think, because he as a writer had a broader ambition than to be just his own ethnicity.

AKT: The Timebends: A Life readings, were they done for you or did they exist for the audio book?

RM: No, they existed. That's a wonderful book and I hope people will go back to that book. It makes a lot of subtle kind of observations that one can't do on film, because you just can't.

AKT: I very much liked the chapter in the film about the reactions to Death Of A Salesman. How he describes opening night - silence, the applause, tears, and how everybody identified. How the play hit right to the heart.

|

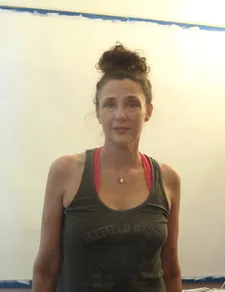

| Arthur Miller: Writer poster |

RM: It's a big part of the structure of the film because in a sense it is a classic structure both for the father and then for him. Because the father really goes from being the illiterate poor child to having built this big business and then he loses everything. And Arthur goes from being this poor kid to gradually rising up to a point where he has this huge enormous success. And then, as we say, he touches the flame, and inevitably there's some kind of fall.

AKT: What exactly was his father's business?

RM: He made coats.

AKT: Women's coats? From cloth?

RM: Yeah, wool coats.

AKT: Were there any left?

RM: No, I never saw any of those. It's been so long. He died, I think, before I was born or right when I was born. Like the coats already were twenty years behind. He hadn't had a business for many years, for 30 years.

AKT: I am fascinated by the legacy of cloth and clothes making in families. I talked with Gay Talese a few times about his father and the tailoring legacy.

RM: Oh yeah. That was such a big thing, right?

AKT: Somehow that family thing and the connection to cloth …

RM: Yes, I remember, apparently my grandfather … My mother had lovely clothes from her Paris days and he would look at the cut of the cloth and he would touch the cloth. He was still always a great appreciator of beautiful clothes.

AKT: What comes across as a big regret is the interview about your brother [Daniel] that your father promised you and that somehow never happened.

|

| Lee J Cobb and Mildred Dunnock in Elia Kazan's production of Death Of A Salesman |

RM: Yeah.

AKT: Because you were hesitant, too?

RM: Well, I mean, I don't think anybody can second guess unconsciously why things happen. But I do think that everybody has things they wish they asked their parents.

AKT: On film, you have him say "I will tell you about this."

RM: And then it didn't happen. I don't know. I don't really have an answer for that one.

AKT: You definitely wanted to include this in your film?

RM: I knew I had to address it somewhere and I did. I think we did what there is of the truth to tell, you know. Even with an interview, I'm not sure how much we would have learned.

AKT: Your mother "died as a young woman" is a sentence that made great sense to me.

RM: It's very true and I remember he [Arthur] said it. Because when people would express their grief and also their surprise that she died, you know, they were all so stunned that she died. She was somebody that seemed like she was just going to keep going, because she had so much dynamism and so much effervescence.

She was effervescent. She did have a young, very young quality to her. People felt sort of ripped off that she died. I mean, she was 79 years old. But people perceived her as a young woman.

AKT: Some people don't age the way others do.

|

| A clip from The Misfits shows an exhausted John Huston and we hear Clark Gable say the same lines to Marilyn that Arthur Miller had said to her in real life. She is the saddest girl they ever met. |

RM: Yes, in their spirit.

AKT: My grandmother who died at 98. And the feeling deep-down was - How could that happen? She was such a young woman!

RM: Yeah, yeah - always.

AKT: Just one more thing about the ending of your film. "Approaching the unwritten, the unspoken and the unspeakable."

RM: Yes, that's in the last interview.

AKT: Is that what you do too? What you want?

RM: I think one would hope that there's moments that you maybe penetrate into that. It's like it's the ultimate hope that you got a glimpse of that. And as he says, the closer you get to it, the more life there seems to be. It's very interesting, that last interview has actually really surprised me.

For somebody who is always thought of as really a realist, which in some ways he is. He's not a naturalist, though. But anyway, for somebody who is thought of that way, it kind of reveals a mystical component in his work and of the way that he sees making art.

AKT: Tying back also to his mother?

RM: Yeah, which I thought was really interesting. I think he was very private about all that part of himself.

AKT: Even to you?

RM: I think he had very mixed feelings about organized religion. He felt that organised religion had really done a lot of damage to human beings because there was so much violence done in the name of religion. I think the part of him that was connected to a spiritual component was really very very private. His own thing that existed in some of his work, like it's there but it's just that he didn't talk about it.

Read what Rebecca Miller had to say on her father and going inside the process of Arthur Miller: Writer.

Read what Rebecca Miller had to say on her role in Noah Baumbach's The Meyerowitz Stories (New And Selected).

Arthur Miller: Writer premieres on HBO March 19.