_600.webp) |

| Alena Lodkina: 'I think the night scenes are important because they evoke this hidden, half-sense of being lost' |

|

| Alena Lodkina: 'I think the eastern European sensibility is probably ingrained in me, because I grew up with Russian cinema' |

Alena Lodkina’s Strange Colours is one of the three films to emerge from Venice Film Festival’s Biennale College this year, an initiative that helps filmmakers fund and develop their work. Set in an opal mining community in the Australian Outback, it tells the story of young woman Milena (Kate Cheel) and her attempts to reconnect with her estranged father (Daniel P Jones), while also striking up a friendship with younger miner Frank (Justin Courtin).

Although scripted – Lodkina wrote the story with Isaac Wall – the film has a strong documentary flavour, with the supporting cast made up by members of the Lightning Ridge community in New South Wales and the landscape of the area also playing a large part. “This film started off as a documentary,” says Lodkina. “I made a documentary called Lightning Ridge: The Land Of Black Opals that screened at a couple of festivals last year. Some of that footage is used as little excerpts in Strange Colours, so that essayistic, almost anthropological study of the place always informed the narrative of this film. I was very much interested in this hybrid docufiction kind of film that’s coming out now.

“We had a panel with some film critics yesterday and David Bordwell, the film historian, made a comment that this film reminded him of Italian neo-realist studies, using non-actors and blending documentary and fiction. It was an acute observation, because a film that inspired me in a lot of ways was Stromboli by Roberto Rossellini. He kind of did a similar thing in dropping Ingrid Bergman into this place and the narrative kind of bends to the place and gives way to the characters and observational moments. So, I’m inspired by that and the feeling of reality and trying to reach towards a connection with people is something that a small budget film can provide. An intimacy, which is probably what people see in documentary films.”

Lodkina describes Milena as “a portal” into the landscape, as the audience are informed about the community through her eyes. The idea of coming somewhere that is new and, potentially, alien, is something familiar to the Russian-born director from her own life, as she now lives and works in Melbourne.

“You can’t escape who you are,” she says. “So I think the eastern European sensibility is probably ingrained in me, because I grew up with Russian cinema. Andrei Tarkovsky was my first favourite director, until I read that he didn’t think that women could direct films, which really broke my heart, although I still love his films, of course. So, I think that’s just intuitively how I see things.

_225.webp) |

| Alena Lodkina: 'It’s quite important to me that you have space so that you can be an observer' |

“Something my mum was saying was that the film has – because of its wide shots – a sense of distance and perspective. It’s possibly more removed than most films coming from Australia and I think maybe some people wouldn’t like that because it feels a bit distant. But it’s quite important to me that you have space so that you can be an observer. There’s a sense of mystery and no sense of easy access into this world for the audience.”

She says that building the relationships with the men who form the supporting cast has also made her protective of that world. “They have these intense lives, a lot of them and intense pasts and I didn’t want to expose that.

“I wanted the viewer to have a little sense of remove so that they could have a more critical kind of understanding of this word and think more about the more philosophical and existential themes as opposed to just being on a journey that just ends. I wanted to give perspective.”

Her perspective might be considered unusual more generally, as not only does she bring her own migrant experience to the film, she is also a female director scrutinising a community composed almost exclusively of men – we’re much more used to male directors telling women’s stories than the other way around.

“I guess it relates to the previous question of being an outsider and being a migrant and being a woman,” says Lodkina. “It creates a particular perspective. I like to imagine that it allowed me to have compassion and humanity. I didn’t want to present stereotypes of masculinity – like heroic masculinity or the ‘bad’ man. I didn’t want those easy kinds of characters. I wanted the film to have a feminine feel, if you like, slow and lingering. What is masculine and feminine? I guess, that’s kind of how we use those words. It’s got this romantic feel to it and that was, to me, my feminine eye.

“These guys are so real. They have the aesthetics of rough guys from the Wild West but that’s just the aesthetic sensation, they have very complex, rich lives.”

Lodkina says process of working with the community was also complex.

She adds: “Outside of the three main characters, everyone else is people in the community. We wrote all the parts for specific people – I knew them all and what their sense of humour was and what they believed in and felt about the place, so I knew there would be a good choir of side characters.

“The guy, Rat, who is the one who appears the most consistently, you see him polishing stone in the film, he is a very charismatic guy. He’s a bit of a drama queen and he was the hardest to get on board. I came to him early and pitched the idea of the film and he acted non-committal and cool but I could see he was really thrilled and that it meant a lot to him. And when we got him, the word got around town and other people said, ‘He’s doing it, so I’ll do it.’ So it was kind of like a chain and they were amazing to work with.

_225.webp) |

| Kate Cheel and Daniel P Jones as Milena and Max in Strange Colours |

The conditions of the Outback also presented technical challenges, not least in terms of the heat and the chances of running across brown snakes – the second deadliest in the world – while out on set.

“I was very lucky to work with cinematographer Michael Latham who is very meticulous about his lighting,” Lodkina says. “As you can imagine, it’s a very challenging landscape. In the Australian Outback the light is so intense. We had a generator but there’s only so much we could do. He concocted these immaculate set-ups for all the night scenes, in particular. I think the night scenes are important because they evoke this hidden, half-sense of being lost and not really being able to see everything – it’s such a big theme in the film, that kind of longing and being lost.”

Music also plays a key role in the film and was developed with composer Mikey Young, who is known for playing in post-punk band Total Control. “We hit it off right away,” says Lodkina. “He saw a rough cut of the film and really connected to it. He approached it with such intelligence. It was such a thrilling process to hear these sounds take shape. Right at the end, he came up with those sparse, kind of whistling sounds. They reminded me of Picnic At Hanging Rock, the sort of Western, mystery vibe and I fell in love with those tracks.”

Away from the film itself, Lodkina describes the Biennale College process as “remarkable”.

|

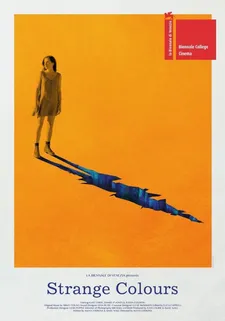

| Strange Colours - poster |

Strange Colours deserves all the interest it is receiving, look out for it to make an impact on the festival circuit as the year progresses. It is available to watch on Festival Scope's Sala Web until September 19.