|

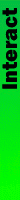

| Valeria and her cow Păuna and dog Duracell. Matthäus Wörle: 'After a few days, she felt that she could do whatever, whatever she wanted' |

The film had its world premiere at Thessaloniki International Documentary Film Festival, where we caught up with him to talk about his approach.

You first dealt with the village in your short Geamăna - did you always intend to make a longer version or was that something which grew from making the short?

MW: I was studying at the University of Television and Film in Munich. And I had to make four films in my studies. In 2020, I started to research my third film. I wanted to do a film about environmental issues or things like nature or pollution. And I found Geamăna. So I started in January 2020 with the research and then I continued because of Covid. In July, I was there for the first time and I met Valeria and we had a week together and then I went back to Germany to sign the contract with my university to be able to shoot there. And two days after that, I shot my short film for seven days. But before I started shooting, I knew that this topic was interesting for me, but I was not sure if Valeria is up to such a long shoot.

|

| Matthäus Wörle: 'It is like it is like falling in love. Sometimes when you find a topic, you just feel it that it's right that you can work on that for like four years' |

How long did you shoot for the second time?

MW: We had the first shooting period in September 2021, because we had to wait for some funding money. And then we got back there in November 2021, in January 2022 and in August 2022. So I was in the editing room for one and a half years. It was quite a long time.

Valeria obviously liked you. I guess she perhaps liked someone about the place because she was there on her own with her dog and her cow, so having human company was quite pleasant, I imagine.

MW: Of course, it was like that. Her family were coming to her every week or every other week because they needed to bring him some water at least because she had no running water there. But of course, she liked our company. And as I said in the beginning, it was not such a hard time for her when we filmed her, because I never told her, “Can you do that?”, “Can you do that again?”, “Sorry, we need a closer shot for that” or anything like that. After a few days, she felt that she could do whatever, whatever she wanted. I asked her what she was up to for the day? And then she said, “Okay, I'm going to the cow. I'm bringing something there. I'm making some cheese and cooking. Do you want something?’’ It was very, very important for me to let her feel that she can do whatever she wants. And if she wants to rest, and if she wants to have some time, she said that to us, that was not a problem. And as you can see, in the firm, we had a lot of shooting as well without Valeria to understand this place. And, of course, we had to talk to a lot of people from the whole area.

You shoot it in a very observational way but you're using quite a bit of voiceover from Valeria that's obviously from an interview situation. Did you do the interview upfront? Or were you just interviewing her periodically as you were shooting the film?

MW: We did that periodically. I did an interview for the short film as well, or two interviews. And that is the only thing that I used for the long film as well. Some parts of this interview, but no footage that we shot back then. So they are two different films about the same topic. But yes, we did seven or eight interviews in total. In every shooting period, I asked her when she had time for that. We always did that in her house and after that at her son's house. It was very important for me to let her express everything she felt and what she was going through and it was very important for us as well to see how she changes in her voice. She cried a lot in the end and that is what you can feel also in the film.

AW: You do get that real sense of loss. It's so brutal that they literally deconstruct her house, which maybe people probably are not expecting.

MW:To be honest, it was a good thing that the house was taken away. Because there is a tradition in Romania that the men when they are 16, or something like that, they, cut some trees, and they bring them in shape for a possible house and a possible wife they will get married to. So her husband brought these trees into their marriage, and they built the house together. And that is a traditional way to build the houses. So they don't use any steel, it’s just the wood fitting inside each other. So it is interesting for people today as well, because it is traditional, and there are not so many houses left that are built like that. They told me there is just one man over 80 who can number the word to say, “Okay, we bring that away, and then I can bring it back together.” So yeah, the house is somewhere new in Romania because they sold it to someone. That is something that helped her feel a bit better.

When it comes to the information about the Ceaușescu era and the copper mine that is causing the problems, was that something you already knew about or that you found through research. It’s interesting because it’s an observational film but you also include this propaganda material.

MW: There are two reasons why I did that. In the beginning, it was very important for me to ask myself, why am I allowed to tell a story about an old Romanian woman in the mountains? And at least there is no answer to that, especially when you're making documentaries, you have to ask that every time. And when I'm asking myself if I'm able to, then I found the answer for myself is that I have to research a lot, I did talk with Valeria, not so much about communism and the situation back then, of course, about her personal but not the political situation. But it was very, very important for me that she understood that I know a lot about her political background and the background of Romania. We are not discussing that but she understands that I'm really interested and I really know about Romania, and I really know about politics back then. And that is just something you have to do sometimes for your films, to understand the people there a bit better, because you cannot go there just to take her story and go away. Too many people are doing that in my opinion.

|

| Matthäus Wörle: 'It was very important for me to let her express everything she felt and what she was going through' |

I wanted to include this part [about those who want the mine] in the film. But I realised that it is not possible that someone will talk to me in front of the camera about the good things about the mine or that they are working there. I tried to make that happen a lot, to be honest.

AW: That speaks to the complexity of the situation that people don’t want to voice an opinion on it. Did Valeria ever get to see the film?

MW: She saw the short film but she was not really interested in the result. It was not important for her to see herself on a big stage or anything like that. She liked it but she did not say a lot about the film.

You’ve said you were interested in films that sort of had a bit more of an environmental theme to them? Is that something that you think you're going to do more of in the future?

MW: It was something that I wanted to do at least once because it is very important for me - climate change topics and nature and pollution - environmental topics are very important for all of us. But I wanted to make an observational film, and not an activist film. Don't get me wrong, I think that it's very important, in many ways, that there are activists, and in my free time, I am sometimes an activist as well. And I'm a totally political person. You know, I have so many points of view about so many political topics going around in the world. So that's very important for me. But in a way of storytelling, as I said, it is too easy for me to say, “This is right, this is wrong”. And I am the one who tells you that is the route. I'm just trying to get to it more in an emotional way.

It is like falling in love. Sometimes when you find a topic, you just feel it that it's right that you can work on that for like four years because you need to, otherwise, if you're not interested one year after you started the project, it is not good for your project and it is not fair for your protagonist. So let's see. I'm starting on research but as you can imagine, I just finished my university a few weeks ago, and I’ll try to get some money first. I need to find someone who is paying for the research as well, because I did so many films in university without getting a penny. And it is important that if I want to do that as a job, I need to find ways to get money out of it.